Ernst Bertram’s study Nietzsche: Versuch einer Mythologie was published in 1918, but its first English translation, under the subtitle Attempt at a Mythology, did not appear until 2009. This much-praised work finally became available to Anglophone readers, and maybe, just maybe, its influence will help to mitigate the errors of scholars and readers who too facilely paint this great philosopher as a fascist soul-mate of Mussolini and Hitler. In the grip of such IYI (Nassim Taleb’s acronym meaning ‘Intellectual Yet Idiot’) thinking, the student council of University College London recently banned a proposed Nietzsche club on the grounds that it would be ‘directly threatening to the safety of the UCL student body’.

Welcome to the febrile world of victim drama states and snowflakes, sanctioned and potentiated by social media, of which the typical US or UK campus is the most monstrous example. Undergraduate activists have long been renowned for their inanity, but so what? – they did no harm, and they would grow out of it, as experience became their teacher. Now they are dictating policy to supine university leaders. and their level of idiocy has spread far beyond the campus, so that Clementine Ford, for example, whom I daresay would not have been tolerated in a major newspaper as recently as a decade ago, has become mainstream.

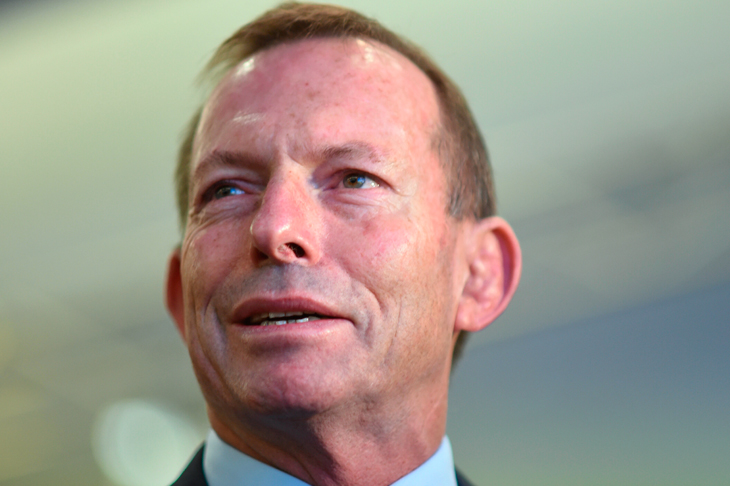

This is the anti-Trump constituency, as tragicomically unable to develop a holistic view of a complex human being as they were, mutatis mutandis, in the case of Tony Abbott. Their reaction to Trump has been of the same quality as their monocular attitude to Nietzsche. Bertram’s study in contrast comprises nineteen chapters, with titles such as ‘Ancestry,’ ‘Judas,’ ‘Weimar,’ Claude Lorrain,’ ‘Prophecy,’ ‘Eleusis,’ and so on. Such a multi-faceted approach can provide a coherent appreciation of a complex subject in its wholeness.

The chapter that is of most interest to us here concerns a man for whom Nietzsche had greater admiration than for any other historical figure. Goethe met this man in person, and Bertram quotes his record of the meeting:

‘He had it, and one saw by looking at him that he did; that was all… He had to an eminent degree a thoroughly demonic nature, so that hardly anyone else can be compared to him. The Greeks counted demonic natures of that sort among the demigods… His life was the procession of a demigod… One may very aptly say of him that he found himself in a state of perpetual inspiration… He was one of the most productive men who have ever lived.’

Nietzsche said of this man – let us call him X – in various works: ‘The major event of the last millennium is the appearance of X’; ‘X, the first and most advanced person of modern times’; ‘the history of X’s influence is virtually the history of the higher happiness that this entire century achieved in its most worthy people and moments’; ‘we owe almost the whole of the higher hopes of this century to X’; ‘The ancient ideal stepped bodily and with unparalleled splendor before the eyes and conscience of humanity.’ In Twilight of the Idols Nietzsche wrote, ‘X was an example of the return to nature, as I understand it’, and Bertram glosses, ‘a return to ancient nature, not Rousseau’s.’

In 1807, Goethe wrote that extraordinary people such as X step out of morality, and that in the end they act like physical elemental causes, like fire and water. Nietzsche put his attitude to X in a nutshell in The Gay Science:

‘X, who saw in modern ideas and particularly in civilisation something like a personal enemy, and by this hostility proved himself to be one of the greatest among those who have continued the Renaissance: he brought an entire element of the essence of antiquity, perhaps the most decisive one, the element of granite, to the surface again.’

You’ve guessed it. Yes, X is Napoleon. But he could so easily be, with some modifications, Donald Trump. I interpret Nietzsche’s use of the term ‘civilisation’ as germane to Spengler’s in The Decline of the West, as the petrifying end stage of a great culture. I suggest that we might justifiably substitute, in the modern context, ‘political correctness’ for ‘civilisation’.

And here may be a clue as to why Trump so enrages, as did Abbott, the ‘civilised’ crowds (their latent viciousness is not inconsistent with this) of social and other media. There is an elemental quality to both of those men, which causes their critics too facilely to portray them at best as country bumpkins, at worst as regressive sociopaths.

Napoleon’s hostility toward civilisation was reciprocated, as it is with all such men. Nietzsche wrote, in an aside to The Gay Science, that, ‘Basically all civilisations have the same deep fear of the “great man” that the Chinese alone have admitted to themselves in their saying: “The great man is a public misfortune.” Basically all institutions are organized so that he arises as infrequently and under circumstances that are unfavourable as possible.’ This is uncannily apposite to the Trump ascendancy.

There is also much of the ‘return to nature’ in the Abbott personality. With his surf life saving and fire service volunteering, his obviously genuine concern for indigenous communities in remote Australia, and his renowned backwardness in economics, he is clearly not a man who could have found his career satisfaction in, say, PwC (or should we just say ‘PC’?). Budgie smuggler jokes notwithstanding, Fairfax was mostly balanced and generous toward Abbott when his encounter with his supposedly illegitimate son was all over the media. I would argue that the onset of the madness coincided with the rocketing ascendancy of social media, which provided a fertile soil for it. Unfavourable circumstances indeed.

The sub-undergraduate media might well seize upon the Trump-Nietzsche association with glee. But, digging an atom down to where they would already be out of their depth, the Trump-Napoleon connection will take more explaining, and could be an insuperable barrier. Come the day.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in