The language of diplomacy often requires nuance and subtlety. Not infrequently, it needs to be opaque, to enable differing interpretations; consequential alternative conclusions and an accompanying diversity of courses of action.

This is seen at its finest in the response of the Hapsburg Foreign Minister Prince Metternich, when told that his great French rival, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, had died. Paying Talleyrand the ultimate diplomatic compliment, Metternich asked quizzically: ‘I wonder what he meant?’

No such opacity overwhelms Australian diplomacy since 1942, the pivotal year in our country’s foreign relations, according to Allan Gyngell in this convincing analysis.

Gyngell is an accomplished former diplomat and political adviser, having served governments on both sides of the aisle and having retired as Director-General of the Office of National Assessments in 2013. Gyngell understands the realities of policymaking, which he demonstrated exclusively in an earlier collaborative effort, Making Australian Foreign Policy, showing the benefit not only of foreign postings but of working as speechwriter to PM Paul Keating.

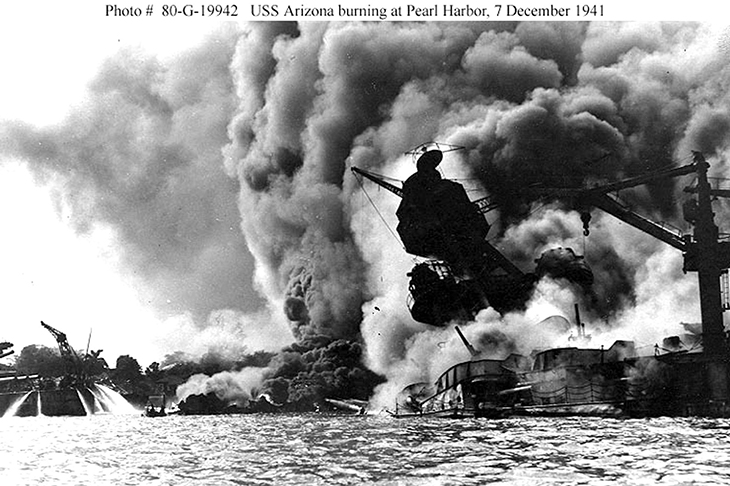

1942 was indeed a year of both confrontation and challenge for Australia.

The war reached Australian shores, with Japanese air raids on Darwin, Broome and elsewhere in the North and a submarine penetration of Sydney Harbour. With most of Australia’s armed forces in Europe and the Mediterranean, Australia faced the possibility of enemy invasion, especially after the fall of the British bastion at Singapore in February. PM Curtin recalled our troops, while realistically looking to the United States for Australian survival. The seeds of ANZUS, nourished by an effective war time alliance, were sown in the aftermath of Britain’s expulsion from East Asia.

Finally, Australia enacted the Statute of Westminster, passed by the British Parliament in 1931, which empowered the self-governing Dominions of the Empire, to pursue their own foreign policies.

Gyngell summarises:

The one indisputable marker of the nation’s sovereignty as a full member of the international community was the ratification of the Statute of Westminster in 1942 by John Curtin’s Labor Government, which had taken office just before the outbreak of the Pacific War. That was the point at which Australia was legally free from any residual formal constraints by London.

The post-war world meant dramatic shifts in the foreign landscape for Australia, with emerging nationalist movements in Southeast Asia, especially in Indonesia (Dutch East Indies); the challenge of militant and aggressive communism, as in Korea, and the general seismic movement towards decolonisation from India to Vietnam. The framework for post-war co-operative decision-making was to be the newly created UN. The Australian Foreign Minister charged with the direction of policy was the mercurial and irascible Doc Evatt.

Gyngell sums up:

Evatt was one of those people about whom almost everything that everyone said was true. He was ferociously intelligent, ambitious and hard-working, but also prickly, vain and self-centred. ‘What was the daemonic urge that drove him on?’ asked Paul Hasluck, who worked with him extensively… ‘Ambition is too simple a reply’.

Evatt was indeed flawed, but even Hasluck acknowledged the impact of the Doc’s work in the formation of the UN, where he served as founding President of the General Assembly. Australia established a reputation for vigorous international diplomacy, being able to speak for smaller powers on issues as diverse as economic, social and cultural rights.

But relations with the great powers posed very different dilemmas. The eclipse of the British Empire caused Australia to embrace the global power of the US, which had been growing in influence since 1915, when it had effectively become the war time banker to the Allies, Britain and France.

The commitment of the Chifley government to a punitive peace treaty with Japan, including trying Emperor Hirohito as a war criminal, gave way to a more conciliatory approach under the succeeding Menzies Government, which understood that the Americans wanted a more lenient agreement, given the pressures of the developing Cold War. It was the need for a peace treaty with Japan which offered Australia the opportunity to secure reassurance on our security. The earlier notion of a Pacific Pact, including Britain, was jettisoned, as London displayed little interest. Gyngell pays due regard to the work of Foreign Minister Percy Spender, who laboured mightily to craft a defence agreement with the US, in the face of the indifference of his PM, Robert Menzies, who saw more importance in Europe than Asia.

In February 1951 Dulles, as Truman’s envoy, arrived in Australia to pin down Australian support for the peace treaty with Japan. At a meeting in Canberra with Spender and his New Zealand counterpart, Frederick Doidge, the outline of the ANZUS Pact – which Spender had already asked his department to draft – was worked out.

Spender signed the treaty in San Francisco on 1 September 1951, just before the Japanese peace conference opened… For the first time in its history, Australia had entered into a foreign defence engagement to which the United Kingdom was not a party.

The ANZUS treaty, despite the breaking of the trilateralism of the pact by the Lange Labour government of New Zealand in the 1980’s, has endured ever since as the bedrock of Australian foreign relations and national security policy. It continues to enjoy consistent bipartisan endorsement and broad popular support, despite the divisiveness of issues such as the Vietnam War.

One element of ANZUS that fits neatly into the book’s thesis of fears of abandonment was the oft-voiced complaint of successive Australian ambassadors to Washington, who lamented the endless entreaties of visiting Australian ministers, seeking declarations to define ANZUS beyond doubt and the prerogatives of the American Senate.

Gyngell is a thoughtful writer, who weighs his subjects carefully and argues conclusions with both clarity and definition. His book is divided logically and enables a convincing perspective on our post-war diplomacy, through sound decision-making as on Indonesian independence; through agonising deliberations as in the enduring White Australia policy to Australian successes such as APEC. This is a fine book, well researched and persuasively written. It should be mandatory reading for all aspiring Australian diplomats.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in