After we were married, my husband and I went on honeymoon to Mexico. We drove across country east to west, then north to Mexico City, to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe where I prayed for a baby. My husband, the least judgmental of atheists, sat happy in the babble of ladies all talking loudly, conversationally, to God. In April this year, with a vomity newborn on my shoulder, I made a nightlight out of a picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe and some fairy lights. Now, eight months later, as we begin each evening’s slow, hopeful descent towards bed, I take the stout and opinionated baby to say goodnight to her. Goodnight Virgin Mary I whisper, and he leans forward, rips the battery pack out of the fairy lights and lets it fall, clattering on its wires. Routine is vital, I’m told.

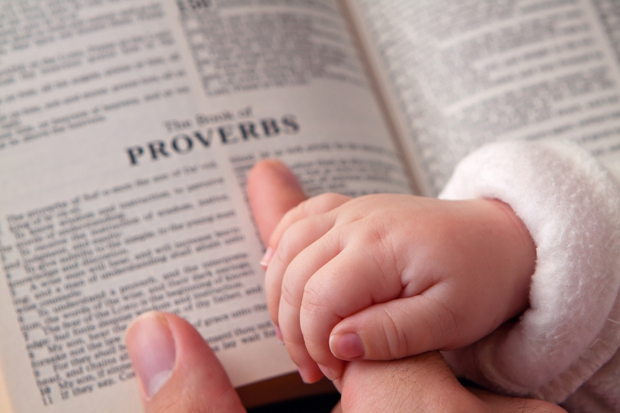

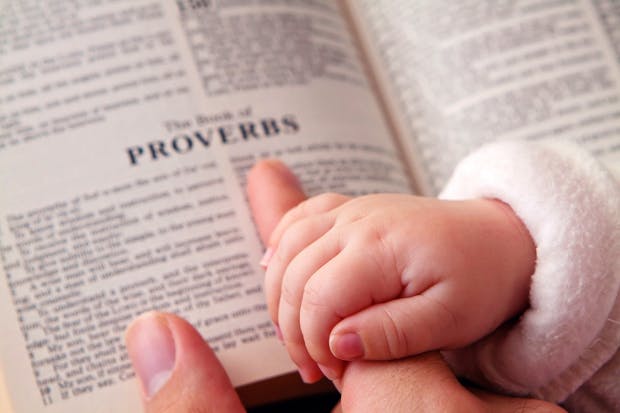

He’s starting to recognise words now, ordering his world into dog, duck, car, and I’ve recently found myself hesitating for a half-second in front of the nightlight. It’s one thing to choose a faith for yourself, to muddle, as I did, from uncertain Anglicanism, through atheism into crazy-seeming Catholicism and find yourself inexplicably at home. It’s quite another to introduce a pantheon of invisible beings to a new human. Dog, duck, car, angel, saint.

Richard Dawkins, whom I admire in many ways, says that to bring up your children Christian is to abuse them. When the kid realises that the ‘sky fairy’ doesn’t exist, he’ll be hurt and angry, says Dawkins. I have faith in the sky fairy but perhaps the baby, when adult, won’t. Will the midget look back and feel betrayed? Will I be able to look him in the eye and say: son, this is really what I believe?

This Advent, as I’ve worried away, forgotten strands of my own childhood have floated back. When I was very young, three or four say, I chatted away to God in the manner of a Mexican lady. My family weren’t religious but it seemed natural to me, as I remember it. I suspect that children are natural deists. We’ve been religious in one way or another for at least tens of thousands of years. It’s in our bones.

Nor do I think it’s damaging to believe in the sky fairy, or any fairy for that matter. When I was six or seven, on my birthday, I received a letter from the fairies. It was written in ink on a long scroll of bark from the Tibetan cherry in the garden. The letter directed me to a flowerbed where a gold locket lay hidden — a gift from fairy-kind to me. I don’t believe in fairies (I’m not that Catholic) but I can still recall the magic of that day. My world, whose previous high points were pudding and the possibility of a puppy, stretched suddenly wide open.

Dawkins would call that letter a pointless lie, but it provoked in me, for the first time, a feeling of wonder; a sense that the world is not to be underestimated. I feel this seeing pictures of space nebulas and the weirdly evolved creatures of the submarine deep. I feel it when I realise how profoundly the roots of all our ethics are wrapped up in Christianity and how unnervingly wise the tales and parables of both New and Old Testaments can be.

I grew up, as did most of my generation, on a drip-feed of Bible stories, learnt mostly half-heartedly, at school. Noah, Jonah, the paralysed man lowered from the roof, the amazing, multiplying fishes. The stories lay dormant in my head. If I thought about them at all between the ages of ten and 25 it was with an indifference. Then, quite suddenly, in my thirties, they began to speak to me.

But the Bible’s full of vengeful nonsense, an irritable atheist might say. Look at the story of Adam and Eve, of the Fall and the doctrine of original sin. As a teenager I would have agreed these were terrible teachings. As an adult, I find the thought of original sin a great relief. If we’re all flawed, it means we’re all in it together, easily tempted, imperfect. This rings true. ‘There is a crack in everything; that’s how the light gets in,’ sang the late Leonard Cohen. Original sin makes for mercy.

My teen self liked to ridicule the verse about the rich man, the camel and the eye of the needle. ‘Camel is a mistranslation of the Arabic for rope!’ I used to say. ‘Daft old Christians! And what’s wrong with being rich?’ Well, nothing, except that as it turns out, according to behavioural psychologists, that the verse is bang on. It just is exceedingly hard to be rich and generous. The banker philanthropist Jonathan Ruffer has written about it in this magazine. Cash sticks to cash. You’d like to give more to charity, but there’s the school fees… pool maintenance. The poor give a far higher proportion of their income away.

Paul Piff, a psychologist at the University of California, has found that those who’ve lucked out in life almost invariably think of themselves as superior to others. They, we, are more likely to run red lights and dodge tax. The kingdom of heaven recedes. I want my boy to be rich, but I also want him to understand the dangers. I want the parables to be logged in his mind, waiting submerged.

As I write this, the fat little midget has a fever, though not a serious one. I’ve been standing in the dark by his cot and counting his hot breaths with my iPhone stopwatch, wishing there was something I could do. I looked to the nightlight, said a prayer, then worried about how on earth to explain to him why a good God allows such suffering in the world, so many unanswered prayers. That old chestnut. Well exactly, you might say: better bin God. But the questions don’t disappear if God does; they only get worse. Why be good in a godless world? What’s the point? Why treat others as you’d wish to be treated if you’ll never see them again?

In my late twenties I tried to make sense of it all. I paced about London, often longing for somewhere quiet to sit and think, and found to my surprise that there were places all over town that seemed designed for the purpose. The doors of Catholic churches were always open. They were warm inside, with an oddly comforting little nightlight flickering red over the altar. I’d sit with the smell of candles and my mind would calm. Whatever he believes, in the end, I want the church to be a refuge for my son.

The post Why I’m telling my son about the sky fairy appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in