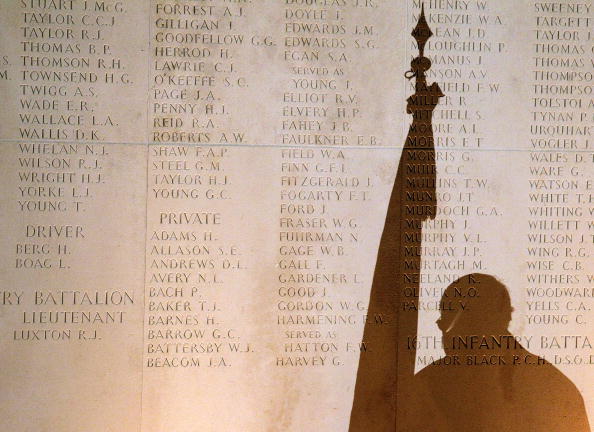

Once Australia’s premier veterans’ advocacy organisation, the Returned and Services League is in rapid if not terminal decline.

Once Australia’s premier veterans’ advocacy organisation, the Returned and Services League is in rapid if not terminal decline.

Its leadership is failing the broad membership, which continues to provide support at local sub-branch level.

The RSL national leadership has failed the challenge of the 21st century as sub-branches close, local leadership ages and resists change.

Young veterans shun the organisation.

Charlie Lynn’s Flat White article Leadership crisis dogs RSL is accurate, timely and significant.

However, Lynn does not address the broader issue of why the RSL has “not adapted to change and has vacated the field of public debate”.

The RSL’s problems are broader than NSW where the erstwhile National President Rod White and his former state board colleagues face serious misconduct allegations.

The malaise in the RSL is national.

In 1916 the RSL was established as an organisation for ‘returned men’ only.

This term referred to those who volunteered to join the 1st AIF, had served overseas, and ‘returned’.

The RSL is not a national organisation but rather a federation of state organisations established under separate state legislation.

These two terms, ‘AIF’ and ‘returned men’ (now veteran) resonated across the RSL until the 1980s as they meant that membership was restricted to those who met these criteria.

Those who enlisted but did not go overseas during the world wars (500,000 men and women) were denied membership of what became the core grouping in local communities across the country – the RSL sub-branch.

That included those who defended Darwin against the Japanese because they were not “returned”.

It is a hurt that resonates even today among their children and grandchildren.

Members of militia battalions who fought on the Kokoda Trail and at Milne Bay in the early days of the Japanese War were also excluded – because they were conscripts, not AIF.

Even though militia members were accepted in 1944 the damage was done creating a permanent rift among many who vowed never to join.

A more recent example is that of a father who served four years during WW2 in Australia whose only son, a conscript, was killed in Vietnam and commemorated by his local RSL.

An RSL the father could not join.

Even with the belated acceptance for reasons of organisational survival of those who served in the regular and reserve forces post-World War II, old prejudices remain.

The RSL structure, the financial dominance of some state branches, the penury of others and its blinkered attitude toward organisational change has enabled and encouraged the rise of more dynamic ex-service organisations outside the RSL.

The RSL has demonstrated the singular power of turning potential organisational highlights and opportunities into negatives.

This is emphasised by the organisation’s inability to embrace more recent veterans; its failure to plan strategically to meet the demand of the 21st century and its failure to advocate strongly for the issues so clearly enunciated in its constitution.

There is no enthusiasm to investigate governance models better suited to the present combative environment where professional lobbyists vie for the ear of the federal government on a daily basis.

The days of any government deferring to the wishes of its warriors who have defended the nation is no longer a given.

As its World War I founders and leaders faded away by the 1980s the RSL gradually became a Canberra-centric organisation.

With little background in the organisation until their appointment they have generally – no pun intended – proved unsuitable to the role.

They have proven unable or unwilling to enter the public debate on those core issues that are fundamental to the members of the RSL.

A caveat here, however, is necessary.

The national RSL president and by implication the national headquarters is starved of funds. It still relies on the annual subscriptions from a diminishing membership for the bulk of its funding.

Some state branches have accumulated great wealth through their historical business acumen, as for example Queensland with its art union prize homes and NSW through its clubs and poker machines.

There is certainly no broad enthusiasm to fund national HQ’s advocacy role for the broader membership.

The onus clearly rests with the national executive to resolve the decline in respect for the organisation among its existing and potential membership and the broader Australian defence community.

This same national leadership must steel itself for some difficult decisions to abandon the past and embrace the future.

They must also overcome the mistrust at sub-branch, state and federal levels to convince the membership they have not only a vision for the future but the will to introduce it.

They must certainly convey that view to those eligible ADF members who shun the organisation in droves.

Change for the RSL as a national organisation can either be embraced or denied.

The latter is not an option.

Kel Ryan is a Life Member of the RSL in Queensland. He has also held elective office in a number of other ex-service organisations. He is currently completing a PhD on Pathways for the advocacy of the issues of the Australian Defence Community in the 21st century.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in