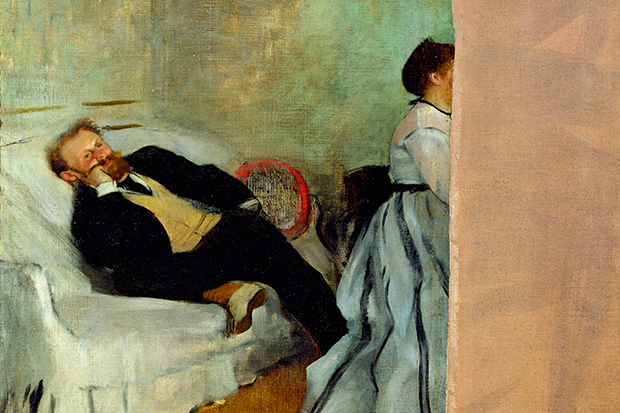

When the old curmudgeon Edgar Degas died in 1917, a stunning trove of works by Edouard Manet — eight paintings, 14 drawings and 60 prints — was discovered in his studio. There, too, was a portrait of Manet and his wife Suzanne, painted by Degas 50 years earlier. But its right-hand third was missing — which included half of Suzanne’s body and all of the piano she was playing. For some reason, Manet had put a knife through the canvas and sent Degas packing with what remained.

The duo’s relationship is one of four ‘friendly rivalries’ considered by the

Boston Globe art critic, Sebastian Smee, in his new book (Matisse vs Picasso, Pollock vs de Kooning and Bacon vs Freud being the others). In each case, Smee reckons, competition between the pair changed the course of modern art. And this wasn’t a matter of sworn enemies slugging it out for art-world supremacy, but of ‘yielding, intimacy and openness to influence’ inspiring the respective parties to greater heights.

Smee avoids chronological order, which is a pity, because with that we might have followed the influence of each pair on the succeeding one. He begins with Bacon and Freud, perhaps because theirs is the relationship he knows most about (his previous five books have all been on Freud). Or perhaps it’s because their relationship was the juiciest, with a hint of the sexual about it. Bacon’s one-time neighbour, the art critic David Sylvester, insisted that, for all Freud’s reputation as a ladies’ man, ‘Lucian clearly had a crush on Francis’.

The pair were 22 and 35 respectively when they met in 1945, and Smee steers us engagingly through the ensuing years, as Bacon — going from strength to strength — snapped British art out of its neo-romantic comfort zone into a new world scarred by the horrors of the second world war. The pair saw each other on an almost daily basis, and gradually a Bacon-inspired Freud — dispensing with his old sentimentality and revelling in the viscosity of oil paint — achieved a greatness of his own.

Smee is a gifted storyteller. This is clearest in the Picasso-Matisse chapter, as he ratchets up the tension before the pair’s fraught first meeting at the Spaniard’s studio in Montmartre in 1906; and also, later, as he jump-cuts headily between them, as Henri and Pablo create masterpiece after masterpiece across Paris from each other.

With so many paintings under consideration, it’s regrettable that just 14 are reproduced. A bigger problem, though, is that Smee’s wish for a compelling narrative comes, at times, at the expense of fact. I lost track of how often he makes claims he has no means of standing up. To give two examples: Matisse’s inner insecurity, in contrast to his outward urbanity, ‘was something that Picasso, preternaturally alert to weakness in others, must have grasped’. Meanwhile, leaving his native Holland for the US, inflated ‘within de Kooning a yearning for fellowship, for the camaraderie of… a pilgrim on the same hard path’. The would-be novelist in Smee regularly trumps the historian.

In each of the four relationships, there seems to have been a period of a few years of peak intensity — and in the case of Pollock and de Kooning, the end was hastened by the former’s death at the wheel of his car. (Pollock’s lover Ruth Kligman survived the crash and, within a year, became de Kooning’s girlfriend.)

I must admit I wasn’t aware that Pollock, the macho drunk from Wyoming, was Tennessee Williams’s inspiration for Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire. But, in the main, there’s not much in this book that’s new, which is perhaps unsurprising, at a mere 85 pages per face-off. Might Smee have been wiser to have focused on just one of his four duos and writing a joint biography? Possibly — but, to be fair, his whole point is to stress the similarity between the different rivalries.

One artist always seems to have been methodical and technically gifted, the other impulsive and instinctive; one artist tends to have been socially adept, the other rather reticent; one artist seems to have been senior while the other played catch-up… before the rubbing off on (and up against) each other began in earnest.

Parallels between the four relationships are striking, but you can’t help but feel Smee’s blanket approach is reductive. Artistic inspiration is notoriously tricky to pinpoint. What’s more, in this case we’re dealing with eight of the most brilliantly outlandish individuals in art history. They’re surely the last people whose behaviour and feats we should be trying to explain by way of a pattern.

Heaven only knows what prompted Manet to slash that picture of him by Degas — or, for that matter, why Degas decided to keep it.

The post Paintbrushes at the ready appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in