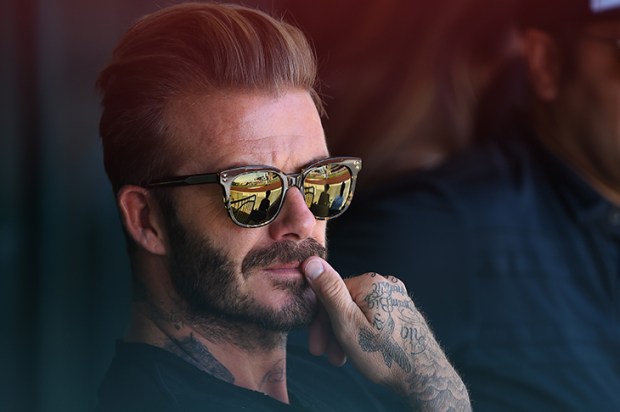

Whatever calamitous infelicities David Beckham did or did not email to his publicist, few will doubt that he has lived to rue the day. Nevertheless, I’ll bet teeth that he is pointing his ruing in the wrong direction: that he is tormented by the moment he pressed ‘send’ — but not similarly kicking himself for hiring a publicist in the first place. It will be left to thee and me to wonder what was the point. When you are already richer than God, you are one of the sporting legends of your generation and your face would be recognised by a yeti in the wastes of Siberia — why might you ever want to fork out gazillions to a man who describes himself as ‘managing David Beckham’s global communications strategy’, which translates as ‘making him even more famous’?

The stricken footballer is not alone. Practitioners of these dark arts are now a sine qua non for everyone from the wannabe to the more established twinkles in the galaxy. One editor of a magazine that specialises in entertainment and celebrities estimates that 85 per cent of those who grace his pages dance to the tune of their personal publicist. He is incredulous when I promise him that it was not always so; that it is, in fact, a very recent phenomenon.

Twenty years ago, at the behest of the Sunday Times, I went to interview Carrie Fisher, armed only with her home address and telephone number, in case I got lost. I found her in her garden, pushing her daughter Billie on a swing. I then joined them for Billie’s bedtime songs before Fisher and I sat on the floor by a big log fire, drank far too much wine and talked until midnight. Just before I toppled into a taxi, we agreed which bits I would not print. The next day I wrote a warm piece about a remarkable woman, without mentioning the… well, never you mind… and it was job done, exactly as it was after several days spent with Arianna Stassinopoulos and Sonny Bono.

Only two decades on, could it happen now? ‘Inconceivable,’ says my younger editor friend. Today, the personal publicist will allow a maximum of 45 minutes and choose the anonymous venue — probably a hotel room. He or she might stipulate limits on the questions, demand to approve the finished piece and will probably sit in on the interview to ward off conversational intimacy. Should it be a TV talk show, the grip will be even tighter.

Make no mistake: the personal publicist has nothing in common with the traditional PR machine that has always played midwife to the launch of a book, play, film or sporting event. The machine concentrates on the project before the person; an interview with, say, the leading actor is only part and parcel of the wider aim to nudge interest and consequently ticket sales. Few, indeed, hold the personal publicist in greater contempt than the more experienced public relations expert. ‘We don’t share the same DNA,’ sniffs one such. The personal publicist gives small damn for the bigger picture. Unlike an agent or manager, who works for a percentage of earnings and thus is invested in the long-term success of the collective project, the personal publicist is paid a fee to concentrate on the individual, even at a cost to the rest.

The first personal publicist in Britain was probably the now-disgraced Max Clifford, whose discovery and exploitation of the niche was perniciously brilliant. Whether it was with Bienvenida Buck, a courtesan who ached for what she always called ‘respect’, Antonia de Sancha, a spurned mistress who ached for revenge, or little Jade Goody, who ached for some abstract notion of Fame, his method was the same: he would arrange for them to be seen, constantly, on his avuncular arm. He escorted each of them with the same self-righteous look of protective outrage that anybody might start nosing around his client — and in the process ensured that they would.

What was even cleverer, and has been emulated with varying degrees of success since, is that Max realised the importance of having the client develop an emotional dependence on him. (Would you wish to have Max Clifford announce your death to the world? Such was her dependence that Jade Goody, poor child, apparently did.) His timing was perfect: just as the previous must-have accessory — the psychotherapist — fell from vogue, along came the personal publicist, who used the exact opposite technique to reach the same goal of continuing reliance.

The therapist’s trick was to assure the ‘talent’ that they were truly messed up — but don’t worry: stick with me and I’ll fix it. The personal publicist assures that same, self-centred, insecure talent that they are brilliant. The best in the team. The star in the cast. The immortality for which you yearn is just out of reach — but don’t worry; stick with me and I’ll fix it. You deserve top billing. You deserve recognition. You deserve a knighthood. Because you’re worth it.

Of course, others are alienated along the way: the rest of the team, fellow cast members, the constrained journalist. But that only draws the talent closer to the person who promises to protect them from hostility. Now, as is the way of celebrity, bauble envy has set in — ‘He’s got one so I want one’ — and thus the personal publicist becomes the accoutrement de nos jours.

Although older, wiser heads eschew him (Dames Maggie Smith and Judi Dench and Sir Anthony Hopkins do not boast a publicist among their professional entourages; did you think they would?), the younger and more gullible fall like ninepins to pay the most to people they need the least. Given that Andy Murray is the world’s No. 1 tennis player and current Olympic champion — not to mention so free of scandal that there is not even a need for ‘crisis management’ — one might imagine that sponsorship from makers of plimsolls would follow without any assistance beyond that of a competent agent. Yet Murray has a personal publicist; heavens, Mum should know better.

In the scheme of things, it probably doesn’t much matter. Certainly the public is lied to a bit more often as a result of the stunts — but we are used to that, and the lies pertain largely to those of little consequence. All the same, I do feel rather sorry for the none-too-bright fame junkies who, like as not, end badly from the deal.

After all, where is Bienvenida now? Or Antonia? And David Beckham might yet reflect that had he not hired someone with whom he believed he could so enthusiastically conspire to get a gong, he might actually have got one.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in