The ancient Greeks had a word for it —katabasis, descending into the depths, to the underworld itself, in search of answers. To cross the threshold between life and death, innocence and knowledge, the everyday and what lies beyond, is an act woven through art, resurfacing in each generation. For Orpheus, and for Monteverdi, the journey may be a literal one, but for Bartok’s Bluebeard, imagined in the age of Freud and Jung, hell is not found outside, or even in other people, but within the darkest recesses of our own selves.

When we speak of Orpheus it is of music, of birds and beasts beguiled, and men and women drawn into dance. But beginning with the tortoise shell and the gut strings that made up the very first lyre, this is music conjured from death, pain transfigured into beauty. If you look at paintings and sculpture — works by André Masson, Jacques Lipchitz, Ossip Zadkine — often the man and his instrument become one, fused into a single living lyre. Orpheus is split open, music vibrating from within his own belly. The act of musical creation is also an act of self-destruction, a sacrifice of life for art’s sake.

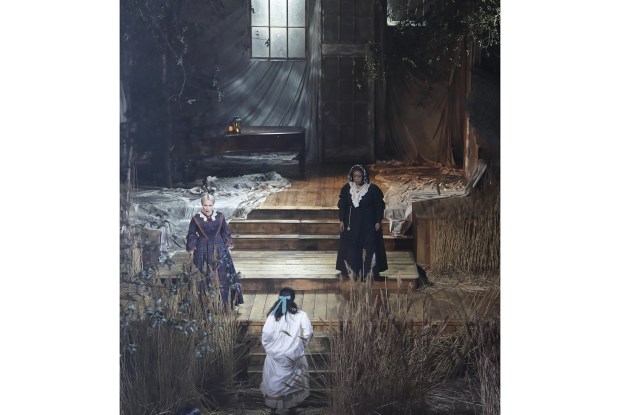

Monteverdi understood this. He gave us the blazing glory of L’Orfeo’s opening brass toccata, but also the bittersweet string ritornello that is the work’s musical touchstone, the searching, yearning agony of Orfeo’s plea ‘Possente spirto’. There’s dancing and joy and irrepressible energy to John Eliot Gardiner and Elsa Rooke’s urgent concert staging, but there’s also more darkness, more pain than you find in the opera house, where the work’s interior drama is too easily diluted by spectacle.

It’s interesting to see just how much Gardiner’s thinking has moved on since his performance of L’Orfeo at the 2015 BBC Proms — a warm-up, it now seems, for his current year-long international tour of the three Monteverdi operas. Even allowing for the particular space and crowd, that staging was a celebration, a drama where loss was cushioned by delight in music itself. But now there’s a sense that, even if Monteverdi cannot bear to give his hero an authentically bloody end at the hands of the maenads, Gardiner would like to.

With more roles than singers, casting in L’Orfeo is as much interpretation as practicality. Where previously Gardiner doubled the roles of La Musica and the Messenger, here he pairs La Musica with Euridice. That one singer (immaculate soprano Hana Blazikova, severely beautiful of tone) should serve as both muse and beloved to Krystian Adam’s Orfeo makes this quite a different story.

In the most delicate of gestures — a hand outstretched towards the harp, then reluctantly withdrawn — Rooke paints Orfeo’s conflict between life and art, distracted even on his wedding day by another love. Music is the medium of L’Orfeo, but it is also hero and heroine, something this semi-staging, with the orchestra onstage at its heart, makes wonderfully clear.

Running straight through with no interval, carried along by skilful choreography and the energy of the Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists, this Orfeo is a true ensemble affair. You may walk away remembering Gianluca Buratto’s inky Charon or the exquisite anguish of Adam’s Orfeo, but it’s just as likely to be the rhetorical swell and surge of the orchestra, breathing with the singers as they join them in telling a tale that never loses its urgency.

Originally composed for a competition, Bartok’s one-act opera Bluebeard’s Castle was rejected as not suitable for the stage. Though history has overturned that initial judgment, it’s another work whose drama is all in the music, that thrives in the imagination of the concert hall. With the Budapest Festival Orchestra’s conductor Ivan Fischer taking the role of the narrator himself, speaking the Prologue from the podium, the effect was of an incantation.

Wizard-like, Fischer summoned his story in all its queasy beauty — the insinuating, fragrant clarinet behind the garden of the Fourth Door, the bone-cracking xylophone of the First Door’s torture chamber, the scorching C major that is the Fifth Door’s boundless vista — his orchestra colouring each vision lovingly, a throbbing hit of colour against which Ildiko Komlosi’s Judith and Krisztian Cser’s Bluebeard were vividly silhouetted.

Veteran Komlosi may no longer sing the role as beautifully as she once did, but she lives it with such clarity that it scarcely matters. Despite all the orchestra’s warning, we hope along with her, believing absolutely in the passion between her and Cser’s seductive, plausible Bluebeard.

Where Charles Perrault ended with a murder, Bartok and librettist Bela Balazs end their tale in a symbol, a riddle. Like Orpheus before them, Judith and Bluebeard have descended into hell. Whether, having glimpsed its horrors, they, too, can emerge seems impossible. But it says much of this performance that, against all reason, you left still hoping.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in