In 2011 the New York Times’s chief dance critic, Alastair Macaulay, asked:

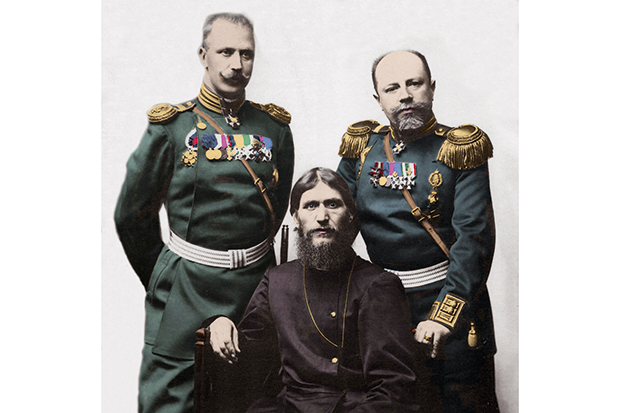

How should we react today to ‘Bojangles of Harlem’, the extended solo in the 1936 film Swing Time in which Fred Astaire, then at the height of his fame, wears blackface to evoke the African-American dancer Bill Robinson? No pat answer occurs.

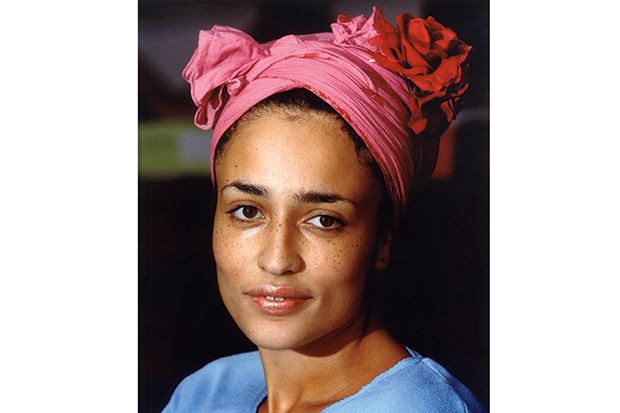

Zadie Smith’s fifth novel is a brilliant address to that question. In the prologue the unnamed narrator, who has recently lost her job as assistant to a Madonna-like star, goes to the Royal Festival Hall to hear an Australian director ‘in conversation’ and sees a clip from Swing Time — ‘a film I know very well, I watched it over and over as a child’. She is bored and a bit confused by the discussion of ‘pure cinema’ as the ‘interplay of light and dark, expressed as a kind of rhythm, over time’. Later that evening, after sex, she shows her boyfriend the same clip on her laptop. He is shocked by Fred Astaire’s blackface and so is she: ‘I’d managed to block the childhood image from my memory: the rolling eyes, the white gloves, the Bojangles grin. I felt very stupid.’

The novel that follows is structured around the narrator’s childhood friendship with another girl from the same north London estate. Both were born in the mid-1970s, brown, and are obsessed with dancing. The narrator has a black mother and white father, while her friend Tracey has a white mother and a black, mostly absent, father. Aged about four, Tracey tells the narrator authoritatively that her family is ‘the wrong way round’:

‘With everyone else it’s the dad,’ she said, and because I knew this to be more or less accurate I could think of nothing more to say. ‘When your dad’s white it means —’ she continued, but at that moment Lily Bingham came and stood next to us and I never learnt what it meant when your dad was white.

Through deftly deployed period detail — the delicious Angel Delight that wasn’t real food; the peculiarly popular plastic doll that wet itself — Smith brings these late 1970s and early 1980s childhoods to life. One fireworks night, Tracey’s father, who is allegedly a backing dancer for Michael Jackson, bursts into the story and beats up Tracey’s mother. One winter afternoon, the narrator is suddenly introduced to her father’s white children from a previous marriage, one of them a trainee ballerina. Afterwards, the narrator and Tracey are closer in unspoken ways:

And now — as if we were both trying to get on a seesaw at the same time — neither of us pressed too hard, and a delicate equilibrium was allowed to persist. I could have my evil ballerina if she could have her backing dancer.

Smith is a kindly writer, deeply respectful of the ‘delicate equilibrium’ intrinsic to personal identity. Since her first novel, White Teeth (2000), she has been pursuing this subject. Most of us would find it hard to give a stable answer to the question: ‘Who are you really?’ The response depends so much on who is asking and why. The Hausa proverb that Smith takes as her epigraph here makes the same point: ‘When the music changes, so does the dance.’

The character with the most robust sense of self in Swing Time is the narrator’s mother. She has intellectual aspirations for herself and her daughter, believes her postman husband to be culpably lacking in ambition, and ends up as an autodidact MP. One of the most memorable scenes in the novel is the pottery lesson she gives her daughter and Tracey on the balcony:

It was a messy process, we probably would have been better off doing it in the bathroom or the kitchen, but the balcony allowed for an element of display: from up there my mother’s new concept in parenting could be seen by all. She was essentially asking the whole estate a question. What if we didn’t plonk our children in front of the telly each day to watch the cartoons and the soap operas? What if we gave them, instead, a lump of clay, and poured water over it, and showed them how to spin it round until a shape formed between their hands?

The ‘what if’ question is abruptly answered by Tracey, who decides that the shape between her hands resembles a brown penis and promptly collapses the whole social experiment into hilarity.

Tracey goes to stage school while the narrator takes a course in gender and media studies in southern England. Smith has always written candidly about sex:

I could not be a girl, nor could I be anybody’s baby, I could only be a female human, and the sex I understood was of the kind that occurs between friends and equals, bracketing conversations, like a shelf of books between bookends.

But despite this robust and healthy approach to intimacy, the narrator is frustrated with her boyfriend:

Why did he think it so important for me to know that Beethoven dedicated a sonata to a mulatto violinist, or that Shakespeare’s dark lady really was dark, or that Queen Victoria had deigned to raise a child of Africa, ‘bright as any white girl’? I did not want to rely on each European fact having its African shadow, as if without the scaffolding of the European fact everything African might turn to dust in my hands.

After she begins working for the Madonna-like star, whom she and Tracey idolised in childhood, the narrator visits Africa and participates in the foundation of the Illuminated Academy for Girls. On one of her trips she sees two barefoot girls walking hand in hand along the road, looking like best friends.

They waved at me and I waved back. There was nothing and no one around them, they were out on the edge of the world, or of the world I knew, and watching them, I realised it was very hard, almost impossible, for me to imagine what time felt like for them, out here.

Honest recognition of the limits of imagination is also important when the narrator visits a slavery museum, built in 1992 at one of the original trading posts. ‘Makes you want to cry, dunnit?’ says the mother of a British family. But the narrator doesn’t cry; she is distracted by the three-toothed mouth of the guide blocking out the light from the tiny cell window:

‘You will now feel the pain,’ he explained through the bars, ‘and you will need a minute alone. I will meet you outside after you have felt the pain.’

Smith’s determination to face the absurdity of this situation is poised and confident: the beggars outside the museum, the misery tourists, the ‘Welcome Centre’ and historic horror. Whatever the weight of the past, she refuses to give up on the present. The present is freedom — an opportunity to make amends and entertain.

Tracey’s life, as a bit-part chorus-line dancer, then a single mother back on the estate where they grew up, crisscrosses with the narrator’s life as an educated, childless international traveller. The friendship between them is fraught but unbreakable. Whereas Tracey, the more naturally talented dancer, rigidly separates black music from white, the narrator holds out hope that

there must be a world somewhere in which the two combined. In films and photographs I had seen white men sitting at their pianos as black girls stood by them, singing. Oh, I wanted to be like those girls!

Smith gives her narrator the gift of

song. At first, when she is young and shy, she sings deliberately underneath the volume of the piano, but gradually her confidence grows and her arresting original voice rings out. ‘Whatever I was feeling I was able to express very clearly, I could “put it over”.’

Ultimately the message put over in this graceful book is that entertainers are free: ‘To me a dancer was a man from nowhere, without parents or siblings, without a nation or people, without obligations of any kind.’ How should we react today to ‘Bojangles of Harlem’? The answer in Swing Time could not be clearer: the story is the price you pay for the rhythm.

The post When the music changes appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in