Donald Winnicott once told a colleague that Tolstoy had been perversely wrong to write that happy families were all alike while every unhappy family was unhappy in its own way. It is illness, Winnicott said, that could be dull and repetitive, while in health there is infinite variety.

Winnicott was reared in an environment of plain-speaking west-country Methodism. He was a people’s doctor who earned his spurs in the crowded children’s wards of east London’s wartime hospitals, allergic to dogma and fearless of being labelled a heretic. He believed that mothers did not need experts to tell them how to care for their own babies and, equally, that artists didn’t need to be justified or understood by psychoanalysts.

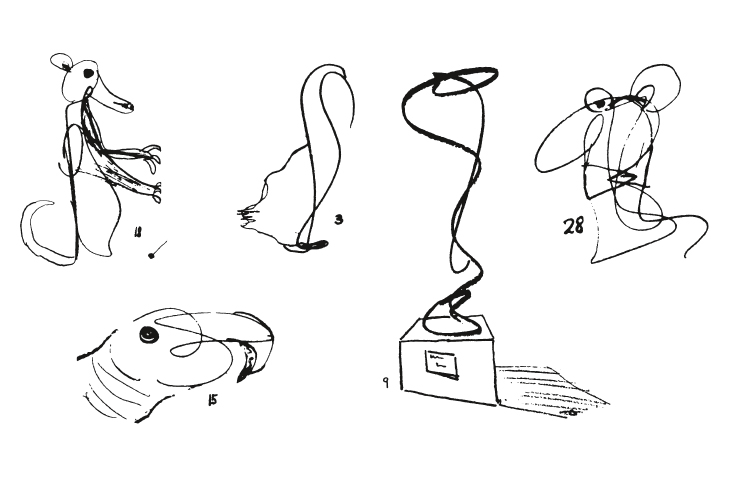

Yet Winnicott — the great psychoanalyst — made creativity, spontaneity and playfulness the sine qua non of his life and work. He and his wife Claire, an influential child social worker and analyst in her own right, would hand draw or paint their own Christmas cards each year to send to their friends. He filled his letters with witticisms and drawings, and regularly doodled, rather than wrote, his signature. Some examples of this can be seen for the first time in OUP’s new Collected Works of D.W. Winnicott.

Winnicott’s writings on the place of creativity in health and illness were subtle and balanced; he was not interested in using psychology to analyse an artwork as if it could be read as a symptom.

To think about the phenomenon of creativity, of being able to create something out of our imagination, Winnicott takes us right back to the beginning to examine our very first phase of life. The newborn baby has no conception of the outside world; he is not a philosopher with theories about what the world is or whether it exists. All the baby experiences, hopefully, is that when he is hungry, he can eat, or when he feels cold, he becomes warm. Milk and blankets come as if out of nowhere in response to his feeling a need. He doesn’t know what they are or where they come from. Without any external framework yet and with nothing to work with but his own experiences, for a short time the baby seems to have the power to create the world as he would wish it. It is almost as if he and his hunger ‘imagine’ the milk into existence.

Shortly, the baby will find that there is more to it than his own imagination, that feeding is not just a private experience, that there is a world out there to be found and frustrated by. In this period of adjustment he has the paradoxical feeling that he has both found and created the objects around him. His experiences are in a hazy intermediate area, between inner self and outer reality. Here the first seeds of creativity — to make something using only the imagination — are planted. In the first feeds the baby is using his imagination to create the world, albeit with stabilisers on, as the world is in reality already there providing for him: he is therefore ‘playing’ at creating. Winnicott called this intermediate area of simultaneous discovery and creation a ‘potential space’, in which the phenomena of culture and creativity will occur. ‘This intermediate area of experiencing,’ he wrote, ‘expands into creative living and into the whole cultural life of man.’ Above all, for Winnicott, our ‘potential space’ was a space for playing.

Winnicott was not an artist, but a natural and spontaneous doodler, and he developed a simple drawing game — the squiggle game — to communicate with children during psychiatric consultations. Hesitant that it would be used as a rule-based technique, or even as a test to judge the child, he described what he liked to do in the simplest terms: ‘First I take some paper and tear the sheets in half, giving the impression that it is not frantically important. I say, “This game that I like playing has no rules. I just take my pencil and go like that…”, and I probably screw up my eyes and do a squiggle blind. I go on and say, “You show me if that looks like anything to you or if you can make it into anything, and afterwards you do the same for me and I will see if I can make something of yours.”’

With the squiggle game, the therapist does not need to interpret the child’s imagination or come up with ‘clever’ ideas about what the child is ‘really’ thinking; it is, rather, the child who teaches the therapist about what they have to say. A squiggle can be made into a drawing of a hat or an animal according to the imagination of the child. But, for Winnicott, the act of squiggling is also transformative: a form of communication that could be meaningful or meaningless, revelatory or concealing. Artistic motivation, for Winnicott, was in this tension between the desire to communicate, and the desire to hide.

Winnicott also noted that boys often liked to compete for points, with a winner and a loser. For others, squiggling could be a challenge, bringing out laziness or fear, or being related, in its wilful abandon, to incontinence. Deliberately making a mess on a page was ‘mad unless done by a sane person’, and the element of ‘madness’ is an unavoidable aspect of normal creativity.

In one of his published consultations, with a nine-year old boy known as Charles, the child divulged his fear of an overwhelming chaos that could not be contained. One of Charles’s squiggles had been a frantic scribble, obliterating the page. Winnicott responded by enclosing the mass in a circle and calling it a plate of spaghetti. Charles imaginatively and humorously responded later in the session when Winnicott gave him an equally muddled squiggle; Charles drew a plinth under it and called it modern art.

One of Winnicott’s own later drawings was clearly inspired by the young boy’s sense of humour: he placed a squiggle similar to Charles’s drawing — resembling a sketch of a Henry Moore — on a plinth, and gave it the title ‘Frustrated Sculpture (wanted to be an ordinary thing)’.

To champion the value of a throwaway squiggle is the creative equivalent of Winnicott’s down-to-earth generosity of spirit in his therapeutic practice. He is famous for supporting what he called the ‘good-enough mother’, a phrase intended to describe ordinary devotion, ordinary care, ordinary mistakes, to lighten the pressure on parents to be perfect without sentimentalising what they have to do. The creative gesture, too, is ‘good-enough’, and a child’s or adult’s playfulness has no need to be precociously elevated to a category of artistry to which it does not belong. Children are often blocked or frustrated in their wish to create something so special or unique that they are fearful of failure and cannot finish it; or the intimidating, unspoilt perfection of the blank canvas, and the lure of laziness, might demand that they do not even start. In both cases, in the words of Petrarch, desire outruns performance. What could have been just play has been fatally considered Art. Winnicott would surely have agreed that the most creative component of impersonal corporate sculptures is the graffiti added to them by rebellious and impulsive teenagers.

Winnicott published a huge number of his patients’ squiggles, typically reproducing every one in each consultation. The cases are brought alive by the inclusion of the squiggles, allowing the reader to follow the children themselves, step by step, in their own development of their ideas, and giving the whole process the ring of truth. Many therapeutic case studies suffer from being told in the analyst’s voice, often to the exclusion of the patient’s personality, but in Winnicott’s work the child’s imagination itself is to the fore. The experience for the reader is correspondingly exciting as we discover with surprise each child’s next unpredictable contribution. As Winnicott tended to present cases outside the extremes of ill health, the reader is not made into a voyeur of other people’s tragic illnesses: rather than use their squiggles to show how ill the patients are, he used them to expand our idea of how normal the ‘madness’ of spontaneity is.

The publication of his Collected Works allows us to explore many of his squiggles and drawings for the first time, demonstrating a level of personal creativity that is not always evident in his theoretical writings. Winnicott was fostering a space for doing and letting happen, for a person to make contact with their own unfettered liveliness, for quotidian pursuits: squiggling, doodling, whistling, playing about, making a mess for its own sake, and then using it, or throwing it away.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in