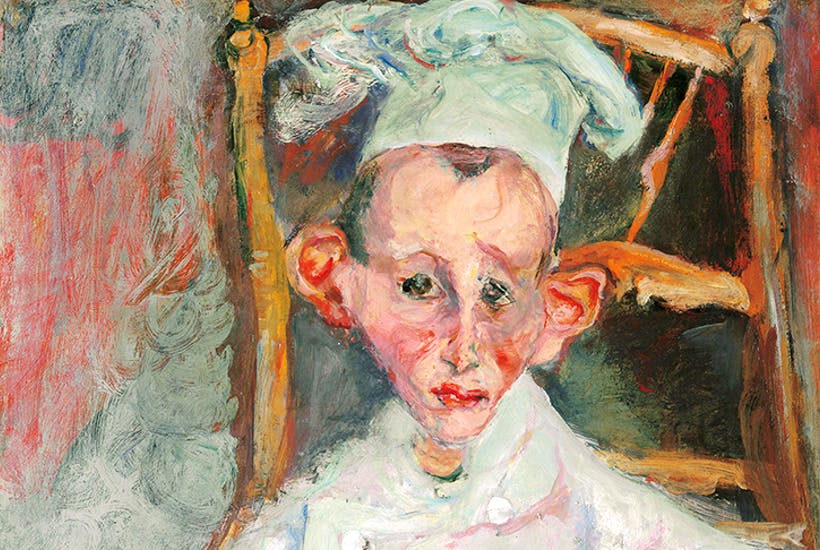

The first pastry cook Chaïm Soutine painted came out like a collapsed soufflé. The sitter for ‘The Pastry Cook’ (c.1919) was Rémy Zocchetto, a 17-year-old apprentice at the Garetta Hotel in Céret in southern France. He is deflated, lopsided, slouch-shouldered, in a chef’s jacket several sizes too big for him. His hat is askew, his body a scramble of egg-white paint.

Soutine painted at least six cooks in their kitchen livery. In their chef’s whites they look like meringues that have not set (‘Pastry Cook of Cagnes’, 1922), îles flottantes that do not float (‘Cook of Cagnes’, c.1924), and, in the case of the ‘Little Pastry Cook’ (c.1921) from the Portland Art Museum, Oregon, a wiggling line of piped crème pâtissière.

Rémy, the first of Soutine’s ‘petits pâtissiers’, sat six times for the artist. At the end of the last session, Soutine offered the boy a painting instead of the ten sous a sitting he had promised. ‘I was a fool to refuse,’ said Rémy years later. ‘I can understand that now, but his painting seemed to me awfully bad.’

To Rémy, perhaps, but not to the American collector Albert C. Barnes, who, seeing Remy’s portrait in the Paris gallery of Soutine’s dealer Léopold Zborowski in 1922, exclaimed: ‘But it’s a peach!’ Barnes sent a car to fetch the 29-year-old Soutine, who couldn’t afford the price of a coffee in a café, from a bench in Montparnasse. Soutine was delivered, unwashed, to the gallery. Barnes had Soutine take a bath, ordered him clothes from an English tailor, installed him in a smart studio, and proceeded to buy a large number — some say 52, some 54, some as many as a hundred — of his paintings. Thanks to that first ‘peach’ of a pastry chef, Soutine never sat on a bench for want of a sous again.

Five of the pastry cooks appear in Soutine’s Portraits: Cooks, Waiters and Bellboys at the Courtauld Gallery. We know Soutine for his landscapes at Cagnes, worlds tilted on their axes; his still lives of wizened chickens and scraggy pheasants; his hulks of bloodied beef. This fascinating exhibition brings together for the first time Soutine’s portraits of the pâtissiers, chefs, butchers, waiters, grooms, valets, bellhops and chambermaids of France’s grand hotels and restaurants in the boom years between the wars. Here is the below-stairs, service-corridors world of George Orwell’s Hôtel X in Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), of snob waiters, sodden plongeurs and scheming soubrettes. Orwell tells the story of the chambermaid who stole a diamond ring from the room of an American lady. While detectives ransacked the hotel and frisked the staff, the chambermaid had the ring baked into a roll by her lover in the kitchen. There it stayed until the search was over. ‘Oh, yes,’ you think, looking at Soutine’s ‘La Soubrette’ (c.1933), with her sly smile and her white collar and apron not as neat as they should be. ‘She looks just the type.’

Soutine, even when elevated to suits and studios by Barnes, was in sympathy with the servants of the great hotels. Like him, many of them were immigrants (‘There is hardly such a thing as a French waiter in Paris,’ wrote Orwell) in search of a better life — the Parisian dream. Soutine’s ‘Page Boy at Maxim’s’ (c.1927) approaches us with hand outstretched, keen for a tip.

‘Never be sorry for a waiter,’ wrote Orwell. ‘He is not thinking as he looks at you, “What an overfed lout”; he is thinking, “One day, when I have saved enough money, I shall be able to imitate that man.”’ Soutine’s ‘Head Waiter’ (c.1927) stands, in bow tie and waistcoat, with his hands on his hips in the best tradition of the ‘swagger portraits’ commissioned by kings, knights and noblemen. He might be Hans Holbein’s Henry VIII off to dissolve the monasteries, not the maître d’hôtel about to uncork a Burgundy.

Chaïm Sutin (1893–1943) was born in poverty in Smilovitchi, a shtetl in Lithuania, part of the Pale of Settlement — the provinces in czarist Russia to which Jewish families were confined by imperial decree. ‘Chaïm’ is ‘life’ in Hebrew; the ‘Sutin’ he Gallicised on arrival in Paris in 1913. Soutine was the tenth of 11 children of a Jewish tailor. The young Chaïm wanted to paint — the Talmud had a thing or two to say about that — and stole utensils from his mother’s kitchen to buy a coloured pencil. He was punished with two days in the cellar. He asked the rabbi to sit for a portrait and was thrashed for his pains.

Nevertheless, he found a place at a small art academy in Vilna that accepted Jews, and later enrolled at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He shared a room with Amedeo Modigliani at La Ruche — ‘The Beehive’ — an artist’s colony in Montparnasse. They took turns in a single bed or on the floor. The bugs bit wherever they slept.

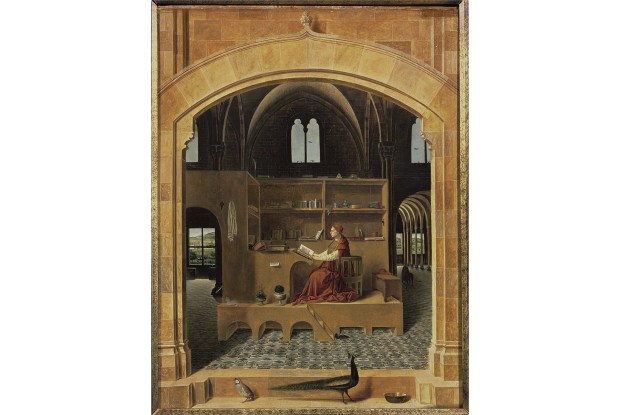

At the Louvre, Soutine discovered Jean Fouquet, El Greco, Goya, Courbet and Rembrandt. He invests his valets and room-service lackeys, slumped on chairs between shifts, with the authority of the throned popes of Titian and Velázquez.

One of the questions the exhibition poses is: when did Soutine paint these servants of the hotels? Not during kitchen service hours, when, Orwell tells us, the whole staff ‘raged and cursed like demons… there was scarcely a verb in the hotel except foutre.’ Not on their days off. Staff never knew such a thing. They worked 15 hours a day, seven days a week. In slack daytime hours, then? But Soutine hated to rush. ‘To do a portrait,’ he said, ‘it’s necessary to take one’s time, but the model tires quickly and assumes a stupid expression. Then it’s necessary to hurry up, and that irritates me. I become unnerved, I grind my teeth, and sometimes it gets to a point where I scream. I slash the canvas, and everything goes to hell and I fall down on the floor.’

Soutine was not a happy man. He hated to be reminded of childhood privations, but suffered guilt and remorse for not sending money home. He railed against the luxury that success with Barnes had brought him. ‘Can you imagine?’ he complained of one hotel. ‘Hot water, it made me feel uneasy; and also, I cannot paint where there are rugs.’

Nor could he eat in fine restaurants. As a boy he had gone hungry. As a man, a new bourgeois with money to spend, he ate plain fare and nursed stomach pains. He painted skate, trout and artichokes with the longing of the artist who looks but cannot eat. In 1943, while hiding from the Gestapo, he died during an operation on his stomach ulcers. Among the few mourners brave enough to attend his funeral was Picasso.

There is great pathos in his portraits of chefs and pastry cooks. He devoted himself to painting masters of the pâtissier’s art, turning kitchen-weary men into kings and popes — and never once a profiterole for his reward.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in