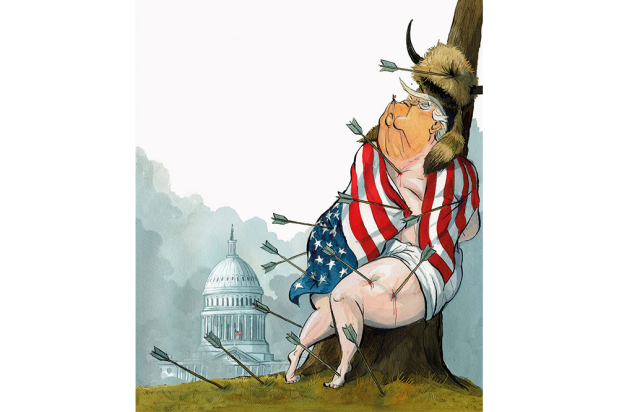

Howard Jacobson awoke to the news of Trump’s victory in November. He had no newspaper column so, what could he do? Write a novel, said his wife, and he did, in six weeks. It is called Pussy, and it is a short and horrifying hypothetical biography of Donald Trump, now an infant prince called Fracassus, born into a noble family of property developers. Fracassus hates words. He hates women. He tweets. Jacobson throws every weapon — every word — he has into Pussy. He is the voice of the metropolitan liberal elite emitting a death rattle, and that is a grave calling.

I have loved Jacobson since he wrote this, in 2011, about the ‘new’ anti–Semitism: ‘Thus are Jews doubly damned: to the Holocaust itself and to the moral wasteland of having found no humanising redemption in its horrors.’ If I love his journalism, I cannot finish his novels because — and this is a very Jewish criticism — they are too evocative. Reading The Finkler Question — for which he won the Booker Prize in 2010 — made me want to hit my father with a spade.

In person, Jacobson isn’t noisy. His novels, which he ‘stole from his own life’ take it all, and leave him courteous and calm — except when he is talking about Trump, ‘the’ social media and Brexit. He is 75, but he looks younger. He speaks in a low Mancunian growl.

Jacobson is a child of two warring Jewish worlds, which make, by my count, three civilisations to be torn between, and the potential for three separate alienations. He has mined them all. ‘We are all our parents’ battlegrounds,’ he says. ‘Mine was very stark because my dad was unlettered, extraverted, vivacious.’ His father’s family were Ukrainian Jews: ‘The rabbis who did somersaults, the charismatics.’ He was a market trader, and a children’s magician: ‘Not a very good magician. The kids could see.’ His mother’s family were Lithuanian Jews: ‘Scientists, philosophers, students. They were shy, easily hurt, [and] withdrew into themselves. At family dos, the hokey cokey would come around and my father’s sisters would be screaming and my mother and her sister were shrunken in a corner.’ In 1961, he left grammar school for Downing College, Cambridge, to study under F.R. Leavis.

He was terribly shy: ‘I didn’t know how to make anything work for myself.’ He was self-destructive — or angry — enough to write a ‘violent, sexually deranged’ essay for Cambridge’s leading pacifist intellectual, and graduated with a 2:2; the neurotic’s degree.

‘Cambridge played into some of my own peculiar paranoia,’ he says now. ‘Something happens. Like Rip Van Winkle, I fall asleep, and then when I wake up everything has changed and I have got to catch up again. I always have that sense. If I go into any room and everybody knows one another and I don’t know them and they don’t know me.’

In his twenties he lived with wife, his baby, and his parents-in-law; he taught in a secondary school; he sold leather goods in Cambridge market. ‘I felt I had gone backwards,’ he says. So he left: ‘I took my little boy to school one morning and said, “Daddy won’t see you for a little while”, and flew to Australia to be with my friends.’

He was, he says, ‘very selfish and unhappy and an unhappy man is very dangerous’. He returned to a job at Wolverhampton Polytechnic, and despair. ‘My dad used to tease me, people would jeer at me because I called myself a novelist. I just did not know what to do, I couldn’t find it, I couldn’t find a voice.’ In the opening of Kalooki Nights — ‘the best thing I have ever written’ — he writes an equation about Jewishness. J÷J=j. But he can’t solve the equation. He can’t minimise the J and, in his heart, he doesn’t want to. So he wrote Coming from Behind, the story of Sefton Goldberg, a Jewish lecturer who sounds like Howard Jacobson, at a polytechnic that sounds like Wolverhampton Polytechnic.

‘The voice needed to have Jew in it,’ he says. ‘That’s the only way to explain your life so far: why you felt out of place, why you felt that the culture that you belong to doesn’t think you belong to it.’ He knew this now. ‘Finally, finally, a novel,’ he pauses, ‘with my name on it.’ He was 41.

Writing, he says, was ‘a liberation from what I was — the limitations of who I was —and the life I was living. I could retell me. I could retell the story of the world — that is to say, my world. I could make me again.’ He is very emphatic. ‘That was the way to somehow get out. There was some truth that needed to be told, and only I could tell it and I had to tell it my way. Until I did it, everything else was incomplete.’

And that is why he wrote Pussy, in a frenzy of bewilderment and disgust. It is a defence of everything he has loved; and everything that has saved him. He cannot understand why everyone does not like his novels: ‘So who is not going to like it?’ And he cannot understand how someone can be as stupid — so happily, proudly stupid — as Donald Trump.

‘How do you put your shoes on in the morning? How do you exist and be so dumb?’ He read The Art of the Deal. He ordered it from Amazon. ‘I could write it in about a minute,’ he rants. ‘The dog could write it. It is the emptiest mind there’s ever been!’ So he imagined a hinterland for the infant Donald and it is the emptiest place you could imagine.

He doesn’t care about the politics, but ‘the wordlessness of Trump, the wordlessness of the man, and that wordlessness is attractive. That I cannot conceive. When I was a little boy, words,’ and he pauses, to repeat it, ‘words, words were everything’.

He hates ‘the social media’ and its contempt for words. ‘It will be where everything that the Enlightenment has been for, everything that we have tried to aspire to as human beings, out of the primeval soup, grunting for words, finding expression, finding the ways in which we can understand one another through language: gone.’ He says this very low, and adds: ‘Dead.’

He writes to defend his calling, then; he writes to find order. If he writes too much in one day, he says, he will, ‘go to bed early and get up early feeling I have to get rid of it. Because I might die and there is evidence in the world of my having gabbled’.

He thinks about death a lot, particularly when he is happy. But that is the J again.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in