Opera is littered with the bodies of abandoned women. Step over Dido and Gilda, and you’ll still stumble into Donna Elvira, Euridice, Elisabeth, Ariadne, Alcina. The list goes on. Pop music might have ‘50 Ways to Leave Your Lover’, but opera has 500. Call it chauvinism or voyeurism if you like, but opera’s women are at their most powerful in despair, even death. Their anguish might be aestheticised, but it shouts louder and more truthfully than the corpses of the endless female victims of television’s police procedurals, as two arresting performances attested this week.

It’s her feet you notice first. Flexing and arching convulsively, rubbing up against one another as though to scrape flesh from bone. Soprano Anne Sophie Duprels is a consummate singing-actress, and as Elle — the abandoned lover of Poulenc’s one-act monodrama La voix humaine — her sense of entrapment, of finding herself in not just a body but also a situation not her own, was palpable in every gesture. In an opera house it would have been painful; in the close quarters of the Royal Albert Hall’s Elgar Room it was all but unbearable.

Poulenc’s opera has the unblinking quality of an Ian McEwan novel. It’s a piece of emotional reportage that looks coolly on as a woman is stripped, first of control and social convention, then of her self-preserving lies, her dignity, and finally — perhaps — her life. Adapted from Jean Cocteau’s play, it places the unnamed woman alone on the stage, intermittently connected (according to the vagaries of the 1950s French telephone network) to her former lover. His voice is heard only in the musical accompaniment, leaving us to supply, all too easily, the other side of this inevitable conversation.

Set against Duprels’s jagged emotions, punching through the confines of Poulenc’s often contorted phrases, the patrician ease of Pascal Rogé’s accompaniment grated deliciously. If this solo piano version lacks the generous ‘orchestral sensuality’ of the original, it gains in dramatic specificity, leaving nowhere for the easily and ingratiatingly melodic music of the absent lover to hide. Melody, like talk, is cheap — ammunition for a coward’s weapon that ‘leaves no trace and makes no sound’, the telephone.

The sense of musical conspiracy is heightened in the single combat of piano and voice. When Elle recalls the handful of sleeping pills she took the night before, we hear their seductive lure in the piano’s lulling accompaniment. When she lets her mind drift to nights spent in bed with her lover, it’s the piano that spins the seductive reverie. Parasite-like, it gains rhapsodic strength even as Elle herself drains away to silence.

With two such performers and such a small space, all director Marie Lambert had to do was keep out of the way. This she didn’t quite manage, cluttering the stage with objects whose heavy symbolism jarred against the meticulous honesty of Duprels’s emotional vivisection, their meaning as obvious as the primary colours in which they were painted. But it was a misstep that mattered little once it became clear that the real stage space here was a body, a voice, and nothing more.

It’s very easy to emerge from a performance of Madama Butterfly having had a good time. Puccini is at his intoxicating, tune-filled best, and heavy drapes of orchestration contrive to veil the story for what it really is. The cynical exploitation of the 15-year-old Butterfly as a sexual plaything for western amusement, and her subsequent abandonment, is one of opera’s most grotesque plots, but it takes a rare performer to remind us of that. It’s testimony to the dramatic generosity of Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho’s Butterfly that, for once, we are allowed to see the bloodied dagger hidden beneath embroidered kimono silks and tumbling cherry blossom.

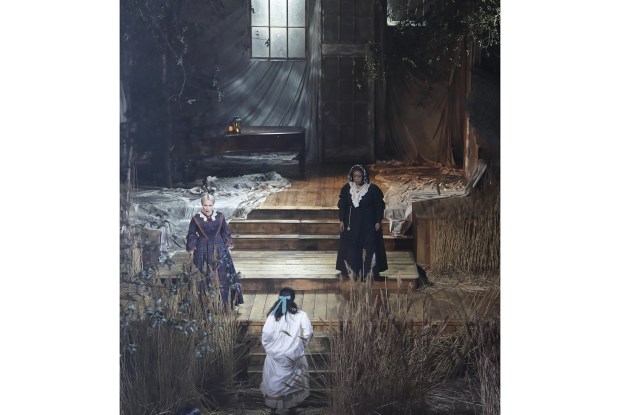

Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier’s 2003 production is all functional traditionalism — a flat-pack Japan where morals slide along with doors and walls. Into this mass-produced frame they add a few requisite touches of sentimentality (Butterfly’s kimono sleeves too often invoke the wings of her namesake, love transforms black-and-white landscapes into gaudy technicolour) and everyone goes home happy. But with Jaho we have a Butterfly that can bear the close-up of the HD cinema camera, whose gaze has made better productions blush. This Butterfly seems to know from the start that she’ll only live for a day — wants her love story to be true more than she knows it — as she pleads with Marcelo Puente’s Pinkerton to ‘Love me, just a little’.

Jaho’s chameleon quality extends to a voice that, while still on the lighter side for the role, finds such weight of emotional colour. Denied a very satisfying lover in Puente’s granular tenor, she finds her equal instead in Elizabeth DeShong’s radiant Suzuki (a shamefully belated house debut), whose tone hangs velvet-heavy from her melodies. Together the two women break your heart again and again, but you won’t want them to stop.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in