Wexford is to opera-goers what casinos are to gamblers. The uncertainty, the hope, the exhilaration — they’re all a crucial part of a festival that annually rolls the dice, plucking three obscure, often all but unknown, operas from the repertoire and giving them a staging. Dealing the cards is David Agler, the artistic director whose canny choices ensure that not only the house but also the audience always wins. Add to the mix Wexford’s ear for an up-and-coming star (Juan Diego Flórez, Mirella Freni, Joseph Calleja and Daniela Barcellona have all made their mark here), and you can understand the festival’s uniquely addictive quality.

It’s somewhere between the Bacchanale, the appearance of Satan and the eruption of the volcano that kills the entire cast that it becomes clear that Félicien David’s Herculanum isn’t kidding around. You’d struggle to find anything grander than this particular grand opera — a four-act fantasy of scheming imperial seductresses and pious Christian martyrs. Here director Stephen Medcalf trades the Roman empire for empire-line fashions, relocating the action to Naples at the turn of the 19th century. It’s a transposition that makes little sense of the work’s religious conflict, but since that’s all just a ruse for a B-movie-style romp it hardly matters.

David’s 1859 opera is currently enjoying something of a renaissance thanks to a new performing edition and a superb recording from Hervé Niquet and the Brussels Philharmonic. But if this staging teaches us anything it’s that Herculanum is an epic that lives best in ear and imagination. The flimsy dramatic scaffolding supporting the opera’s weighty scenario can be ignored on disc in a way that it just can’t be on stage, allowing the focus to fall where it should — on the rich and surprisingly supple score.

Woodwind beckon and tease, flutes and oboes voicing the decadence of the court, whisking the listener into giddy dances and drinking songs. But they meet their match in the stern beauty of the Christians’ music. The unaccompanied hymn that opens Act Two has all the angular elegance of a Poulenc motet, while arias for both Lilia (the intermittently exciting Olga Busuioc) and Helios (promising young tenor Andrew Haji) cut cleanly through Olympia’s florid excesses. Nature, too, has a voice here. The volcano that boils ever more briskly between acts in Shadowlab’s videography overflows in a searing orchestral finale that stops the action in its tracks.

Jean-Luc Tingaud conducts a strong cast and the even stronger Wexford Festival Chorus, filling this small house with a sense of the opera’s ambitious scale. If the bright-toned Haji is the pick of the soloists, then Daniela Pini’s imperious Olympia comes a close second, negotiating the role’s extremes of register and style with disdainful ease.

But if Herculanum is a fascinating curiosity then Samuel Barber’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Vanessa is the real deal. Every year there’s one — an opera that sends you home an evangelist — and this delicate melodrama (a contradiction both Barber’s score and Menotti’s libretto manage to dissolve) deserves a bigger stage, preferably in one of the major UK opera houses.

Abandoned by her lover Anatol, Vanessa retreats from the world, waiting and hoping on her isolated estate with only her mother and niece for company. But when Anatol’s handsome young son arrives unexpectedly, breaking into this shuttered household of women, the aftershocks threaten to destroy them all. Poised somewhere between Chekhov and Ibsen, the opera’s violence is all the more potent for being repressed. Rage and hurt are sharpened to a stiletto point, thrust inwards by characters whose lives of drawing rooms and tea dances offer no other release or recourse.

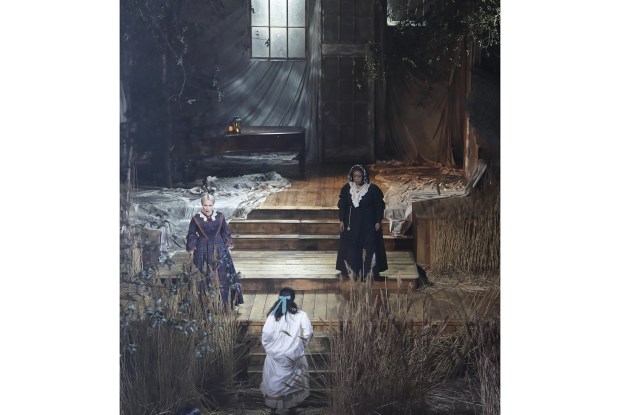

Faded into creams and greys – interiors with all the muted elegance of a Hammershoi painting, and something of that emotional charge, that air of expectancy — Cordelia Chisholm’s exquisite set places us postwar, possibly in East Coast America, possibly the anonymous ‘northern country’ of the original. Into this promising frame Rodula Gaitanou pours a production of dextrous subtlety that lives in the understated detail of its human observation. Rosalind Plowright’s Baroness strides with assurance but restless hands betray her uncertainty; the caddish Anatol (Michael Brandenburg) rushes out into the snow to save Erika, but not before pausing to don a coat and scarf.

Barber’s score balances constantly on the edge of song, tipping over occasionally (in Erika’s lovely ‘Must the winter come so soon?’ and the astonishing final quintet) but mostly caught in suspended melodic animation. There’s Strauss here and Mahler too, but the autumnal harmonic landscape is unmistakably Barber’s own — American-accented, but never coarsely so.

Conductor Timothy Myers gives the music space to breathe, never rushing the pace of this concise drama. He supports an ensemble cast led by Claire Rutter’s brittle, girlish Van

The post Buried treasure appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in