It is said that the case for freedom of expression needs to be restated in every generation, but things move faster in the digital era. Just three years after an attempt at state regulation of the press ended in ignominious failure, a fresh effort is being made. The government has begun a consultation on a plan to impose stiff financial penalties on newspapers who refuse to sign up to a state-approved regulator. Anyone wishing to give their opinion on such a regime has until 10 January.

It is odd, for a start, that Theresa May’s government feels the need to consult on whether it has a duty to uphold fundamental British liberties. A 300-year tradition of press freedom ought not to be abolished because people (quite understandably) had better things to do than to write in and explain the basics to ministers. But it seems the Prime Minister is calling for reinforcements. Twice, now, regulation to menace the press has been inserted in legislation in the House of Lords only to be narrowly defeated in the Commons.

Press freedom is, once again, hanging in the balance. For generations, politicians have been annoyed that their writ does not extend over newspapers. Now and again, they volunteer themselves as custodians of press freedom and architects of a new regulatory regime. David Cameron did so in the aftermath of the hacking scandal. Following the resulting Leveson inquiry, the government set out a royal charter for press regulators. No newspapers signed up to it. The question the government is now considering is whether to force them to do so.

The plan — called section 40, after a so-far-unused part of the 2013 Crime and Courts Act — would mean that if a libel action was brought against a newspaper, it would be forced to pay the legal costs of its opponents even if it won the case. It is not hard to see where this would lead. Rich and powerful people who had something to hide would be able to threaten newspapers into pulling stories they found inconvenient. The risk of huge legal costs would be used as a battering ram against truthful reporting. To MPs, still resentful of the expenses investigation, that sounds ideal.

If defendants found not guilty of fraud or theft were sent a bill for the Crown’s prosecution costs, as well as the police’s bill for investigating them, it isn’t hard to imagine how human rights groups would respond. Yet because this obvious system of injustice is aimed at the press, it has generated rather less protest from people who profess to be of liberal mind. Indeed, Labour and Liberal Democrat peers have been the most active in pushing for section 40 to come into force.

The only way to escape the penalty would be to sign up to a state-approved regulator. One is waiting: Impress, an appalling outfit funded by Max Mosley. He has been on a mission to suborn the press ever since details of an orgy he participated in found their way on to the front page of the News of the World. When that paper collapsed in the wake of the hacking scandal, Mosley scented blood and devoted significant chunks of his fortune to going after the press more generally — and financing those who support his vendetta. He recently gave £200,000 to the office of Tom Watson, now deputy leader of the Labour party.

No self-respecting title would submit to Max Mosley’s regulator, and yet the section 40 proposal would bankrupt newspapers who defy the state-backed system. It is not just showbusiness or celebrity reporters who face being driven out of business. Serious investigations into wrongdoing by corporations, politicians and officials face the chop, too. All this will be as much the Guardian’s problem as the Daily Mail’s; more so, in fact, as the former is a lot weaker financially. Local newspapers could be sunk by crooks, chancers or conmen.

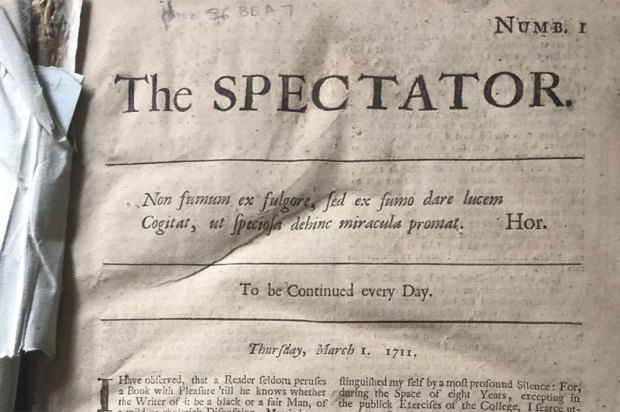

The Spectator was the first national publication to come out against the system of press regulation envisaged by Lord Leveson. Since we declared our position in 2012, every national newspaper has come to the same conclusion: not one will sign up with Max Mosley’s regulator. That includes the Guardian, whose investigative work did much to prompt the Leveson inquiry.

That should tell the government something: Leveson’s recommendations have already failed. When every single newspaper has decided that it would rather risk massive new libel costs than submit to a regulator sanctioned by the state, it is a sign of the depth of feeling on this matter across the press, from left to right.

Putting questions out to consultation is a standard response of ministers faced with awkward decisions. It feels democratic, yet many consultations simply generate masses of programmed responses from activist groups. The section 40 consultation is no different: for weeks Hacked Off has provided an electronic form to help its supporters bombard the Culture Secretary, Karen Bradley. She, the Prime Minister and her cabinet should have the courage to take a longer view and consign section 40 to the regulatory scrapheap.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in