‘What makes the Red Man red?’ the Lost Boys asked in Disney’s Peter Pan (1953). According to Sammy Cahn’s lyric, it was embarrassment: ‘The very first Injun prince/ He kissed a maid and start to blush.’

Redness is everywhere in The Earth is Weeping — in the anger of the Indians, harried and starved into fatal resistance; in the shame of the whites, with their fork-tongued treaties and heavy weapons; and in the blood, Indian and white, that flows on almost every page of Peter Cozzens’s sweeping, expert and appalling account of the murder of America’s Indians.

Every nation has its founding sin. America, the land of plenty, has two. Cozzens’s story begins in the 1860s, with the expiation of slavery and the refounding of the United States, but the commission of murder was already well advanced. In the early decades of European settlement, disease and war had reduced the Indians of the north east. In 1830, Andrew Jackson’s administration passed the Removal Act, pushing the Indians of the old north west and the ‘civilised’ tribes of Alabama and Georgia across the Mississippi and into a swathe of the Great Plains, reserved as Indian territory.

Jackson believed the army explorers who had reported that the Plains were unsuited to white settlement. In the 1840s, American maps showed a permanent Indian frontier, running south from Minnesota to Louisiana. Meanwhile, Cozzens writes, ‘a cataclysmic chain of events’ dissolved the frontier: the rush for land in Oregon and gold in California, and the annexation of Texas, California and the south west. By 1860, there were more whites in California than Indians in the entire west.

There were also more Indians in the Great Plains than ever before. While the whites stripped the land on their way westwards, displaced tribes like the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapohoe fought for the territory of established Plains tribes like the Pawnee and Crow. Inter-tribal feuding was ‘the very foundation’ of the Indians’ warrior culture, and a necessary struggle for the resources it required, especially the buffalo. But it undermined a sense of common ‘Indianness’. Instead of uniting against the whites, the Indians split into ‘accommodationists’ and ‘traditionalists’.

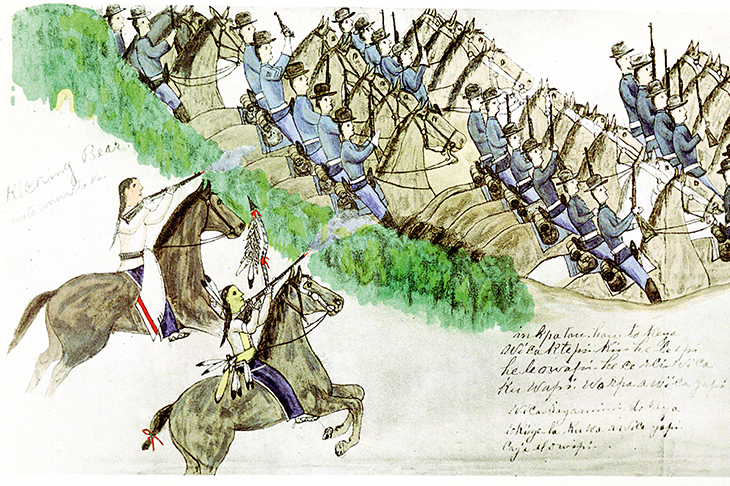

The Indian wars were overlapping civil wars: whites against Indians, and Indians against Indians. Often, the expulsion of Indians by newly arrived whites was the ‘displacement of one immigrant group by another’. The savages were on both sides. The Indians scalped and mutilated their dead enemies, to handicap them in the afterlife. US soldiers responded with rape, murder and dis-embowelment. The Apache were especially feared for their ingenuity as torturers. Cavalrymen often tied their bootlaces to their triggers, and saved their final bullet for themselves.

Yet the Plains were never a level playing field. The Indians were superb horsemen and archers, and the US army had ‘barely enough men to defend its small forts’; but the army adapted its tactics. By 1876, when the vain and untrustworthy George Custer led more than 200 cavalrymen to their deaths at Little Bighorn, the army had learnt not to be drawn out of its encampments, and to surprise the Indians in their winter camps. Meanwhile, Indian warriors raced into the army lines in order to ‘count coup’ — to win prestige by touching an enemy with a ‘coup stick’.

Every Indian victory was pyrrhic, in provoking terrible retribution. Every defiant leader — Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse — surrendered in the end. The federal government failed to help the Indians starving on reservations, but always found the means to punish every Indian revolt. In December 1890, the massacre of Bigfoot and the Lakota Sioux in the snow at Wounded Knee marked the closure of the frontier, and the death of an ancient civilisation.

This murder by ‘grand encirclement and slow strangulation’ was not, Cozzens argues, genocide. The federal governments that reneged on treaties and defrauded the Indians of their land and rights also launched five sets of ‘peace’ talks in the 1860s and 1870s. In 1866, when General Sherman, the head of the US army, advised ‘vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women, and children’ the Grant administration instead pursued peace talks.

Yet when Sherman advanced his solution for the ‘Indian problem’, he was the legal subordinate of the secretary of war. Cozzens writes that ‘the federal government never contemplated genocide’, but this is to acquit on a technicality.

The systematic treachery of the federal government, and the ‘vindictive earnestness’ of the settlers and soldiers, accomplished the murder of the Indians without a policy statement. ‘No matter what’s been written or said / Now you know why the Red Man’s red!’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in