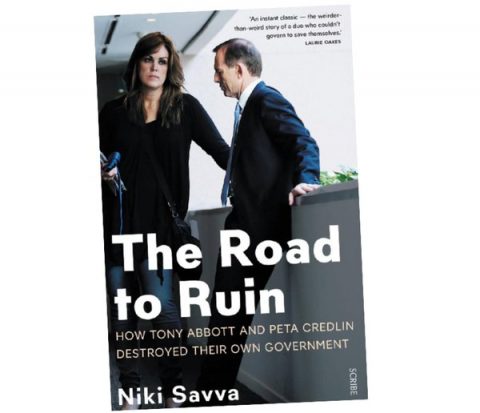

At the beginning of last month, until I was rudely interrupted by a Jordanian hacker, I started writing thoughts on Niki Savva’s notorious “Downfall”-style chronicle of recent Australian politics, “The Road to Ruin: How Tony Abbott and Peta Credlin Destroyed Their Own Government”.

At the beginning of last month, until I was rudely interrupted by a Jordanian hacker, I started writing thoughts on Niki Savva’s notorious “Downfall”-style chronicle of recent Australian politics, “The Road to Ruin: How Tony Abbott and Peta Credlin Destroyed Their Own Government”.

As my friends know, I never read books when they come out, instead leaving it to chance whenever a second-hand copy eventually falls into my hands. With “The Road to Ruin”, that chance finally came in November, months after all the initial post-release excitement and scandal has dissipated.

Since Savva’s book first came out, people have been approaching me on the street, asking “Arthur, you were there; was it really that bad?” Actually, no one has been approaching me on the street to ask that, but on the occasions when the topic would come up in conversations with friends I always volunteered my opinion that from what I have heard of the book, yes, it was that bad.

Now that I have finally had the chance to read it – and blog about it post-hack – I can honestly repeat: yes, it was that bad. I won’t venture any new theories about the exact nature of the relationship between the prime minister and his chief of staff, except to say that it was strange, unprofessional, dysfunctional, distracting, destructive and it ultimately cost him his position (and her hers); the fact he still fails to acknowledge to this day, which tells me he has learned nothing from his first stint as the prime minister and no matter how bad Malcolm Turnbull is performing in the top job, Abbott 2.0 is simply not a viable alternative.

Credlin and her unorthodox (mis)management style drove the Coalition government to distraction all through the first half of its first term upon returning to office. This is not to say that Credlin is exclusively to blame for the government’s uninspiring performance – far from it; there is certainly enough blame to go around – but she was perhaps the greatest internal distraction and obstruction to a proper functioning of the executive.

I first had the exposure to the new way things were to be done when I put my hand up to fill an adviser position. As per the normal practice, all ministerial staff appointments have to be vetted by the “star chamber”, which consists of the PM’s chief of staff and several other senior people.

After having spent 14 years working for the Liberal Party in various capacities I didn’t really expect any problems until I became aware of a new directive that all ministerial advisers were to be from now on Canberra based.

To cut a long story short, I was lucky enough to get a rare exemption and thus able to stay in Brisbane while travelling to Canberra for the parliamentary sittings and as otherwise required. But it was an absurd idea to start with, which denied the government the talents of many experienced operators who were unwilling or unable to uproot their whole lives and relocate to the capital.

Its main purpose was not to enhance in any way the operations of the ministerial offices but for Credlin to be able to maintain a better watch and control over the hundreds of most senior government staffers. That this brilliant new practice would have enclosed the people on whom the ministers rely on the best political and policy advice in a Canberra bubble, where they would have limited opportunity to keep the pulse of what the rest of Australia is thinking, doesn’t seem to have crossed the PMO’s mind.

But that was just the beginning. Writes Savva on page 56: “[The Department of] Finance had also been instructed by Credlin not to release funds by travel by ministers unless there was a written letter of authority from her. This made it especially difficult for the foreign minister given the amount of travel she undertook. Bookings would be made, then the office would have to wait for approval. There were times when approval came only within twenty-four hours before take-off.”

But it was far worse than that – and now I can add two cents of my own, which you won’t find in Savva’s book – the three in the foreign affairs and trade portfolio (Julie Bishop, Andrew Robb, and my former boss Brett Mason as the parliamentary secretary) had to submit to the PMO for approval our proposed forward travel plans for the next six months, including the destinations, the reason for going, and justifying the necessity of the trip.

To compile our document we would consult with Julie to find out where she wanted us to go that she couldn’t, including representing the Australian government at multilateral meetings that she wasn’t able to attend. We would also consult the Department for their input as to which of Australia’s overseas relationship would need some more face-to-face love in the short term.

Lastly, we would do our own thinking on how to best advance Australia’s national interest bilaterally and multilaterally in the areas where we were specifically assisting Julie – foreign aid, the Pacific region, and the New Colombo student scholarships. We would then get our six-month plan okayed by Julie and then submit it to the PM’s Office.

Sometime later, our plan would come back to us with about one-third of our 10-15 proposed trips crossed out; rejected, mostly without any reasons given. You see, Credlin, in her infinite wisdom, was deciding which of Australia’s international relationships were important and which ones weren’t, and what was and what wasn’t in Australia’s national interest.

If it was frustrating for us in our lowly parl sec office, imagine how infuriating it was for the two senior cabinet ministers in charge of Australia’s foreign and trade relations to be double-guessed and vetoed by the prime minister’s chief of staff, with her zero interest in and knowledge of international affairs.

Credlin’s decisions were sometimes portrayed to us as an exercise in cost saving. This would have been easier to swallow were we able to see the evidence that the Abbott government was actually serious about cost cutting or economic management in general.

Sure, overseas trips cost money, but they pale into insignificance next to the National Broadband Network, the National Disability Insurance Scheme or the Paid Parental Leave initiative. You can’t run middle-power foreign relations on a smell of an oily rag; diplomacy depends on interpersonal relations and these can only be built through face-to-face interactions.

Yes, the overseas travel was very exciting but it wasn’t a junket for anyone concerned. Credlin’s interference wasn’t really about money but about asserting control; another example of obsessive micromanagement of ministers and their staff by the PMO.

The Abbott-Credlin duumvirate, their joint prime ministership, will forever remain one of the most bizarre chapters in the Australian political history.

Its internal political consequences and outcomes did much to sour my long-standing enthusiasm for political work and eventually led directly to my exit after almost 16 years as a federal Liberal staffer – but that’s a story perhaps for another time and occasion.

You can criticise Savva as many have done for her unjournalistic practices, her clear bias and alleged conflicts of interest, but none of it changes the essential facts as amassed and presented by her. Kill the messenger, but the message remains.

Most of us on the inside throughout those days knew it would all end in tears. Now you know why.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in