I wonder why ENO has invested in a new production of Berg’s Lulu, when the previous one, which we first saw in 2002 and then in 2005, was so brilliant as to be virtually definitive. (Of course, that last word is anathema to operatic ‘creative’ teams, for obvious reasons.) Not that this new one, directed by William Kentridge, isn’t good too, though it is excessively busy, compounding the hyperactivity of the score and action. It doesn’t do anything to clarify matters, though almost all the questions one is left asking are ones that the composer-librettist has set. The very full and useful notes in the programme trace the history of the Lulu plays and their transformation into the opera, in a way that makes clear what a mess it was how the whole thing slithered into being, both dramatically and, hardly separably, conceptually. What emerges with some degree of lucidity is that both Wedekind and Berg made artistic capital out of their highly ambivalent attitudes towards women and women’s sexuality, and hoped that by leaving their feelings unresolved and letting them coexist uneasily they would engender something that counted as a modern myth, and so make confusion seem deep and labyrinthine. It’s not a particularly high-risk strategy, since audiences are only too content to be baffled and impressed. But it is worth thinking about the difference between a dramatic experience that leads you into a problem and which enriches your life by having you constantly returning to it and using it as a reference point, and on the other hand an experience that leaves you bemused and, so to speak, standing on the outside and wondering what is going on within.

It seems clear to me that Lulu belongs to the second category. It is a work of enormous allure as well as repulsiveness, and one to which I have returned regularly over the five decades since I first saw it, fascinated. Its sound-world is all its own, almost always quite different from that of Wozzeck, a far greater work. The point of nearest contact is the supercharged orchestral interlude after Act One scene two, which rubs shoulders with the notorious

D minor interlude in Wozzeck after Wozzeck drowns. The world of the earlier opera is permeated with strong feelings, unironically expressed, so that that interlude can seem to render explicit what we have already grasped. By contrast, Lulu is so sharp and dry for most of the time that any chance for emotional abandon is gratefully taken. The relationship between the stage and the pit is a vertiginous one: on stage, people say and do things that are only intelligible if they are intensely overwrought, yet the reactions of other characters, especially Lulu, are offhand and often comically brutal. The same goes for the orchestra, which seems to be enjoying itself in self-sufficient musical ingenuities, alternating with passages of typically Bergian heavy breathing and compassion. Yet the music and the action are only sometimes coincident, and it’s hard to predict when. This allows for further intimations of perplexity and the abyss.

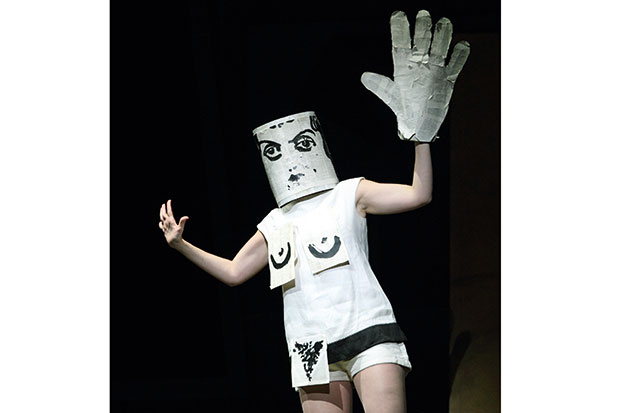

Kentridge and his team update the action to the 1920s, thus prolonging Jack the Ripper’s life by several decades. Projected cartoon images come and go at a vertiginous rate, and since almost all Lulu’s words are inaudible or unintelligible, the eyes are kept dizzyingly busy. Brenda Rae is Lulu, and in Act One on the first night at least she undersang, with only her top notes carrying. Lulu may be a blank on which the other characters, and the audience, can project their own image of womanhood, but she does at least need to be sexy. Rae has the figure but not the magnetism that leads to cardiac arrests, suicides and the other fates that await those who exploit and are exploited. The survivor, apart from Jack, is the malodorous Schigolch, well sung but hygienically acted by Willard White.

The most sympathetic figure, as usual, is the Countess Geschwitz of Sarah Connolly, her acting and singing equally moving. The rest of the amorous team are a distinguished group, many of them veterans. Mark Wigglesworth and the orchestra are tremendous, but even so I’m heretical enough to wish that Act Three had never been completed by Cerha, and to return to my older recordings, with the music from the Lulu Symphony, much briefer and at last giving permission for a straightforward response.

Independent Opera is giving four performances, the first in the UK, of Karl Amadeus Hartmann’s Simplicius Simplicissimus at the Lilian Baylis Studio. Hartmann was part of the ‘inner immigration’ of Germans hostile to the Nazi regime, but determined to stick it out. His idiom would not have given even the Nazis’ sensitive ears offence, but the opera, like the rambling novel on which it is based, is an indictment of war, hence the delay in its production. Simplicius is a young man, brilliantly performed in this production by Stephanie Corley, who encounters several archetypal figures and gets roughed up. Nearly everyone is dressed as a boy scout, and there is lots of running around and wrestling. It could just as well be staged as a cantata, in fact might make a greater impact that way.

The performance was excellent, the in-yer-face acoustics of the theatre giving it maximum impact, but that turned out to be pretty small, thanks to Hartmann’s generalised idiom, neither expressive nor illustrative, uniform in its depiction of whatever varying ordeals or consolations Simplicius encounters. Under the convincing baton of Timothy Redmond, and in David Pountney’s translation, one can’t imagine the work being better served, so it has only itself to blame.

The post Another fine mess appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in