Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Snow Maiden has not received a professional staging in the UK for 60 years. Think about that for a moment, and what it says about British operatic priorities. Sixty years of Massenet and early Verdi, of Manon Lescaut and Donizetti ‘rediscoveries’. Not that those aren’t worth having, as part of a healthy and balanced operatic diet. But the fact that during those six decades no major company showed any curiosity about an acknowledged masterpiece by one of the 19th century’s most prolific and original musical dramatists is perverse, to say the least. The musicologist Richard Taruskin, who’s nobody’s idea of a soft touch, points out that in addition to his own 16 operas Rimsky-Korsakov was also largely responsible for establishing operas by Glinka, Borodin and Mussorgsky in the repertoire. Rimsky, he concludes, is ‘perhaps the most underrated composer of all time’. I’ll buy that.

Well, The Snow Maiden is back now, in all its fairy-tale wonder. Is that part of the problem? The term ‘fairy tale’ — especially when coupled to another two words too often and too glibly attached to this composer, ‘folk opera’ — doesn’t remotely cover the richness of what Rimsky-Korsakov achieves here. Snegurochka the Snow Maiden, illegitimate daughter of winter and spring, yearns for love and a warmth that can only ever mean her doom. Rimsky, a nature-worshipper with a powerful instinct for myth, manages to balance the story’s symbolism of seasonal renewal with an intensely human mixture of pathos and joy, sometimes in the same musical instant. It’s never heavy-handed. The clarity and colour of Rimsky’s storytelling draw you in even as a sense of something eternal and implacable pushes through from beneath, occasionally breaking the surface, like a mammoth erupting from some Siberian glacier, in massive hymn-like choruses.

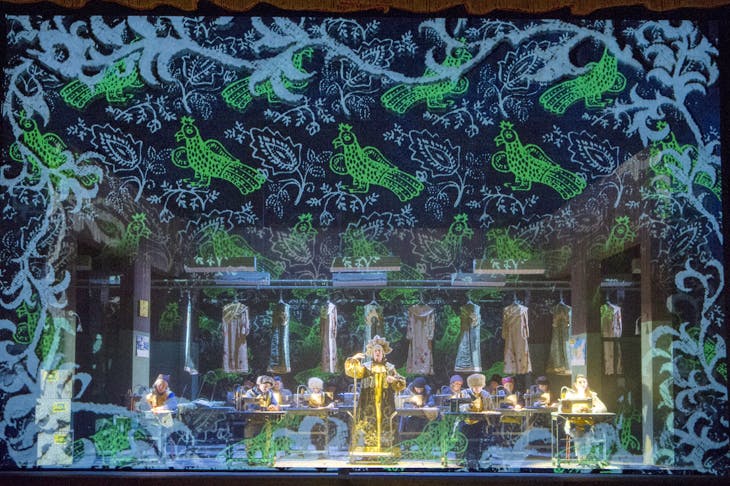

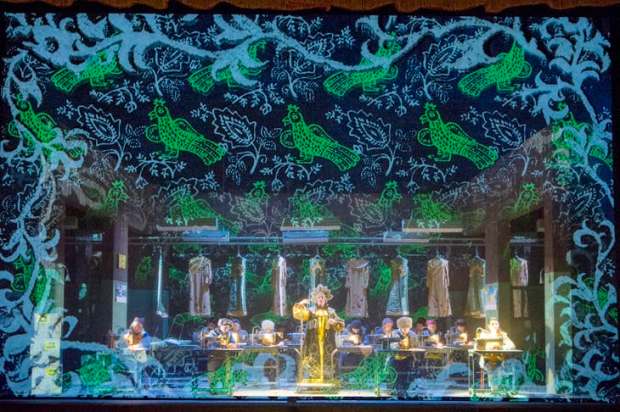

Give or take a few cuts, John Fulljames’s new production for Opera North takes the piece seriously — and that includes the supernatural element, which can surely never in this opera’s 135-year history have looked so fantastic. In Will Duke’s animated video projections frost curls its tendrils around the stage, embroidered flowers blossom and twine, and Aoife Miskelly’s Snow Maiden trails flurries of snow. The designs swerve all over Russian history, from the Ballets Russes to the Eastern Bloc bleak-chic of everyone’s favourite totalitarian dictatorship, the USSR (fluorescent strip lights having replaced trenchcoats as the great operatic design cliché of the moment). And in its own playful way, it works, though the ugliness of the modern scenes (the village girls work in a clothing factory) jars a bit. Fulljames and his team create a different visual identity for each of the story’s various layers, and the business of decoding the costume changes can be something of a distraction.

Fulljames’s heart is definitely in the right place, though, and there’s enough visual enchantment elsewhere in the show to carry it through — quite apart from the performances, which are almost all captivating. Miskelly was a touchingly lovelorn heroine, with a voice that’s capable of crystalline purity and tremulous ardour. Her otherness was striking, even when she wore jeans and a factory apron prior to her final glittering transformation, and Elin Pritchard was cleverly cast as her vodka-swilling, very much flesh-and-blood love rival Kupava — just as Heather Lowe nicely caught the sunny bravado of the peasant lad Lel. Phillip Rhodes as Mizgir came across too aggressively to make a wholly likeable love-object for the Snow Maiden, but as the magus-like Tsar Berendey, Bonaventura Bottone’s Gilbert and Sullivan-ish tenor trod Rimsky’s line between humour and gravity very effectively. Yvonne Howard’s compassionate, velvet-voiced spring goddess ennobled every scene in which she appeared.

None of these voices was especially weighty, but that didn’t matter, given the luminous sounds rising from the pit, and the all-pervading glow of tenderness and warmth that Leo McFall drew from the Opera North orchestra. If I’ve a reservation, it’s that McFall may have been slightly too gentle: the chorus of Welsh National Opera would have made the walls shake. But boy, that score! It’s customary to drool over Debussy’s and Strauss’s orchestration, but Rimsky is their equal — magically fresh, ravishingly atmospheric, his endlessly generous flow of melody lit from within by the horns, and glistening with harp and bells. If McFall sounded like he didn’t want it to end, who could blame him? Hopefully the next UK production won’t take 60 years to arrive. And maybe that one can be performed without cuts.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in