The history of modern medicine is a roll call of brilliant minds making breakthrough discoveries. We rarely hear about the losers, but Wendy Moore has chosen to write the extraordinary story of a massive medical fiasco: the craze for mesmerism which gripped Victorian London in 1838.

The practice of using the ancient technique of hypnosis for medical purposes takes its name from the 18th-century German physician Franz Mesmer. The mesmerist of Moore’s story was a society doctor called John Elliotson, a man who has been almost forgotten today.

Elliotson was a self-made physician who rose quickly to the top of his profession. Clever, tough and ambitious, by the age of 40 he was professor of medicine at London University. He was instrumental in founding the North London Hospital (later UCH) for the London poor. A brilliant lecturer, he campaigned to break the hold of the self-selected oligarchy which ruled the medical establishment. He championed new discoveries, such as quinine and the stethoscope, and the understanding of allergies, such as hay fever; and he introduced real improvements in hospital practice. He was drawn to mesmerism as a cure for epilepsy but, as Moore clearly shows, he soon became fanatical about it.

Elliotson’s subject was a 17-year-old working-class London girl named Elizabeth Okey, who supposedly suffered from epilepsy. When he hypnotised her, she fell into a trance and then began to perform strange antics. She talked, opened her eyes and behaved in a uninhibited way. Her personality completely changed. Normally shy and demure, Elizabeth flirted and joked and appeared not to feel electric shocks.

Elliotson’s séances at UCH were public performances, and people flocked to watch Elizabeth. Dickens was entranced by her. Elliotson was a man obsessed. He mesmerised Elizabeth several times a day for many months. As her behaviour became ever more barmy and outlandish, the doctor-patient dynamic shifted. Increasingly, it was Elizabeth who called the tune, telling Elliotson to leave her alone and predicting what she would do next. ‘I never saw such a d—d fool in all my life,’ she declared. She advised Elliotson how to treat her and went on ward rounds diagnosing the other patients. Stranger still, her younger sister Jane, also an epileptic, was mesmerised and replicated Elizabeth’s behaviour even when apart from her.

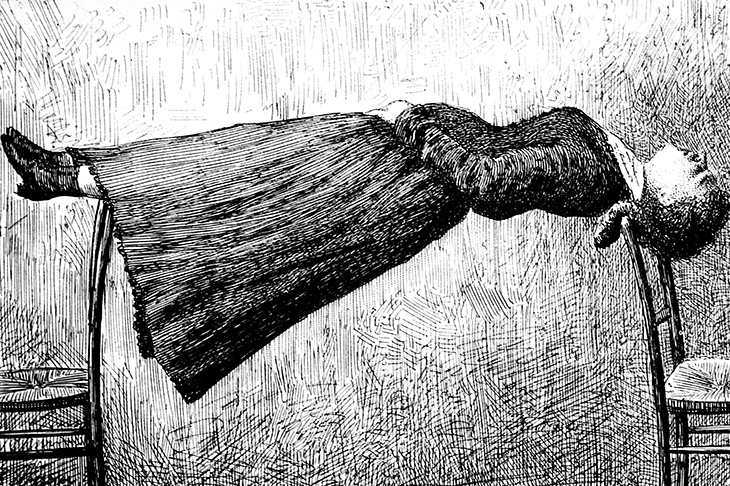

To the Victorian medical establishment Elliotson’s relationship with the Okey sisters was deeply unsettling. The role reversal between physician and patient was bad enough, subverting as it did the professional and social authority of the doctor. Worse still, Elliotson had become an impresario, breaking all the rules of medical research. His séances were not scientific demonstrations but freak shows. The constant performances made Elizabeth very ill — she was delirious for the most of the time when she wasn’t mesmerised — but Elliotson ignored her worsening condition. So credulous was he that it seems never to have occurred to him that she might be acting.

His nemesis was his friend and colleague Thomas Wakley, the founder editor of the Lancet. After performing tests which purported to prove that Elizabeth Okey was faking (actually the tests did no such thing), Wakley published a vicious attack in the Lancet, denouncing the sisters as fraudulent actors. Elliotson stubbornly refused to admit he was wrong. The last straw came when the Okeys walked round the wards at UCH predicting which patients were about to die. Their prophecies came true. The sisters were expelled, mesmerism was banned and Elliotson was forced to resign from the hospital he had founded.

What was really going on with the Okey sisters is still unclear. It’s possible that they were deliberately acting, but this is only part of the story. Moore speculates that at first the mesmeric trances were genuine. But as they were urged on by Elliotson the sisters subconsciously tried to ‘please’ him by more and more bizarre antics. Remarkably, they survived all this and went on to live normal lives.

Elliotson was destroyed by professional jealousies and his own stubbornness, and his fall discredited mesmerism as a therapy. Outside the public hospitals, however, provincial doctors continued to practise it. It gained traction as way of dulling pain, and doctors performed operations using it as an anaesthetic. But it was no competition for the new chemical anaesthetic drug of chloroform which, unlike mesmerism, put the doctor firmly in control of the patient.

Wendy Moore is an expert guide to the world of early 19th-century medicine, and this fascinating book is packed with buccaneering, larger-than-life doctors and gruesome operations, as well as the minutely documented antics of the Okey sisters. UCH in those times was evidently a much livelier place than it is today under our dear old NHS.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in