Southern trees bear a strange fruit in Laird Hunt’s seventh novel, a dark historical fiction filled with dreams and visions that has one very disconcerting trick of style to play on the reader. The setting is Indiana in 1930, where a white woman called Ottie Lee Henshaw is on the way to a lynching in the town of Marvel with her lecherous boss Bud and her redneck husband Dale. They stop to feed Dale’s pig; they stop at a church supper and a Quaker prayer meeting; they stop at a backwoods still; they stop to forcibly relieve a black family of their buggy. They meet a Klansman, an elderly acrobat and a man on a bicycle. They never make it to Marvel, because this is a book about journeys, not destinations. Instead, as she travels through the hot night, Ottie Lee sinks back into her own troubled dreams and memories. She has been told there is something special coming, and she has a special map in her hand that will get her to ‘Marvel and its marvels’. ‘Who knew what fearsome wonders would populate the night,’ she wonders, ‘who knew how long it would all go on?’

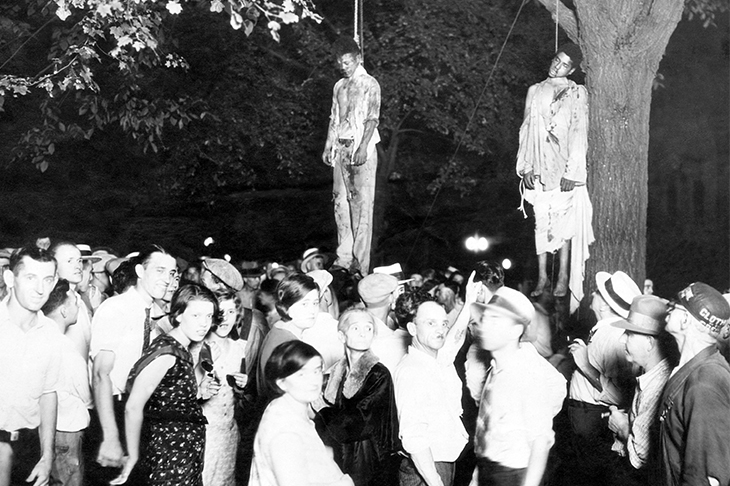

The second part of the book follows a black woman, Calla Destry, who is travelling in the opposite direction, from Marvel — a place that is meant to remind the reader of Marion, Indiana, where two black men were taken from a prison and murdered by a white crowd in 1930. Recorded in a notorious photograph, that lynching is also the event to which the song ‘Strange Fruit’ refers, and Hunt has drawn on an account by James Cameron, who survived it, in writing his novel.

Calla Destry is a furious avenger — ‘Wrong wasn’t the word for what was happening. It was 1,000 miles from what needed saying’ — and she carries an instrument of vengeance hidden in her basket. Her story is more eventful than Ottie Lee’s, but her voice is more prosaic, less strange and compelling: is Hunt more wary of inhabiting the head of a black protagonist, or does the second section simply have too much narrative heavy lifting to do? At some stage, anyway, the paths of the two protagonists will cross.

Most noticeable throughout is Hunt’s unusual decision to replace the charged vocabulary of segregationist insult and aggression with a set of coinages all his own. White people are ‘cornsilks’, black people are ‘cornflowers’, Chinese people are ‘corntassels’ and Native Americans are ‘cornroots’; but the reader is left to parse their various identities in sentences such as ‘He had stories he didn’t like to tell about cornflowers and corntassels and cornroots running low on gas when they were out in cornsilk country’.

How this goes down will depend on the reader’s sense of what a writer owes to the historical record, though I felt it added to the mesmeric, underwater feeling of Hunt’s prose. Drift and mood are everything in this weird book; it goes nowhere with particular vigour, but its eddies are often worth lingering in.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in