Robert Rauschenberg, like Autolycus in The Winter’s Tale, was a ‘snapper-up of unconsidered trifles’. Unlike Shakespeare’s character, however, he made them into art. Rauschenberg’s most celebrated piece, ‘Monogram’, on view in the grand retrospective of his work at Tate Modern, comprises, among other bits and pieces, a rubber shoe heel, a tennis ball, and a car tyre-plus-oil paint on stuffed angora goat. Next to it is another amalgam from the mid-Fifties, incorporating ‘paint, paper, fabric, printed paper reproductions, sock and army-issue flare parachute on canvas’. Modern-art sceptics — a dwindling group but not yet extinct — might conclude that this stuff deserves that time-honoured epithet ‘a load of old rubbish’.

It’s quite true in a way. But then, most art always has been created from low-value substances such as dried-up colours, coarse cloth and bits of rock. It’s what you do with it that counts. Walter Sickert put it well: ‘The artist is he who can take a piece of flint and wring out of it drops of attar of roses.’

Rauschenberg could do marvellous things with garbage. But only, it seems to me — and perhaps I reveal my own prejudices here — when he stayed close to the tradition of painting. This was, roughly, until the summer of 1964. That was when he won the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennale with his silk-screen paintings, a selection of which are beautifully displayed halfway through the Tate exhibition.

These consist of images from newspapers and magazines, reproduced on the canvas — just as they were in Andy Warhol’s exactly contemporary arrays of Marilyn Monroe and Campbell’s soup tins — by using the silk-screen technique. Unlike Warhol, however, Rauschenberg used this process to create a mosaic of imagery as diverse as the objects in his earlier work. Among these favourite photographic fragments, recurring in picture after picture, are a shot of John Kennedy from a presidential debate with Nixon, a nude Venus by Rubens, an eagle, and a Manhattan street sign. These were interspersed with bold stripes and splashes of paint.

Rauschenberg’s victory at Venice was a historic moment. It is regarded as the point at which everybody, even the French, noticed that New York had overtaken Paris as the international capital of art. His own reaction was to send a telegram to his studio assistants, telling them to destroy those silkscreens. He didn’t want to repeat himself. It was a bold gesture and a poignant one since, as the exhibition documents, he never had another idea nearly as good again. Consequently, the first half is essential viewing, the second much less so.

Rauschenberg (1925–2008) began as an anti-abstract expressionist (which make the fact that this retrospective coincides with the ab ex extravaganza at the Royal Academy a happy, though presumably random, coincidence). A generation younger than Pollock, De Kooning et al, he naturally rebelled against them. To Rauschenberg, their pictures were all about them, as the tag ‘expressionist’ implies: their feelings and their self-pity.

Rauschenberg particularly disdained the myth that artists have to suffer and hence feel sorry for themselves: ‘The worst state, the most anti-life, that you can put yourself into.’ Instead his works reflect the world around, sometimes quite literally. The glossy, monochrome panels of ‘White Painting’ (1951) form a sort of mirror. A friend and ally of Rauschenberg’s, the composer John Cage, called them ‘airports for the lights, shadows, and particles’.

But a whole career of producing shiny, monochrome paintings would have been distinctly sterile. His work became much more interesting when it got messier, which happened quite rapidly. Cage was instrumental in making another grittier early work: ‘Automobile Tire Print’ (1953).

To make this Rauschenberg glued 20 sheets of paper together and laid them out in the street, Cage then slowly and carefully drove his Model A Ford along it, with one inked wheel on the strip of paper. Thus an ordinary object made an image of itself.

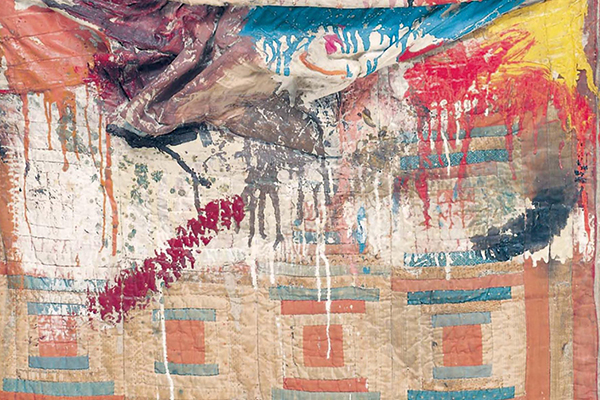

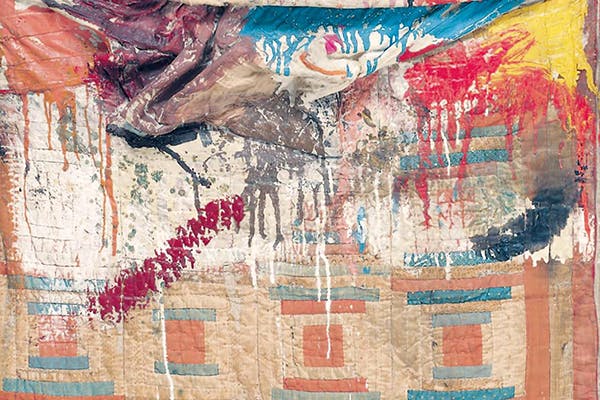

His Combines of 1954–64 consist of bits and pieces he found lying around and — as he put it — ‘dragged’ into his studio, all slathered with juicy, spattered paint. ‘Bed’ (1955), though hung on the wall, is quite like a real piece of furniture, with pillows, sheets and quilt. The artist worried art-lovers might want to crawl inside — although some might feel the spurts of pigment that cover it suggest the location of some terrible act of violence. (This piece, which includes 61-year-old toothpaste among its ingredients, must pose a particular challenge for conservators.)

At this stage it was as though Rauschenberg was grabbing hold of everything around him and amalgamating the resultant mixture of miscellaneous junk into a Jackson Pollock. But the paint was crucial. It glued the whole thing together — sometimes literally, but also metaphorically. The crazy energy of the brush strokes turns these jumbles of bric-à-brac into visual wholes.

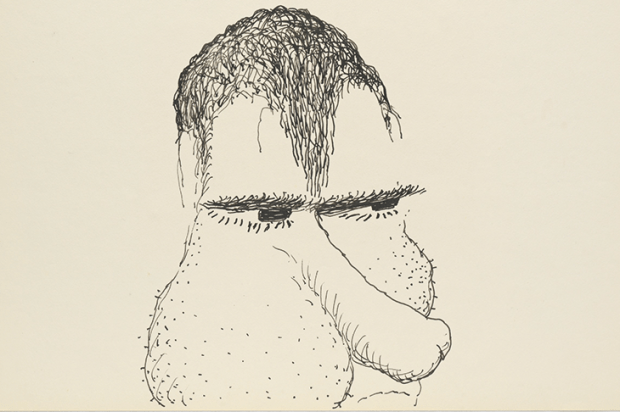

Next Rauschenberg found new ways of sticking images into his paintings. In the late Fifties, he discovered that he could create a ghostly replica of magazine illustrations and headlines by damping them with lighter fluid and rubbing from behind. He added touches of watercolour to create works on paper in which stray faces and bodies loom out as if through a soft, grey mist.

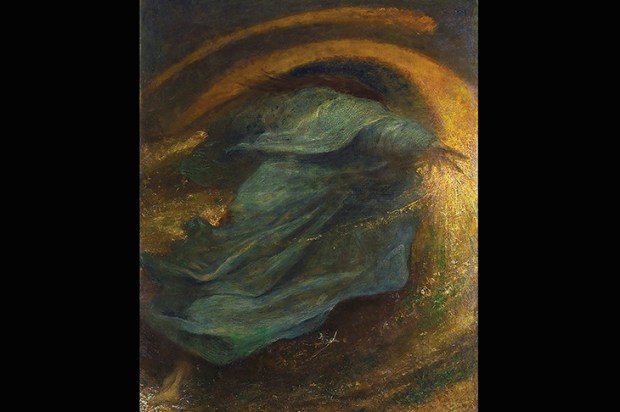

Using this medium, he made a delicately translucent cycle on the theme of Dante’s ‘Inferno’. These little pictures conjure up a mid-20th-century Hades, in which, for example, the giants the poet sees in the pit of Malebolge are represented by three Olympic weight-lifters from Sports Illustrated. Those who would like to investigate this aspect of Rauschenberg’s work further are recommended an excellent exhibition containing many more transfer drawings from the Fifties and Sixties at the Offer Waterman gallery, 17 St George St, W1 (until 13 January).

When I visited Rauschenberg, he left the television on all the time while we were talking. The volume was right down, but in the background there was a constant flickering accompaniment of random images. ‘I am always surprised’, he remarked, ‘that in this day and age you don’t have to keep up with everything: you don’t have to look for information, we’re swimming in it.’ This was his true subject. It makes his work of more than half a century ago seem oddly up-to-date now that we have entered the fresh inferno of the internet age.

The post Trivial pursuits appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in