Back in 1978, a young and already successful Steven Spielberg told a bunch of would-be moviemakers at the American Film Institute not to ‘worry if critics like… Molly Haskell don’t like your movies’. Four decades on, and just in time to mark his 70th birthday, Haskell has written a biography of Spielberg for Yale’s series of Jewish Lives. Since the series is essentially celebratory, and since Haskell is one of the hanging judges of feminist film criticism, this is an interesting commission.

But is it a wise one? Whatever you think of Spielberg’s work, its emphasis on motherhood and apple pie hardly makes it feminist fodder. Little wonder Haskell hesitated before agreeing to the project. ‘I had never been an ardent fan [of Spielberg],’ says this lover of European arthouse cinema. In fact, she and Spielberg have nothing in common. Where she goes for ‘irony’ he goes for the ‘inspirational’. Where she adores ‘brooding ambiguity’, he loves ‘moral clarity’. And while they ‘both had blind spots’, there was no getting away from the fact that his ‘blind spots were my SEE spots, and vice versa’. As Fred said to Ginger, ‘Let’s call the whole thing off.’

Yet Steven Spielberg: A Life In Films turns out not to be a hatchet job. Haskell has barely a bad word to say about the man and his movies. Even when she has Spielberg on the ropes, she invariably pulls her punches. Take her comments on his love story Always. She isn’t wrong when she says the movie fails to ‘imagine the full spectrum of adult heterosexual emotions — attraction, flirtation, desire’. But she doesn’t add that since that criticism can be made of all Spielberg’s work — indeed, that he isn’t really interested in the relations between men and women, period — he is therefore crippled as an artist, and his movies only ever likely to be of sociological interest.

The wider case against Spielberg is easily made. He is the man who killed the idea of cinema as a serious art form. For their first half-century or so, the movies were just that — the movies: popular entertainments with one eye on the bottom line and the other on the lowest common denominator. But during the Fifties and Sixties things began to change. Following the breakup of the studio system, young moviemakers were freer than their forebears not just to tell different kinds of story but to tell them in different ways. In place of classical Hollywood’s seamless literalism — unobtrusive camerawork, invisible editing, explicatory dialogue, good goodies and bad baddies — came cinema full of formal experiment and moral doubt.

Spielberg wasn’t interested. As Haskell points out, he spent the high days of the Sixties apprenticed to the TV department at Universal. While his contemporaries — Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian De Palma — were graduating from university film departments and nurturing ‘grand plans for remaking the [Hollywood] system’, Spielberg (who hadn’t the grades to study beyond school) was learning his craft on the job, directing episodes of story-dominated series like Marcus Welby, M.D. and Columbo.

Before long he was transplanting their old-fashioned virtues back into the movies. Despite its half-cocked, sub-Ibsen sub-plot, Spielberg’s breakthrough picture, Jaws, was little more than a pumped-up Saturday morning serial. But it took $260 million (on costs of $8 million) and changed the terms of the debate. All of a sudden, Haskell’s cineaste comrades, who’d spent the past few years talking about Fellini and Godard, were obsessed with publicity and profits: ‘saturation marketing, must-see summer films, the advent of the blockbuster, and then the high drama of the weekend opening and the box-office intake.’

Now I’m no Spielberg fan, but this isn’t on. The fact is that Haskell and her aesthete pals had been kidding themselves about the movies, which had always been machines for making money. What Spielberg can be blamed for, and what the Freud-fuelled Haskell inexplicably skates around, is having infantilised movies and their audiences. If you ever glance at the cinema listings and wonder why there’s nothing the even vaguely mature might want to see, blame Spielberg. Terror of adulthood is his primal theme. Indeed, Spielberg, whose relationship with his father was troubled, so identifies with Peter Pan he actually made a movie — Hook — in which Peter has become a (troubled) man.

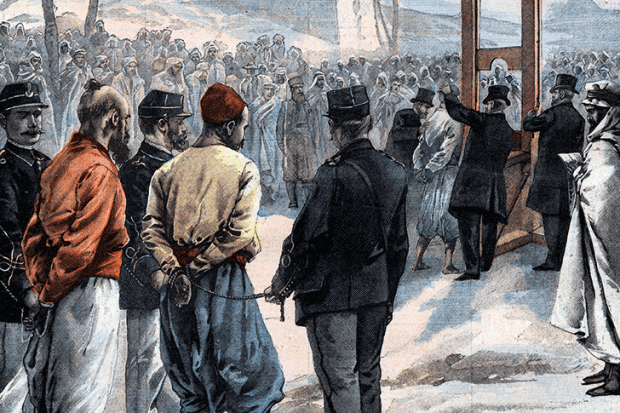

Not that Spielberg hasn’t strained after seriousness. There was his movie of Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Colour Purple, which Haskell rather too defensively argues was ‘more than a bid for the Oscar’.There was his biopic of Lincoln (scripted by the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Tony Kushner), a dialogue-drenched movie of draining dullness that Haskell calls ‘the very essence of gravitas’. And there was his picture of Thomas Kenneally’s Booker Prize-winning Schindler’s List, with which, Haskell claims, Spielberg finally ‘confronted his own Jewishness’. Hmm. There’s no denying the beauty of the film, with its sombre monochrome imagery punctuated by what Haskell calls the ‘red smear’ of a hand-tinted coat worn by a young Jewish girl. But what was it Adorno said about ‘no poetry after Auschwitz’?

Haskell argues that the red coat ‘individualises’ one of Hitler’s otherwise numberless victims, and I suppose it does — but since it also makes the picture look like a pop video, at what cost to Spielberg’s indubitably solemn intentions? As for her suggestion that ‘Historians, pledged to the truth and nothing but the truth, will always disagree with critics, whose allegiance is to art,’ it is romantic hot air. Art worthy of the name is no less pledged to the truth, and while no critic is obliged to accept Lukacs’s dictum about fiction’s need to dramatise the ‘social totality’, it would be well for any critic talking about Schindler’s List to at least acknowledge the argument.

But like Spielberg himself, Haskell seems to know little about anything outside the movies — and she isn’t even sure about them. She tells us that Saving Private Ryan won the Oscar for Best Picture. It didn’t. She tells us that Chiwetel Ejiofor took the Best Actor Oscar for 12 Years a Slave. He didn’t. And she tells us that the divine Karen Allen was ‘deglamorised’ for Raiders of the Lost Ark. Trust me, love, she so wasn’t.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in