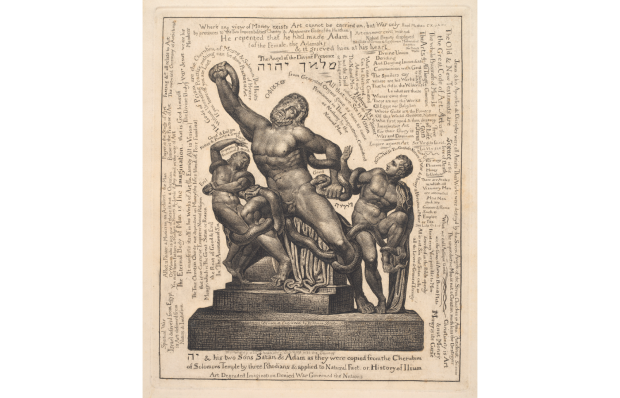

In the 1880s the young Max Klinger made a series of etchings detailing the surreal adventures of a woman’s glove picked up by a stranger at an ice rink. At a certain point the glove washes up, nightmarishly large, beside a sleeping man’s bed on to which a shipwrecked sailor is desperately hauling himself. Storm-tossed billows merge with rumpled pillows in an image simply titled ‘Angste’.

Klinger’s nightmare vision came back to haunt me at the exhibition Tracey Emin, ‘My Bed’/JMW Turner. Yes, you read that right. Since its loan to the Tate in 2015, Emin’s most famous oeuvre has been partnered in exhibitions with the work of Francis Bacon at Tate Britain and William Blake at Tate Liverpool. Now it’s the turn of JMW Turner at Turner Contemporary Margate — and, astonishingly, the partnership works.

This is largely down to Emin’s intervention in the choice of paintings. Rejecting the gallery’s own selection, she has dredged from the depths of the Turner Bequest two of the artist’s most expressionist seascapes: ‘Rough Sea’ (c.1840–45), a churning mass of bilious, white-flecked water, and ‘Stormy Sea with Blazing Wreck’ (c.1835–40), a canvas so black it could have been painted with pitch. Add a third painting, ‘Seascape’ (c.1835–40), in which a weak sun breaks through cloud, and the sequence charts the progress of Emin’s dark night of the soul from pit of despair to breakthrough moment, when ‘it stopped being horrific and started being beautiful’.

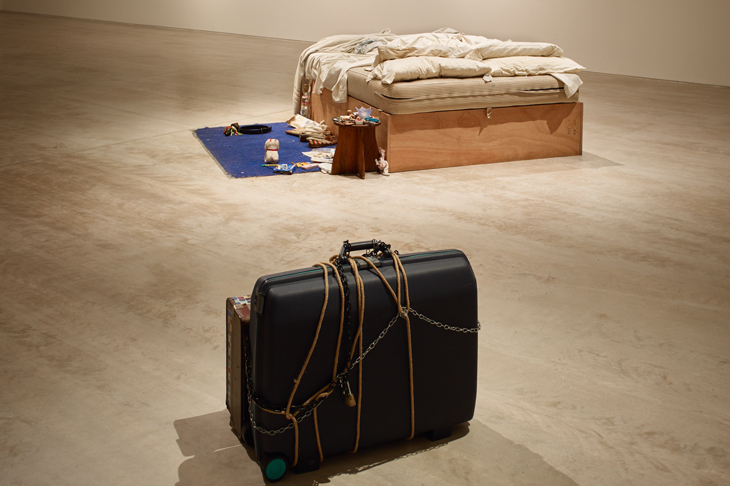

In previous passing encounters with ‘My Bed’ (1998), I’ve found myself more drawn to the two suitcases standing off to the side, lashed together with ropes and chains and tugging at the heartstrings with their talk of departure. This time, as a conscientious critic, I had a proper look. Prurient media attention has always focused on the feminine-hygiene items and bottles of booze, but the clutter includes other stuff of forensic interest. Here is a brief inventory (not exhaustive):

On the floor, a Duracell battery pack, empty; a carton of Marlboro Lights, empty; a soft toy dog; a rubber toothbrush; a tampon applicator; a tube of KY Jelly; a belt; three vodka bottles of different sizes, empty (two Absolut, one Stolichnaya); a bottle of Orangina, unopened, in which all the orange has drifted south; a pair of filthy fur-lined tartan slippers; a heap of tear-soaked tissues. On the bedside table, two blister packs of Anadin, empty; two condom sachets, full; a pile of loose change; a pack of Rizla; a champagne cork (where there’s Stolly there’s Bolly); an overflowing ashtray, topped with an ancient apple core; a ghostly Polaroid of the artist’s face, reminding us that this confessional self-portrait predates the selfie. On the shipwrecked bed, in place of Klinger’s monstrous glove, a pair of storm-tossed blue lacy pants and nylon tights, their tan faded with age to a gangrenous green.

In a filmed interview playing in the passage, Emin admits to having outgrown her bed — the belt that used to clinch her waist, she confesses with disarming candour, now meets around her thigh. The installation has become a ghost of what at the time felt like a matter of life and death: ‘I spent four days in the bed and when I got out I realised that it had probably saved my life… and at that moment I just saw it in a white space.’ As she points out, it’s equally unusual for Turner’s paintings to be shown in a white space, and it changes our perception. The oils lose some of their richness and mystery, but the 11 watercolour studies of coastal effects of light also on display gain in clarity and impact.

In Turner’s day, artists conjured light from paint; nowadays they can make it from electricity. Ann Veronica Janssens explores effects of light with technical means as slender in their way as Turner’s colour beginnings. Born in Folkestone in 1956, she is known for her mist rooms and fog pavilions, but there’s no fog in her exhibition at White Cube, Bermondsey, though there are mirrors and magic tricks. What are you looking at? It depends where you’re coming from. In ‘Sweet Blue’ (2010–17), a reflective glass cube containing paraffin oil poses a different 3-D puzzle from every angle; in ‘Magic Mirrors (Blue and Pink #2)’ (2013–17), the reflected overhead strip lights shift from green to pink to blue to yellow as you pass. A plume of white glitter thrown across the floor becomes a spume of sea foam; viewed against the flash of yellow and pink thrown by a dichroic-filtered light on to the wall behind, it could be a Turner sunset.

Janssens’s exhibition is an angst-free zone. Visit it after a rough night and you’ll emerge feeling cleansed; visit ‘My Bed’ after a week in a spa and you’ll come out feeling rough. Emin churns the emotions; Janssens clears the vision. Turner somehow manages to do both.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in