Brett Dean’s new opera for Glyndebourne is a big-hearted romantic comedy, sunny and life-affirming. Only joking — this is contemporary opera, after all. It’s about the usual stuff: neurosis, violence and toxic sexuality. Those seem to be the emotions most naturally suited to the language of mainstream contemporary classical music, and Dean speaks that language as brilliantly as Richard Strauss handled the idiom of an earlier generation. Whatever else this operatic adaptation of Hamlet might be, it’s a polished piece of work.

That takes some doing: Shakespeare isn’t naturally suited to the opera house. It was Verdi’s librettist Boito who first realised that the best way to retain the essence of Shakespeare while still leaving room for a composer is to dismantle the play and rebuild it on operatic terms. Dean’s librettist Matthew Jocelyn has done precisely that, trimming and reassembling Shakespeare’s text to zip efficiently through all the bits you can remember of Hamlet’s multiple plotlines, and playing some ingenious little games along the way. ‘To be or not to be’ is hinted at by the Prince but finally delivered, piecemeal, by the Players. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (cast as a pair of preening countertenors) are merged with Osric, and are therefore present at the end to be slaughtered by Hamlet himself, and very satisfyingly too.

Dean has done the rest, with a score whose glinting textures, shattering climaxes and queasy, deliquescent microtonal slides generate a powerful sense of something rotten in the fabric of this opera’s world. As you’d expect from Dean, it’s wondrously refined. An unseen chorus (distinct from some powerful choral crowd scenes on stage) smudges the orchestration while electronics generate unexpected thuds and rumbles around the auditorium — all suitably unsettling. There’s wit too (Dean uses an accordion to droll effect in the Players’ scene). But like a miasma or a migraine, the tension never really lifts. The whole opera feels like an extended mad scene, quite apart from Ophelia’s set piece wig-out in Act Two — as stylised in its trilling, gargling, chest-beating vocal writing as anything by Donizetti, and deliveredby Barbara Hannigan with showstopping bravura.

That’s certainly the impression created by Hamlet himself. It’s a colossal role, performed by Allan Clayton with fearless mastery of what sounded like wrenching vocal demands. Fumbling, shuffling, twisting his fingers, under Neil Armfield’s direction it’s never at any point clear that this Hamlet is fully sane — which may of course be the only sane response to the world depicted here. Dean’s musical characterisation is deft. Polonius (Kim Begley) has a quiet, mumbling motif for low clarinets and flutes and Ophelia’s two-note sigh of ‘Never’ recurs to haunting effect.

But there’s a lot of story to get through, and outside of the set pieces — which included a magnificently macabre turn from John Tomlinson as the Gravedigger (he also, neatly, appears as the Player King and the Ghost) — it didn’t feel like there was quite enough space for all the characters to develop. It’s hard to judge on a first night, and I’d be interested to revisit Hamlet on its third or fourth production. But with a cast of this quality — Rod Gilfry as Claudius, Sarah Connolly dignified and distraught as Gertrude — there was no shortage of dramatic weight. Vladimir Jurowski conducted with icy intensity, and Ralph Myers’s elegant sets never got in the way.

Armfield gave us a properly gory dénouement, too, with plenty of sword-fighting and buckets of blood. That’s never guaranteed these days. At the climax of Tim Supple’s new staging of Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse, as Ulisse, thrillingly, strings his bow and butchers the suitors, the goddess Minerva sauntered on with a paint pot and casually dabbed a red splodge on each of them. That was it. Later, stagehands fumbled awkwardly with firelighters and audience members sniggered as Ulisse and Penelope shared their heart-rending recognition scene. For much of the final act the surtitles were illegible, at least from my seat.

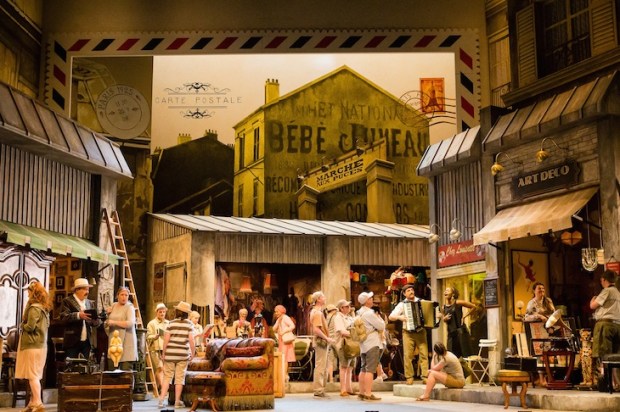

This is the debut production by The Grange Festival in the venue recently vacated (don’t ask) by the company still calling itself Grange Park Opera, and it’s clear that their artistic priorities are in the right place. Visually, though, this was all over the shop. Sure, enormous cat’s cradles and gods on bicycles are great as a means of mirroring the richness and fantasy of Monteverdi’s astonishing score. Not so great when they obscure crucial plot points. But I’ll give the new team at The Grange the benefit of the doubt because the performances were generally strong, with a lively band under Michael Chance, a sweet-toned, heroic Ulisse sung by Paul Nilon with a gleam in his eye, and above all, Anna Bonitatibus as Penelope: proud, passionate and able to maintain a regal dignity even while wearing something that looked less like a dress than a gazebo.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in