If there were a prize awarded to the book with the best opening line, A. N. Wilson would be clearing a space on his mantelpiece. ‘Darwin was wrong’, he announces at the start of this hugely enjoyable revisionist biography, which will be read in certain scientific circles to the background noise of teeth being ground and knives being sharpened. A brilliant Victorian naturalist, certainly, and still an inescapable cultural presence — think of Darwin staring out benignly from the £10 note — but according to Wilson, also a passive aggressive racist whose evolutionary theories no longer stand up to scrutiny. If that doesn’t put the felis catus among the columbidae it’s hard to know what will.

These days probably fewer people encounter Darwin through his writings than they do through his statue in the entrance hall of Kensington’s Natural History Museum. Thickly bearded, with one leg carelessly crossed over the other, he looks both grandly imposing and surprisingly down-to-earth, like an Old Testament prophet waiting for the bus. In many ways that is also how his theory of evolution has come to be thought of in the wider culture. Though built upon minute observations of the natural world — nobody was better than Darwin at spotting tiny deviations in the curve of a bird’s beak, or in the delicate folds of a mollusc’s shell — the theory quickly outstripped his scientific data, and instead became a grand narrative seemingly capable of explaining the entire history of life on earth.

Seen through Darwin’s eyes, suddenly the world looked very different. Birdsong was no longer an innocent celebration, but a set of warnings and sexual invitations; flowers were no longer cheerful splashes of colour in the landscape, but hostile organisms engaged in a turf war. Wherever you looked, different life forms were part of an endless struggle for survival. The only problem, Wilson points out, is that this was a myth.

The fossil record and recent DNA discoveries indicate that evolution does not proceed through infinitely small gradations; rather nature makes sudden leaps. Nor does progress depend only upon selfishness and struggle. Collaboration is just as important as competition: ‘Ants don’t build anthills by fighting one another; nor bees hives.’ And it turns out that the same is true of evolutionary theory itself, for although Darwin’s was the name that became attached to the idea of species evolving through their adaptation to environment, this was the result of co-operative scientific efforts that could be traced back to his grandfather Erasmus Darwin and beyond.

This is a story that has often been told, including the carefully stage-managed meeting of the Linnean Society in 1858 when Darwin’s theory was announced alongside that of Alfred Russel Wallace, who had independently come up with a very similar idea and effectively bounced Darwin into claiming it for himself. What Wilson brings to this sequence is a clear-eyed understanding of the ruthless ambition behind Darwin’s gentlemanly pose. For whether or not other living creatures sought personal advantage, Darwin certainly did everything he could to ensure that his theory would elbow its way to the top: a theory that allowed the growing Victorian middle class to convince themselves that their success in life was simply part of the natural order, as inevitable as a dog’s urge to rip apart a nest of rats.

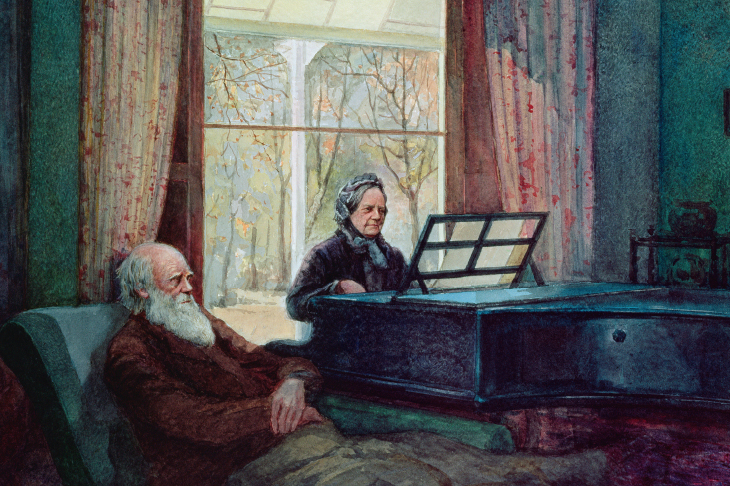

The picture of Darwin that emerges from this biography is a mixed one. On the one hand, he spent most of his adult life as a martyr to symptoms that ranged from eczema to flatulence, and he was patiently looked after by his wife Emma, or ‘Mammy’ as he liked to call her, as if she hadn’t so much married him as adopted him. On the other hand, he assumed that men like him were naturally superior, not only because of their wealth (an immensely rich father and marriage into the Wedgwood family meant that Darwin never had to earn a living) but also because of their race, expressing his relief that ‘civilised nations are everywhere supplanting barbarous nations’. He was an unsentimental believer in Malthus’s theory of populations regulating themselves through famine and disease, but was devastated when his ten-year old daughter Annie died of tuberculosis. And as his religious faith slowly slipped away, so he developed a theory that would later become a substitute religion for many.

Wilson unpicks these contradictions with a scientist’s forensic skill and a novelist’s imaginative touch, whether he is describing the ‘routine of comforting dullness’ that characterised Darwin’s married life, or the ‘patient, slow decade’ of the 1850s in which his notebook jottings finally took shape. He has a pouncing eye for the eccentricities not only of Darwin himself, whose study at his family home in Kent included a curtained- off chamber pot for gastric emergencies, but also characters like his daughter Etty. Her long-suffering servants had to place a silk handkerchief over her left foot to prevent it from getting cold, and she protected herself against germs by wearing ‘a sort of gas mask of her own invention, a wire kitchen-strainer stuffed with antiseptic cotton-wool and tied on like a snout with elastic round her ears’.

Wilson also does a superb job of sketching out how Darwin’s ‘consolation myth’ slowly took on an unstoppable cultural momentum. To adopt W.H. Auden’s account of psychoanalysis in his poem ‘In Memory of Sigmund Freud’, by the time of his death in 1882 Darwin had created ‘a whole climate of opinion / Under whom we conduct our different lives’.

It was an atmosphere that quickly soured, as loose notions of ‘the survival of the fittest’ (Herbert Spencer’s phrase) were used to justify eugenics and worse. Just as ‘The fly is snapped up by a dragon-fly, which is itself swallowed by a bird,’ one writer observed, so ‘Necessity will force us to be always at the head of progress’. That could be any of Darwin’s contemporaries talking. In fact it is Hitler calmly explaining in his Table Talk why ‘All life is paid for in blood’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in