Will executive pay pop up in Theresa May’s manifesto? An objective of her snap election is to secure a larger majority on the basis of a smaller burden of manifesto promises than she inherited from David Cameron. But in her only leadership campaign speech last July, her reference to ‘an irrational, unhealthy and growing gap between what those companies pay their workers and what they pay their bosses’ was one of the phrases that caught the most attention.

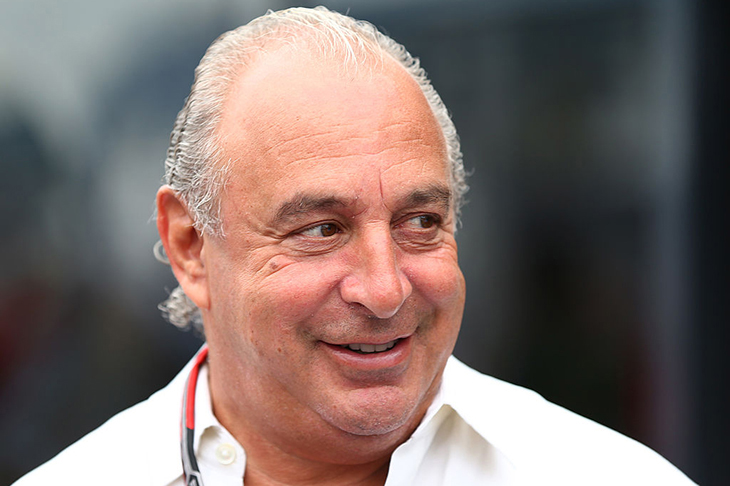

Back then, she was in favour of imposing annual binding shareholder votes on boardroom remuneration, as well as spotlighting the ratio between chief executives’ and average workers’ pay, and even forcing companies to accept workers’ representatives on boards. At last November’s CBI conference, however, she backed away from that last threat, resorting instead to what I described as ‘mood music’ designed to lure corporate support for her Brexit stance with talk of the lowest corporate tax rates in the G20 and more state cash for research and development. A green paper on corporate governance reform published in the same month made no new ripples, and was spun largely as a threat to bring listed company rules to bear on large private businesses — such as, of course, those owned by that season’s pantomime villain, Sir Philip Green.

Now that Sir Phil has coughed up for the BHS pension fund and sailed over the horizon, the level of tabloid and public hostility to fat cats has subsided. So perhaps there’s no political need for the Prime Minister to tie herself to manifesto promises that would cause corporate disgruntlement at a time when she needs UK plc to be performing at its competitive best — even if that means allowing the greedy bastards that run it to go on grabbing grotesque rewards.

Labour’s John McDonnell says he will cap the top-to-average pay ratio by law in companies that seek public procurement contracts; by backing away from anything of the sort, the Tories can burnish their credentials as free-market champions. And they may be hoping that there’s now sufficient momentum of demand from shareholders for boardroom pay transparency and restraint that the free market is about to do the job for them.

Some hope, I hear you mutter. Just this week we’ve had news that Sir Martin Sorrell, the chief executive of advertising group WPP who took home £48 million for 2016, will have his annual pay capped at £13 million from 2021 — when he will be 77. As a gesture towards unhappy investors, that looks like a two-finger salute. But as the founder and 30-year builder of the global empire that is WPP, Sorrell really is a special case, and there’s no doubt that in more conventional public companies the issue of excessive pay is gaining more traction.

A simple search of current news stories reveals shareholder discontent at Aggreko, AstraZeneca, Credit Suisse, the fund manager GAM, Pearson, Reckitt Benckiser, Rolls-Royce, Schroders, Shire and Unilever, to name but a few — while one contrasting headline, ‘93 per cent of Goldman Sachs shareholders approve executive pay plan’, reminds us where the last redoubt will be.

Theresa May has far bigger priorities, as do the vast majority of voters, and she needs the simplest mandate she can get. So I won’t be surprised if she says very little about corporate issues during this campaign. But I hope she repeats her promise of an annual binding shareholder vote on executive pay — as a strengthening of current rules, introduced by Vince Cable, which require a binding vote every three years and an ‘advisory’ vote (all too easily set aside by boards) in the intervening years.

Yes, that would be an intervention of the kind that free-market think-tankers abhor. But it would serve to strengthen the hand of shareholders, rather than imposing the government’s will as to how much anyone should be paid. And shareholders, as owners, ought to be free to decide — and free to overrule complacent, back-scratching board members — how the spoils of their company’s performance are divided.

A globalised trade

‘Fixing the roof while the sun shines’ is what chancellors of the Exchequer regularly claim to be doing, though they rarely turn out to have achieved it. Showing them the way this spring, I’m having my summerhouse re-thatched, by the same master thatcher, William Tegetmeier of Scarborough, who last did the same job for me 25 years ago. His gentle, methodical, pre-industrial craftsmanship is a delight to watch. He tells me that in earlier days he sourced all his reed from Norfolk, but now it comes from France (best), Austria, Hungary, Ukraine, Russia and China (cheapest). Who would have imagined that globalisation would touch even this bucolic trade? But at least the top layer of wheat straw will still come from somewhere near Huddersfield.

Getting the bullet

‘Do you still hate bankers?’ asked an old friend whom I hadn’t seen for years, having himself made a good career in overseas banking. Not at all, I said, and I never did. It’s been my mission to shame bad ones, but there are many I have liked and admired. Among those was Julian Wathen, a Barclays overseas veteran who has died aged 93, and whose story illuminates one key fact: at least today’s bankers don’t get shot at.

As manager of the Limassol branch in Cyprus in 1956, Wathen survived being shot through the neck by an Eoka gunman who, the Times reported, ‘walked into his office, fired, and then decamped without interference from anyone’. Wathen’s successor Joseph Brander was shot dead on the steps of the same branch two years later. Then there’s Justin Urquhart Stewart — still very much with us as a market commentator for Seven Investment Management — who as a Barclays cadet in Uganda in the 1970s spent months in hospital after being machine-gunned in his car at a roadblock. Today’s lot, merely cursed by customers and hounded by columnists, have it easy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in