The SA economy is stagnating or even declining. The Labor government has been in power since 2002, now led by a Left, ‘ideologically driven’ Premier. It has the highest energy prices in the country.

The SA economy is stagnating or even declining. The Labor government has been in power since 2002, now led by a Left, ‘ideologically driven’ Premier. It has the highest energy prices in the country.

Australia’s Chief Scientist reviewed the impact of the 28 September 2016 SA state-wide total blackout of electricity supply: he estimated the overall cost of the blackout at $367 million, and it would have been worse had it occurred earlier in the day. BHP Billiton’s Olympic Dam mine was without full power from 28 September to 13 October and this, together with another outage on 1 December, cost $100 million. BHP was not impressed by the Treasurer’s suggestion that it should have its own back up generator.

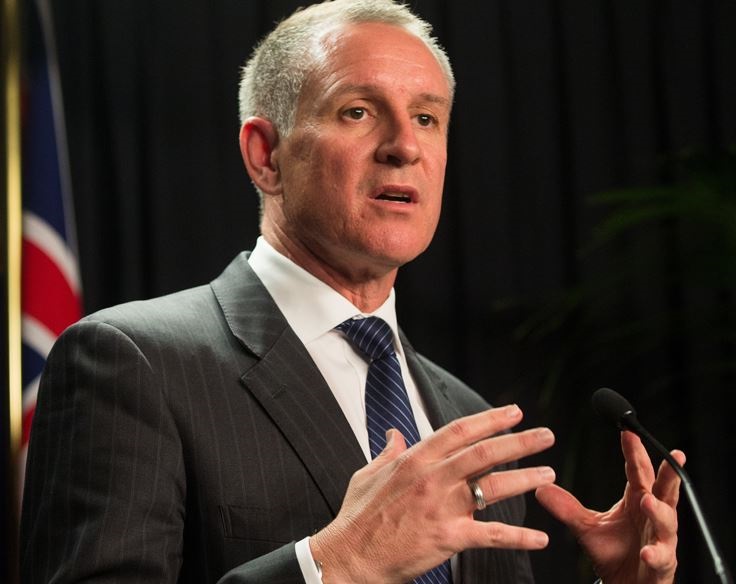

Jay Wetherill, Premier since 2011, has introduced, continued or intensified existing green left policies, notably in the electricity sector, creating the nation’s highest electricity prices. His government has tried to marry this with a commitment to economic growth, which has mostly failed.

How has this conjuncture occurred?

From 1938 until 1965, SA was run by the Liberal Country League (LCL) led by Sir Thomas Playford. He was a suburban fringe, small farmer, an orchardist, and successfully used the state instrumentalities to industrialize the state, with private investment, behind the tariff walls Menzies maintained. Metropolitan Adelaide grew quickly, together with a few other smaller industrial towns.

Playford maintained LCL political dominance by continuing a Constitutional rural over-representation in the lower house – Labor called it the ‘Playmander’ – and the usual property qualification for the Upper House. The LCL didn’t have so much of a popular organisational presence in Adelaide, and didn’t need it.

By the mid-1960s the defined metropolitan area spilled into the country for seat distribution purposes, and that system of gerrymander came to an end. In the city the industrialization process had produced a numerous industrial working class in the western and northern suburbs that was heavily unionized and voted Labor. Under fair boundaries Labor would win elections. In 1965 it did, then fought a near draw in 1968, but the LCL formed government.

Since 1936, the House of Assembly had comprised 39 seats – 13 in metropolitan Adelaide, and 26 in the country. The State constitution then required there be two country seats for every one in Adelaide. But by 1968, Adelaide accounted for two-thirds of the state’s population, 620,000 to 450,000. But the number of country members remained twice than that of the metropolitan areas.

In 1968 the LCL won only three metropolitan seats. However, Labor lost two country seats to the LCL, resulting in a hung parliament. The sole Independent delivered government to the LCL. The rural seat of Frome then had 4,500 voters, Enfield had 42,000 voters.

Steele Hall succeeded Playford as LCL Leader, then as Premier in 1968 and expanded the House of Assembly to 47 seats – 28 metropolitan and 19 rural seats. The reform made it very likely that Labor would win and, indeed, Labor won the 1970 election.

From 1970 onwards Labor won regularly and, at first, more easily as electorates became more equal under Labor’s further 1975 reforms. Don Dunstan was the first modern Labor leader – premier from 1967-8 and 1970-79 – under this system and became justifiably famous nationally for his social reform agenda. His interest in economic development was less substantial and the structure of protected industry was broadly maintained. In 1979, embroiled in scandals, he fell ill and was replaced by his deputy, Des Corcoran, who lost the 1979 election.

The Liberals ruled for three years during the ‘Fraser recession’, and the 1979-82 administration of David Tonkin, an optometrist, often gets short shift. Nonetheless, it had two very substantial achievements: the signing of the Roxby Downs agreement with BHP to mine copper and uranium in the state’s mid-north; and the conclusion of a landmark ‘treaty’ with Indigenous Australians effectively granting them control of the top end of the state, the ‘APY lands’

Labor only won the 1982 election after parliament granted approval of the Roxby Downs/Olympic Dam agreement. Despite Labor opposition, after one Labor member crossed the floor and was duly expelled. Labor later cobbled together the ‘three mine only’ policy to let the incoming Premier, John Bannon, 1982-92, off the hook and retain the uranium mine.

In the early 1970s the LCL split into urban liberals – the Liberal Movement – and country traditionalists – still the LCL. They argued about it, often bitterly, and then reformed as the SA branch of the Liberal Party. The Liberal Party has only very recently recovered from this dispute. The long weakness of its urban organisation stems partly from the fact that its electoral strength was in country SA.

SA had become the most urbanized of the states and its modern Labor political elite, was often drawn from a narrow metropolitan strata. The path for several generations was through a private college or half a dozen leafy suburb state schools, through the University of Adelaide, into law or trade union work, and so into Parliament. Premiers Dunstan, Bannon, Lyn Arnold, and Weatherill followed this path. As is the case elsewhere, this path has become dominated by ‘progressive’, left-liberal ideology and this has been reflected in the attitudes of the Labor Leadership.

The Bannon (then Arnold) administration of 1982-93, otherwise popular, bland, plebeian and fairly unadventurous, lost heart with the collapse of the State Bank and lost the 1993 election very badly. The government had tried to use the Bank as a source of local finance for businesses and so as an engine for more diversified growth in SA. The failure was as much in the execution of its investment strategy – very bad – as the design.

The Bank management borrowed heavily in the open market and invested more widely than in local business start-ups or expansions. With the collapse of the property bubble in 1990, it was left holding devalued assets worth much less than its borrowings. The three billion dollar loss thus incurred was disproportionately huge and was the first major turning point in recent SA economic fortunes. It represented a failure of Old Left, economic interventionist policies.

The Liberals rushed two of their stars back into parliament to defeat Bannon: John Olsen from the Senate and Dean Brown from private business. Brown then won the leadership vote. The subsequent Liberal administration, 1993-2002, under alternately the progressive faction, under Dean Brown, 1993-6, and then conservative faction, with John Olsen, 1996-2001, had in fact to spend much of its energy bailing out state finances, mostly by selling public assets.

These asset sales were resisted by Labor, which had created the need for them in the first place. Since Labor retained a veto capacity in the Legislative Council some rattings were required. Two duly eventuated.

However, the Liberal government appeared to spend the rest of its limited energy in intense faction fighting, which resulted in it almost, shockingly, losing the 1997 election and ten per cent two party preferred, down to 51.5 from 61, after Olsen replaced the, by then, unpopular Brown. Nonetheless, with the aid of the Labor defections it did manage to get the state’s finances into some semblance of order by 2000.

But it remained far from popular, and nor it did undertake the wider public sector shake out/restructuring which Kennett managed in Victoria. It was, simply, the only option to the discredited Labor party. In 2001 Olsen resigned as premier in a financial scandal and was replaced by last the Liberals’ chance, Rob Kerin, another country member.

By 2002 Labor had recovered somewhat from the total humiliation and disgrace of the State Bank loss. This was in some large measure due the obstinacy of its Leader, Mike Rann. Rann was an outsider, from London via New Zealand, appointed to run media for Don Dunstan. He got pre-selected for a safe seat and, with so few Labor MPs left standing in 1993, ten, he was a relatively clean skin Leader option. Rann was factionally unaligned and relatively unobligated.

Mike Rann clung in as Opposition Leader for seven years and got a nice swing in 1997. In 2001 Olsen got caught misleading parliament and resigned. After fighting a near draw in 2002 against the new Premier, amiable Rob Kerin, Rann got a dissident Liberal to support him as Speaker and thus cobbled together the numbers.

Labor was back from the dead and back in office.

Bob Catley, who was a professor and federal Labor MP, now sails quite a lot.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in