Last week, the Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2017 was introduced before the Legislative Council of New South Wales.

In one sense I am not surprised. The current politico-moral climate is one in which it is increasingly onerous – and in some circles, even inappropriate – to assign value, meaning, and worth to human existence.

There is a tragic irony in the knowledge that a parliament will recognise suicide prevention day and within the same month debate a bill to introduce euthanasia. We invest a significant amount of resources in talking people out of contemplating suicide only to consider reversing this when they may be at their most vulnerable and in need of our love and support.

We have become far too comfortable with speaking of human life critically – as noxious to the environment, or taxing upon the economy, or straining upon our relationships, or burdensome to the wider population. Human life is perhaps more commonly perceived as a negative contribution to the created world rather than as a basic good and brimming with latent potential. The rhetoric of popular culture represents an enormous crisis in Western humanist thought as we are confronted by the dearth of the belief in the sacrosanctity of human life.

Irrespective of what might be deemed a “worthwhile quality of life,” at the core of Western humanist thought is the Judaeo-Christian tradition that all persons are in possession of an intrinsic, inalienable worth.

I am thankful for my parliamentary colleague, Walt Secord, who recently wrote that “parliamentarians cannot codify legislation on how to end a human life.” In fact, I hold the position that governments cannot legislate or licence the killing of innocent people without risking the loss of the character of their authority.

In fact since the abolition of capital punishment in NSW, if it is passed, this will be the only piece of legislation by our parliament to allow for the State-sanctioned killing of people. Worse still under the proposed Bill, there is no duty to inform the decision makers relatives of the decision which has been taken with the consequence that the first family members may be told of the decision is after their father, mother, brother or sister is dead.

I certainly sympathise with the stories of those who have suffered tremendously at the waning of life and would want to see them receive the best possible end of life care. It would be an exceptional case indeed to find anyone whose hearts are not stirred by such unhappy circumstances.

Those with whom I have spoken to who advocate for assisted dying have come from positions of compassion, sincerity, and kindness. They are driven by love, genuine and pure.

However, neither side of the debate can claim a monopoly on compassion as there are clearly compassionate arguments to be made for and against. But it is seldom wise to make decisions purely based on emotion; we must also look at the potential consequences and practical application of that decision.

Compassion by itself cannot, and will never be, an ultimate solution. Assisted dying can seem like the cutting of a knot to an otherwise Gordian moral conundrum, however, it is fundamentally a false promise to suggest that we are truly loving people when what we are wishing for is their untimely and premature demise.

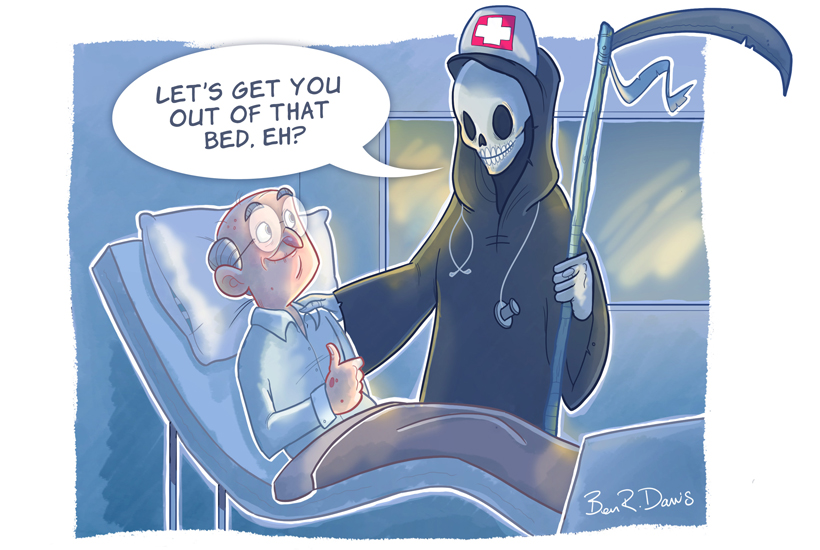

When does it become the role of medical practitioners to facilitate the ending of a life rather than trying to save it? There appears to be an uncomfortably close relationship with a patient’s ‘right to die’ and their unspoken ‘duty to die,’ especially for those who are very ill, infirm, or those whose lives are unfairly caricatured as a ‘disvalue’ to society.

When a human life begins, we hold to an unshakeable conviction that that life should go well, that the investments and aspirations attached to that life represent hopes and dreams to be realised rather than frustrated. Should such a position change for a person whether at the dawn or the twilights of their lives? In years gone by, Rudyard Kipling penned the words, “fill the unforgiving minute with sixty seconds’ worth of distance run”. We as a nation possess the capacity to provide solutions for the realisation of such ideals even for those suffering with terminal illnesses.

I would posit one question before closing: how ought we to interpret the plea of patients for assisted dying? I am not convinced that the desire for escape from this present life is a plea for “death with dignity” inasmuch as it might be better interpreted as a plea for better care, support, comfort, and love in a world so vacuous of such things. In legalising assisted dying, the death of love – of true love – looks to shortly thereafter follow. Is it more loving to offer a hand to prescribe a lethal dose to those who have reached their final moments, or to offer a hand to guide them in what I can imagine for many to be a season of great loneliness and anxiety? I hope, trust, and pray that our great nation of Australia will come to the right conclusion.

Damien Tudehope is the Liberal Member for Epping in the New South Wales state parliament.

Illustration: Ben R Davis.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in