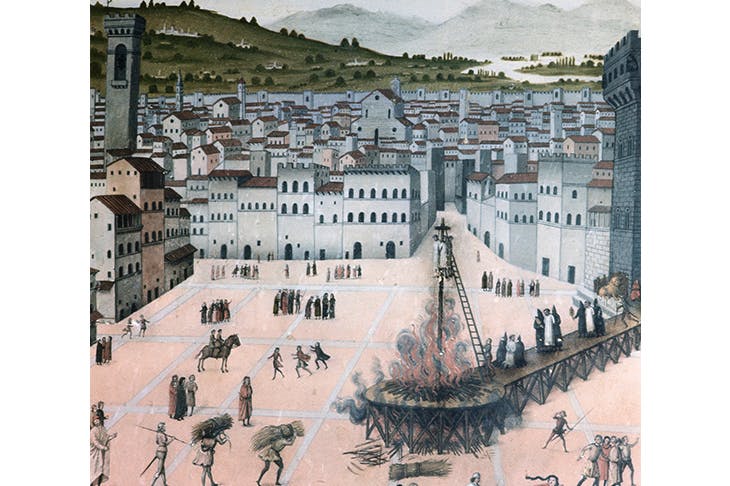

The business of banking (from the Italian word banco, meaning ‘counter’) was essentially Italian in origin. The Medici bank, founded in Florence in 1397, operated like a prototype mafia consortium: it rubbed out rivals and spread tentacles into what Niccolò Machiavelli called the alti luoghi (‘high places’) of local power interests. Undoubtedly, Medici money was at its most arrogant under the dictatorship of the merchant-poet Lorenzo de’ Medici, whose supremacy was dramatically challenged in the Pazzi conspiracy of 1478. Amid a fury of dagger blows in Florence’s cathedral (of all places) Lorenzo narrowly escaped assassination by bravos in the pay of the rival Pazzi family. In retribution, 70 presumed conspirators were publicly torn alive from groin to neck. In mobster parlance, this was a ‘balancing of accounts’.

Machiavelli, born in Medicean Florence in 1469, was perhaps not quite the devious schemer of popular imagination. As a man of some political scruple he was appalled by the irreverence shown by the Pazzi plotters. The signal for the attack came just as the priest had raised the host at High Mass; Lorenzo managed to barricade himself behind the bronze sacristy doors, but his younger brother Giuliano died under knife thrusts. The murder in the cathedral served only to consolidate Lorenzo’s popularity as a Florentine strongman. Under torture, the ringleaders confessed allegiance to the slyly watchful Pope Sixtus IV, who favoured the Pazzi over the Medici as bankers to the Holy See.

In her new biography of Machiavelli, Erica Benner asks how the city that gave us Botticelli and Cellini could have been so appallingly violent. Certainly the Victorians who toured the Uffizi with copies of Walter Pater did not concern themselves much with the city’s blood-soaked past (preferring to bask in the romantic aura of Mr and Mrs Robert Browning). Yet, as Machiavelli knew too well, the intellectual energy of Renaissance Florence was not confined to painting and literature; quite as much money and thought went into the art of political ‘double-speak’ and ‘currying favour’ (Benner has a weakness for cliché) with bankers, popes and princeling-diplomats.

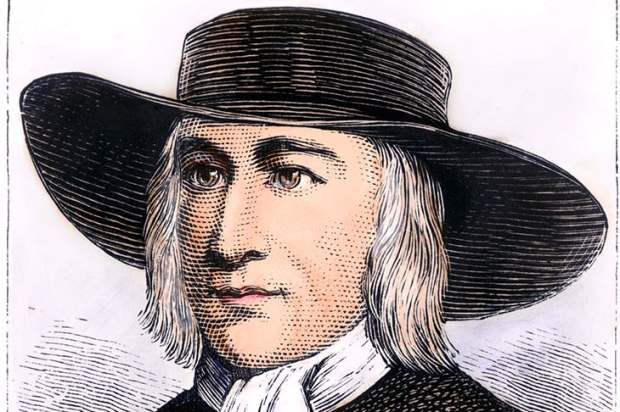

Written in the historic present (‘Niccolò ambles out to the piazza’, ‘Niccolò offers a modest bow’), the biography provides a colourful picture of Renaissance Florence in Machiavelli’s day. The Tuscan city was then officially a republic; however, the Medici manipulated politics and alliances to extend their power in monarchic fashion. Machiavelli soon found himself himself embroiled in the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola’s hellfire preaching against the Medici’s perceived financial and sexual outrages.

According to Benner, Machiavelli was not a supporter of Savonarola’s ‘Christian-flagellant’ vows to purify Florence, but a Savonarolan part of him agreed that Florence had become a virtual police state. Savonarola, Ferrara-born, was especially exercised by Florence’s reputation as a sodomitical hotbed. Much of the greatest art partronised by the Medici (for instance, the blatant musculature of Michelangelo’s ‘David’) was unabashedly homoerotic. In 1497, however, Savonarola was excommunicated and burned in Florence as a heretic after he sought to challenge the authority of papal Rome. Conveniently for Machiavelli, the Medici had by now been forced into exile.

It was as deputy chancellor of the popular new Florentine republic that Machiavelli made his name. Appointed to the position in 1498, he carried out diplomatic missions for the post-Medici Signoria (city government), including one to Cesare Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI. As a diplomat, he learned much about the manipulation of power and how best to counter an autocratic Medici revival. However, the liberty of Florence came to an end 14 years later, in 1512, when Machiavelli was arrested and tortured after the Medici family returned. Soon into his imprisonment, by a miracle, Pope Julius II died and his successor Pope Leo X, Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici, declared a general amnesty for all political prisoners. Afterwards, Machiavelli began to work for the reinstated Medici, writing not only his 1532 political treatise The Prince (opportunistically dedicated to Lorenzo de’ Medici), but also a series of books on the nature of republics and some enduringly funny satirical plays.

Benner, with two academic books on Machiavelli to her name already, has written a most unusual life of the Tuscan thinker-diplomat. Using dialogue freely reconstructed from primary sources, she builds a novelettish picture of love and political intrigue amid merchants of menace and high finance. At times the prose is sub-Jean Plaidy in its breathy overtones (‘he curls up under the sheets on one side, timid and bashful as a virgin wife on her wedding night’); at others, it tries rather too hard to be reader-friendly:

Our great Florentine profiteers are shocked when no one trusts their republic of skinflints, men who’d do anything to dodge long-term commitments to save a few ducats.

Benner, a Yale-educated political theorist, nevertheless makes a decent case for Machiavelli as being less ‘Machiavellian’ than The Prince might suggest. He was, apparently, an ironist, whose views were kept hidden for reasons of political circumspection. ‘If sometimes I do happen to tell the truth,’ he wrote, ‘I hide it among so many lies that it is hard to find.’

All the same, very little that Benner says actually disputes Machiavelli’s reputation as a Renaissance-era pragmatist and testa dura (hard head). The title Be Like the Fox, after all, refers to his advice to be fox-like in politics and thus avoid entrapment. Leave the gun. Take the cannoli.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in