This book, according to its author Gabi Martínez, is ‘a non-fiction novel’. It tells the story of Jordi Magraner, a Morocco-born Spaniard who grew up in France. A largely self-taught zoologist and naturalist, Magraner worked on humanitarian convoys in Afghanistan before devoting his life to searching for the Yeti among the Kalash people in the Hindu Kush. He was, according to Martínez, ‘Proud. Enigmatic. Multifarious. Pagan. Passionate. A beast.’ The book opens with his murder (which remains unsolved).

The Yeti, possibly a version of Neanderthal man, are the monsters of the title. In north Pakistan they are known as barmanu. These bipeds never make an appearance. But Magraner kept the faith. He put together a dossier on ‘relict hominids’, and made a study of the cranial bone, and was at one point invited to lecture on the topic in Cambridge. The book includes boring details of the politics of ‘the Neo-Darwinists who run French scientific institutions’.

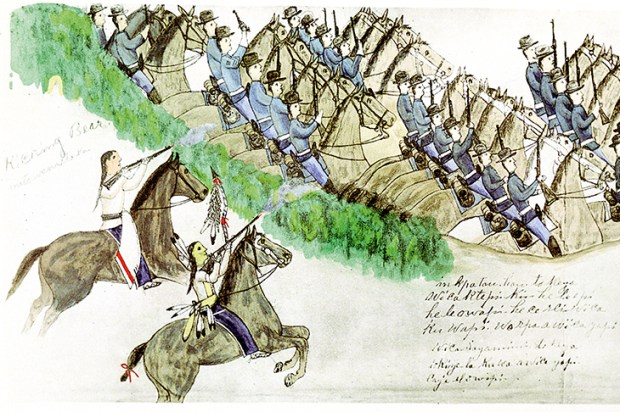

Martínez is a prolific author in his native Spain of both fiction and non-fiction. First published in Spanish in 2011, and fluently translated here by Daniel Hahn, In the Land of Giants benefits from the author’s access to Magraner’s diaries and letters, and to photographs, which appear in the book.

Magraner first went to the valleys of north Pakistan in 1987. He semi-adopted two boys, one of whom, a Nuristani, shared his bedroom. When this latter child showed a reluctance to go to school, Magraner hit him. At this point in the story one loses all sympathy for its subject, and to a certain extent, all interest in him. He went on to have other fist fights; at one point, putting words into his protagonist’s mouth, Martínez describes an Afghan whom Magraner beat up as ‘that loathsome sack of shit’. Very nice.

Magraner lost his job at the Alliance Française in Peshawar, the nearest city to his base at Chitral in the valleys, over allegations of paedophilia. Martínez is not judgmental. ‘He had found in Pakistan,’ he writes of the Yeti-hunter, ‘a place where he could live as he wanted, free to enjoy nature, his profession, his sexuality. ‘

I would have liked a bit more on the pagan Kalash, an ancient people who have whiter skins than the Muslims who live around Chitral. Martínez claims that Magraner wanted to ‘rescue’ the Kalash. At any rate, he founded a group for the study and safeguarding of the cultures of the Hindu Kush. The nascent Taliban float in and out of the picture, and more on regional politics would have been welcome too.

Echoes sound through these pages of the hopeless idealism of Chris McCandless, the subject of Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild, and of Tim Treadwell, eaten by the grizzly bears he championed in Alaska and the subject of a documentary by Werner Herzog. We are told that Magraner ‘yearned to spread a kind of purity, a truth so clean and faultless that it would distinguish him somehow’.

The authorities in Chitral had advised him to leave the valleys months before his death in 2002, ‘because his life was in peril’. Some saw the search for the mythical barmanu as a front for espionage. It is still unclear whether his murder (he was stabbed) was political or a crime of passion.

Martínez ably conjures the scent of juniper, the taste of black, salty tea and the sight of a 40-donkey convoy heading to Panjshir. As well as slabs of invented conservation, there are discussions about the characteristics of a monster, whether animal or human. Throughout, the author is preoccupied with Magraner’s inner life, constantly trying to prove the man’s brilliance. But it doesn’t work. Magraner emerges as an unpleasant freak. ‘His life is a metaphor for many people’s lives,’ Martínez pronounces. Is it?

The author enters the story himself in his quest for the truth, visiting the Hindu Kush and interviewing everyone there, as well as Magraner’s family in France, whose confidence he gains. He is a diligent researcher. His own journey takes over towards the end, as he searches for clues: ‘Just like Jordi was seeking the Yeti, so I am seeking Jordi. We are a dream of chains and hopes. Where will it end?’ Where indeed?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in