When Stravinsky visited David Jones in his cold Harrow bedsit, he came away saying, ‘I have been in the presence of a holy man.’ Other admirers included T.S. Eliot (his publisher) and the Queen Mother (who wrote asking if she could buy some of his work). Harold Bloom, Kenneth Clark and W.H. Auden were all not merely admirers, but passionate in their admiration. Auden thought Jones’s long Eucharistic poem ‘The Anathemata’ the ‘finest long poem written in English this century’.

Yet Jones remained completely his own man, belonging to no ‘set’. He had very little money and has never, as far as one can tell, been part of the Eng. lit. mainstream. While ‘first world war poets’ on the BBC still seem to be Wilfred Owen and Rupert Brooke, Jones’s In Parenthesis — the greatest war poem in the English language — remains a cult book read by the few.

As a visual artist, likewise, Jones does not have the blowsy splashy fame that has been bestowed on the far less interesting Francis Bacon. Yet the comparisons made, during his lifetime, by many who knew and loved him or his work, between Jones and William Blake, seem entirely apposite. Like Blake, Jones was someone who decidedly followed his own path, even though this entailed a life of poverty and obscurity. His wonderful watercolours and etchings; his haunting arrangements of lettering; his all too few essays on art, literature, anthropology and religion; and his extended poems — meditations on our collective past, mythic, Celtic and Roman — are comparable to Blake’s. He is not derivative of Blake but, like the earlier artist, Jones’s ‘take’ on life and history, completely original, needed the outlet not only of the written word, but of the crafted calligraphic letter and the visual image.

Thomas Dilworth’s biography is the work of a lifetime. It has been worth waiting for. He tells us at the end that the present book is ‘a condensation of a much longer document which will eventually be a public website’. Sometimes one can see the wounds where a publisher’s cut has been made in Dilworth’s narrative, and I rather hope (some hope!) that Jonathan Cape will issue a collector’s edition of the fuller text. Once bitten by the Jones enthusiasm, the reader will find everything of interest. No detail is too trivial.

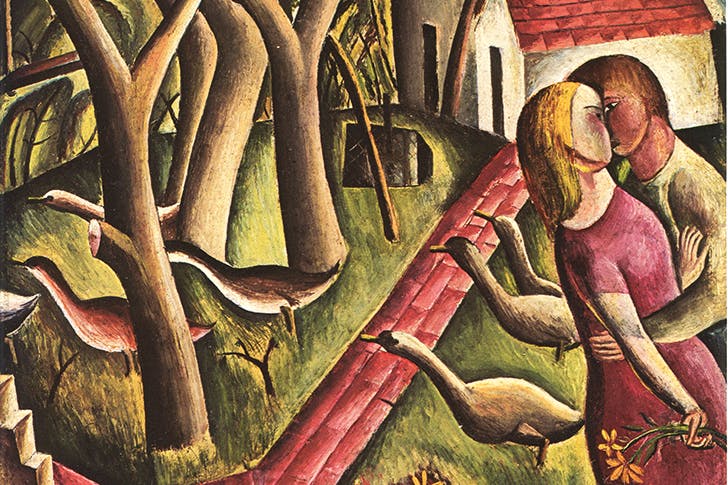

‘The Garden Enclosed’ from the 1920s, when Jones was still influenced by Eric Gill

‘The Garden Enclosed’ from the 1920s, when Jones was still influenced by Eric Gill

The basic outline of the life was well-known before this book. Jones was born in Brockley, on 1 November 1895, to lower-middle-class parents, his mother a Cockney, his father Welsh. It was a religious household — funnily enough not Welsh Chapel, but low C of E. When the first world war broke out, he enlisted in the London Welsh Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers, aged 18 — at 5’ 71/2” he had not yet finished growing. Of his experiences on the Western Front Dilworth writes:

Every July for the rest of his life he would relive the experience of the Somme, saying, in 1971, ‘my mind can’t be rid of it’.

Later in life, when he had suffered a debilitating breakdown — ‘my old nerve thing’ as he called it — a Freudian psychiatrist diagnosed his troubles going back to ‘fear repressed in the trenches’. (To an earlier shrink, to whom he had been sent, Jones remarked, ‘You’re not going to make me normal, are you, because I don’t want to be.’) Panic attacks, agoraphobia and social inadequacy confined him, for many of his 79 years, to a life indoors. William A.H. Stevenson, the Freudian who did become Jones’s regular shrink, wondered whether he was a repressed homosexual; but this was clearly not the case, and the succession of crushes he had on beautiful women — passions which did not go anywhere — seems to have been an essential ingredient in his art.

After art school, where he was taught by Sickert, Jones became a Catholic and joined Eric Gill’s Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic at Ditchling. He was engaged for a while to Gill’s daughter Petra. Gill — nowadays almost more famous for his erotic life than for his art — deemed Jones ‘the most highly-sexed man he had ever known and regarded his chastity as a marvellous spiritual achievement’. One wonders how it is possible to judge how highly sexed another person is, especially as, in Jones’s case, the only recorded erotic moments in this book are walks on the Sussex Downs with Petra, in which ‘they enjoyed the pleasures of mutual masturbation’.

He stayed with Gill’s Guild for a while after Petra’s marriage to the former Trappist monk Denis Tegetmeier in 1930, but Jones was never completely taken in by Gill’s posturings. He cut loose from it, and in some ways his art took off when he left Gill and turned to the subtler and more benign patronage of Jim Ede (he of Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge).

Apart from his great skill in expounding the poetry, and his intuitive knowledge and love of the visual art, Dilworth is memorably intelligent and sensitive in describing Jones’s many intense and emotional relationships with women. Particularly touching are two. Prudence Pelham, a tall, beautiful upper-class girl who had come to Ditchling to learn carving, completely captured his heart. But although she was happy to be his muse, and they were soulmates, reading aloud to one another from Finnegans Wake, she rejected his physical advances. Her marriage broke his heart, and her end, with multiple sclerosis, was awful. A much later passion was for Valerie Price, a beautiful Welsh nationalist, nearly 40 years his junior, who worked in the personnel department of a London chemical engineering firm. She does seem to have cuddled him, but the relationship followed the pattern of all the others — passionate devotion on his side, ending with her marriage to someone else, and his heartbreak.

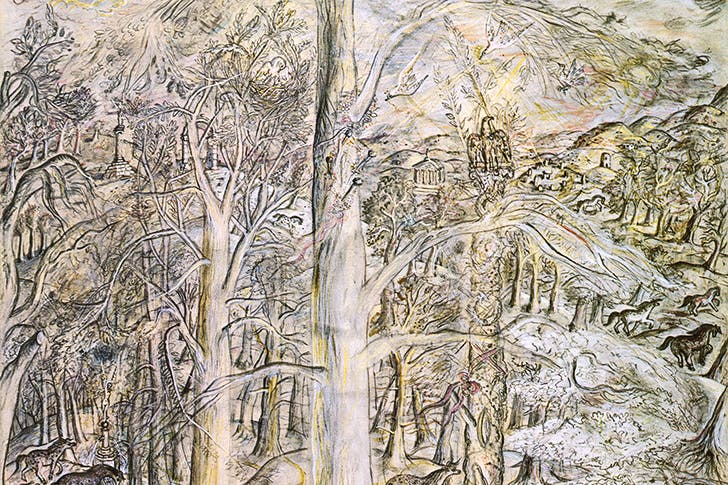

The subtler ‘Vexilla Regis’ was painted in 1948

The subtler ‘Vexilla Regis’ was painted in 1948

Dilworth is deft at tracing two of the essential ingredients in Jones’s life and work. One is the way that his poetry — original and strange as it seems on the page — often came to him, as it were, ready-made. A mainstream and famous example occurred in a communication trench in March 1917 when he encountered one Evan Evans, the shit wallah from a Welsh battalion. Seeing Evans stagger along with his full buckets, Jones remarked, ‘You’ve got a dirty bloody job.’ ‘Bloody job indeed,’ Evans replied. ‘The army of Artaxerxes was utterly destroyed for lack of sanitation.’ Thus was Jones’s ‘Dai Overcoat’ born. Jones’s sense that war was archetypal, the soldiers in the trenches revisiting and re-presenting the experiences of the Roman legionaries who attended the Crucifixion or the Welsh warriors, ‘helmeted like their ancestors at Agincourt’ — was not something that he invented; it was really there. (One thinks, in a comparable context, of Gwatkin, the Welsh bank manager in Anthony Powell’s great sequence, identifying with the legionaries in Kipling.)

The other ingredient in the story, once Jones had found his spiritual home, is the texture of Catholic life in England between the wars. Dilworth evokes what a small world it was, Jones numbering among his friends Vicky Ingrams, Hugh and Antonia Fraser, Julian Oxford, Martin D’Arcy and

Evelyn Waugh. Jebbs, Pollens, Burnses, Woodruffs and Actons abound, many of them slipping the impoverished Jones cigarettes, whisky and cheques. The pen sketches of many of these characters are masterly. I liked the story of Evelyn Waugh telling Jones that his fringe of hair made him ‘look like a bloody artist’. ‘I am a bloody artist,’ Jones replied. That really is the story of this wonderful book.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in