‘Peter Grimes!’ Ranked high above us in the Usher Hall — a mob smelling blood, hot for the kill — the chorus let forth those three primal cries, and we were all lost. The modesty-curtain of civilisation was torn away, and our basest human urges — hate, revenge, suspicion of difference, delight at weakness — were exposed. Looking up at those faces, shielded by no proscenium, separated by no stage lighting, I don’t know when I have ever felt more horrified, more shaken by a performance.

‘A staged concert,’ writes conductor Ivan Fischer, ‘looks for complete harmony and coordination between music and theatre… for organic unity in which vocal and acting skills merge completely.’ He’s not wrong. But nor is he alone in recognising the infinite theatrical possibility of opera in concert. Sadly, his own Edinburgh International Festival Don Giovanni (designed, he laboriously explained, as a ‘staged concert’ and definitely not a ‘semi-staging’, with all the half-heartedness that implies) was a limp affair compared to the ferocity of this weaponised Grimes.

No amount of semantic play or rhetorical sleight-of-hand could conceal the fact that this Giovanni — conducted and directed by Fischer himself — was over-conceptualised and under-realised. ‘The singers will play themselves, wearing their own evening dress,’ he claimed. But that of course was nonsense. What we got was a black-box production in which an approximately costumed cast improvised a basic staging. Were it not for the densely coloured orchestral playing and the unusual chorus we might have been watching a show at the Edinburgh Fringe and not the International Festival.

Made up of students from Budapest’s University of Theatre and Film Arts, the chorus, whitewashed and loin-clothed like a whole gallery of Pygmalion’s sculptures come to life, were the living furniture and fabric of a world viewed through the Don’s lustful eyes. Transforming themselves by turns into tables, chairs, rooms and, most effectively, clawing demons in the final scene (Fischer’s hell is quite literally other people), they were also a striking reminder of the distance between human reality and marble archetype, of the dangers of essentialising and fossilising an all-too-human figure like Giovanni.

But this was where the interest began and ended. Christopher Maltman’s charismatic, generously projected Don aside, the cast of smallish voices failed to do much more than go through the motions. After an opening Sinfonia that crackled with gritty life, Fischer’s speeds hardened up like the plaster on his living statues, settling into uncharacteristically matronly tempi — a soundtrack for slippers-and-cocoa, not for seducing.

But if the chorus were the decorative focus of Fischer’s Giovanni, they were the dramatic engine of the Bergen Philharmonic’s concert performance of Peter Grimes. Under conductor Edward Gardner, this Norwegian ensemble has taken this music to its heart and into its blood, catching both the violence and — even more bruising — the tenderness of Britten’s tragedy.

The steeply raked choir stalls of the Usher Hall are a gift to a piece in which the villain is an entire community. Stuart Skelton’s man-child Grimes may be a giant of a figure on his own terms, but was dwarfed here by a towering human mass made up of the Edvard Grieg Kor, Choir of Collegium Musicum and students from the Royal Northern College of Music — the living embodiment of the sea in their muted blues, greys and greens, and just as powerfully destructive.

The partnership of Gardner and Skelton in this piece is a familiar one to UK audiences, who have already seen it several times both at ENO and the Proms. So to say that this was a performance apart — an assault of an enactment, piercing the skin in the opening court scene, then probing only deeper through the evening — is not the shock of the new. Skelton’s is surely the greatest living Grimes. Gone is the visionary purity, the pianissimo innocence of his early performances, but in its place we get a whole lot more power and rage, a Grimes carved out rather than painted on. This is a man absolutely on the edge, both dramatically and vocally — more sinning than sinned-against, and all the more powerful for that new and horrible agency.

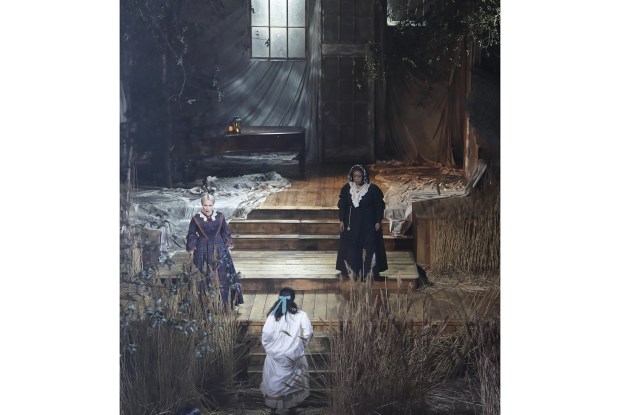

It would have been easy for this to have turned into a two-hander for Skelton and Gardner, but in Vera Rostin Wexelsen’s telling staging the entire cast emerged in richly human detail. If there’s a warmer, more radiantly sung Ellen Orford than Erin Wall’s, then I’ve yet to hear it. Blazing out alongside Christopher Purves’s Balstrode (no saint he, but a red-blooded man, excited by Auntie’s nieces), she alone remains untainted.

The Borough’s other residents — James Gilchrist’s preening, fluting vicar, Robert Murray’s highly strung Boles, Susan Bickley’s no-nonsense Auntie and Catherine Wyn-Rogers’s self-righteous busybody of a Mrs Sedley — were the finest ensemble imaginable. What Grimes on the Beach achieved through site-specific resonance and context, this Peter Grimes managed through the music alone — an extraordinary feat, and one that still stings sour behind the eyes several days on.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in