What will we do when there are no longer caches of letters to piece together and decipher; only vague memories of myriad emails? We will be like butterfly hunters flailing around with our nets, hoping to catch some rare specimen with glittering wings among the detritus of daily exchanges. The letters of Ida Nettleship, first wife of the arch-bohemian Augustus John, are a case in point: gathered together here from diverse sources by her granddaughter Rebecca John and expertly introduced by John’s biographer Michael Holroyd, they constitute a rare epistolary treasure trove.

Spanning some 15 years, from Ida’s late teens to her early death from puerperal fever at 30, following the birth of her fifth son, they give us a startlingly vivid picture of what it was like to be bound by passion, loyalty and an ever-growing brood of offspring to a ‘genius’, whose rampant sexuality and over-arching egotism were altogether at odds with conventional notions of marriage.

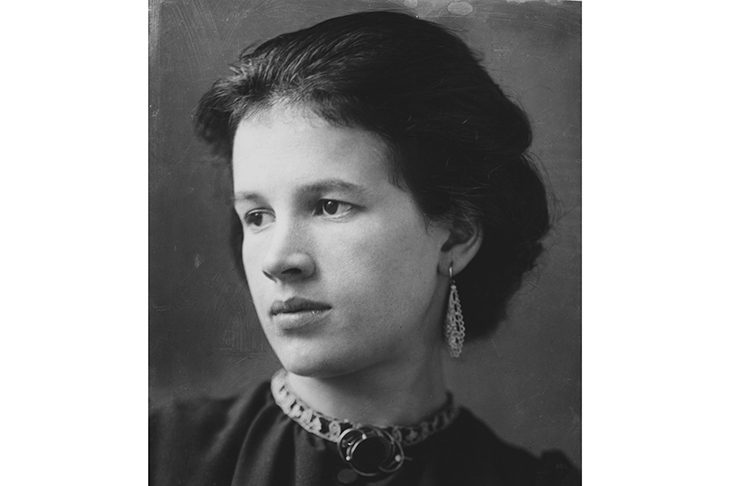

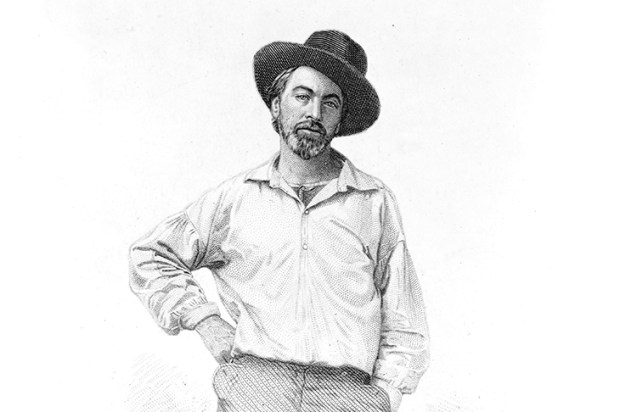

Ida, herself the daughter of a ‘once celebrated’ painter, Jack Nettleship, went to the Slade at the age of 15 in 1892, and caught Augustus John’s eye towards the end of her six years there. She was already an enthusiastic correspondent, firing off teasing and somewhat arch letters to her sisters and beloved friends from the Slade, notably the Salaman sisters, to whose eligible brother Clement she would briefly be engaged. But once Augustus turned up, Clement stood no chance; the engagement was swiftly broken off in favour of the magnetic artist who wore earrings, often dressed like a tramp and kept company with gypsies and tinkers. Ada Nettleship, a quintessential Victorian matriarch, was appalled, and the couple stole away to be married privately. The extent to which Ada’s forebodings would be played out on the marital stage is the essence of this absorbing book.

Extracts from Ida’s letters were of course included by Holroyd in his celebrated biography of John, but here Ida, not Augustus, is centre-stage; hers are the eyes through which we see the story unfold. This turns the triangle on its side, and gives us an altogether different line of vision. For a triangle it became, with the arrival in 1903 of the sphinx-like Dorelia McNeill, a figure even more magnetic than John: certainly Augustus’s sister Gwen, ever inscrutable, was obsessed with Dorelia and spent many months travelling with her through France, painting, modelling and sleeping under haystacks. Augustus could not conceal his passion for her, and even Ida fell under her spell, imploring Dorelia to come and live with them in rural Essex, knowing full well that John could not, and would not, live without his muse. It was torment; yet she loved Dorelia too and appreciated her qualities. Clear-eyed, she wrote to her:

You are the one outside who calls the man to apparent freedom & wild rocks & wind & air — & I am the one inside who says come to dinner & whom to live with is apparent slavery.

By this stage, Ida was the mother of two sons, David and Caspar, and pregnant with her third child; she was often lonely with ‘Gus’ away, had no time for painting, was desperately paddling to keep her head above water, and suffered bouts of depression and exhaustion. No freedom for her, yet her letters to friends remain bravely bright; only to her beloved Mary Dowdall does she confess:

This house is pokey, and I live the life of a lady slavey – but I wouldn’t change — because of Augustus — c’est un homme pour qui mourir — and literally sometimes I am inclined to kill myself.

And later, ‘I am surrounded by cows and vulgarity here. Isn’t it awful when even the desire to live forsakes one?’ Gus appeared and disappeared like the Cheshire cat; among the illustrations is a wonderful photo of him playing the concertina in bed, cigarette dangling, every inch the bohemian.

And there’s the rub: how ‘good’ a bohemian did Ida manage to be? She mastered her jealousy, gazed reality in the face, and shrugged off the disapproval of friends and family at her ongoing ménage à trois. Eventually, throwing any shreds of convention to the winds, she and Dorelia bunked off to Paris together with their children, leaving Augustus behind: they would look after one another better that way.

It was the truth that she embraced, squarely and with spirit, and the fine balance between tragedy and comedy in her situation finds expression in letters so fresh that it is hard to believe they were written more than a century ago.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in