Leonard Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti begins not with a prelude, but a jingle. In Matthew Eberhardt’s production a trio of session singers clusters around a studio microphone. A clarinet throws out a slinky riff, the ‘On Air’ light blinks on, and they’re off: a swinging hymn to postwar suburbia, in Andrews Sisters close-harmony. Then we see a scene familiar from a hundred sitcoms and movies: all-American domesticity, 1950s-style. Clean-cut Sam is in his business suit, his prettily dressed wife Dinah fixes breakfast, and Junior scampers about in a cowboy costume. Bernstein establishes his world instantly, and Eberhardt sets it up with a deft touch. This is basically Mad Men — The Opera.

So you know the deal. It’s the hollowness of the American Dream, and sure enough, Sam and Dinah are bickering from the off. What unfolds as they drift through their day — him lording it at office and gym, her bunking off to a trashy matinee at the movies, neither of them bothering to show up for Junior’s school play — is a startlingly cool dissection of a marriage on a downswing. Bernstein’s score is fascinating. The harmonic primary colours come straight from Aaron Copland, but there’s a muscularity that looks ahead to Bernstein’s music for On the Waterfront, as well as big syrupy slugs of the faux-naïf uplift that mars Bernstein’s later stage works — though by having the couple turn and face a glittering Hollywood ending that they’ve done nothing to earn, Eberhardt manages to give the final peroration a necessary dash of bitters.

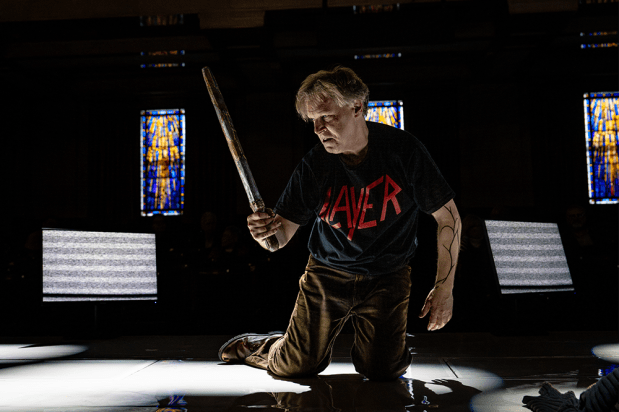

In fact, if this staging has a fault, it’s that it’s almost too forensic. Quirjin de Lang (Sam) and Wallis Giunta (Dinah) don’t merely look their parts. De Lang’s voice darkens and deepens as he indulges his locker-room delusions, and after two tightly controlled stanzas of hopes and dreams, Giunta’s mezzo-soprano fills out vibrantly, heartbreakingly, when she recalls the early days of their courtship. Much of Trouble in Tahiti comprises monologues, and the way Eberhardt frames them makes the whole thing feel more like a revue than an opera. But with whip-smart orchestral playing under Tobias Ringborg, plus that terrific vocal trio chirpily slipping their off-the-shelf optimism into the place where the protagonists’ inner life should be, it all sort of works. And boy, is that jingle catchy.

As part of Opera North’s ‘Little Greats’ (a season of one-acters), it was paired with Janacek’s Osud: a real rarity, though the score has that unmistakable Janacek immediacy, and the life-becomes-art plot is affecting. John Graham-Hall was touchingly awkward as the composer Zivny; Giselle Allen radiated ardour as his wife Mila, and Rosalind Plowright had a broken dignity as Mila’s mother (another of Janacek’s grotesque operatic in-laws). The orchestra, under Martin André, was raw, headstrong and occasionally ragged. All to the good — if you cut Janacek’s music, it should bleed.

Yet somehow Annabel Arden’s new staging didn’t quite land its emotional punches, on this first night at least. The pacing felt slightly off, and the central catastrophe — the ‘lightning from a blue sky’ on which the whole drama pivots — fell flat. Arden added a framing device: an unnecessary complication in a plot that’s already like a box of mirrors. And the scruffy sets (shared, or so it appeared, with ON’s current Cavalleria rusticana) didn’t exactly help create the Moravian spa-town atmosphere of the bustling first scenes. Still, Janacek sketches in so many characters so quickly that any director would have a tough job clarifying who’s who and what’s actually going on.

And better a near-miss from an ambitious company, visibly straining its resources to do something innovative, than the money-no-object bling of the Royal Opera’s Les Vêpres siciliennes — a luxury revival of an opera that even Verdi felt was third-rate, directed by the currently chic Stefan Herheim. A colossal reproduction of a Victorian opera house slides imposingly about the stage, and at one point the house lights are turned up and the company glares at the audience, fearlessly making the point that this is a 19th-century grand opera and we’re all watching it. Who knew?

Resistance felt futile. This is a thrilling cast: a truly heroic tenor, Bryan Hymel, as Henri; Malin Byström singing with dark, volatile brilliance as his vengeful beloved Hélène; and Erwin Schrott (Procida) exuding weapons-grade charisma as he hoses us down with the kind of creamy, 80 per cent cocoa-solids bass tone you thought they didn’t make any more. They sparked off each other too, while Maurizio Benini’s urgent, expressive conducting could almost (almost) have convinced you that you were hearing Don Carlo. And all the time, ballerinas whirled about and those gleaming sets kept trundling into ever more eye-popping new configurations. The gold-braid budget alone looked as though it could have funded Opera North’s entire season. Ladies and gentlemen, your taxes at work.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in