Jihadi Culture might sound like a joke title for a book, like ‘Great Belgians’ or ‘Canadian excitements’. But in this well-edited and serious volume Thomas Hegghammer — one of the world’s foremost experts on jihadism — has put together a collection of essays by an impressive group of scholars analysing what culture Islamism’s most adamant adherents might be said to possess. The book is not a long one.

Designed for a primarily academic audience, Hegghammer’s introduction carries all of the baggage that such audiences demand. It is not writing so much as a set of pleas and signs sent out to academia’s own hostage-takers, who lurk in universities and colleges reading mainly for the hope of discovering a rival’s error. Thus things that are not going to be included have to be highlighted and their exclusion justified in advance. Terms and definitions need to be exhaustively agreed upon with due acknowledgement that agreement may not be reached. And so on. Perhaps one of the reasons why western academia has had so little to say on this most important issue of our times is not only a lack of courage or expertise but the fact that academics find it so hard to avoid standing at the starting blocks and discussing them as though they are the race.

The present volume contains essays on jihadi poetry, a cappella songs (known in Arabic as anashid), visual culture and cinematography. If I had a definitional objection of my own here it would be that it is hard to say where these traditions vary or are particularly distinct from wider Islamic and Arabic culture. Dream interpretation, for instance, is a wide enough tradition in Islamic societies, and it is not obvious where jihadist dream interpretation is especially distinctive.

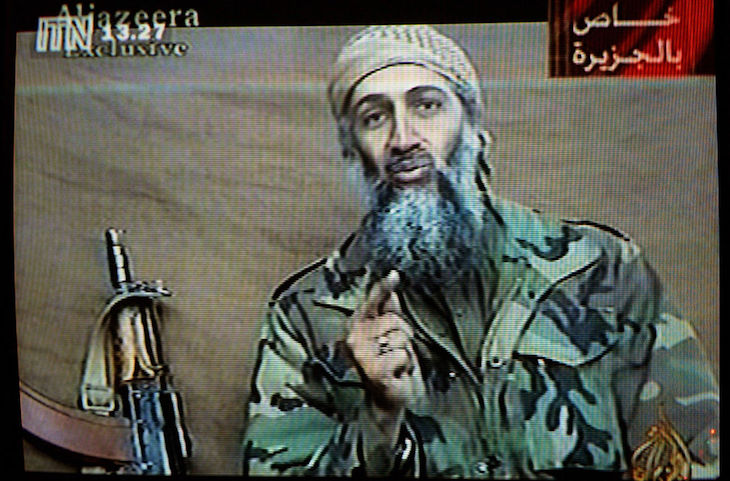

Nevertheless, Osama bin Laden and other jihadist leaders have certainly been interested in the subject. In late 2001 Bin Laden spoke about a follower who had dreamt ahead of the 9/11 operation that he was playing a soccer game against America and when his team showed up they were all pilots and won the game. Bin Laden claimed the follower (Abu’l-Hassan al-Masri) had known nothing of the operation but that the dream ‘was a good omen for us’.

In general, little about the culture revealed by the contributors is very surprising. Nor is any of it deep enough to engage beyond its own terms. As with the volume Poetry of the Taliban, published a few years ago, there will be scholars and amateur apologists who argue that some rich tradition is contained herein — something surprising, or even humanising. Readers can judge for themselves. In their excellent chapter on poetry in jihadi culture, Robyn Creswell and Bernard Haykel quote the Isis poetess Ahlam al-Nasr. Though an interesting figure for anthropological study, no one could say that her poetry rewards re-reading. A typical example of al-Nasr’s work is her poem commemorating Isis’s taking of Mosul. It’s the usual stuff. ‘Shiite infidels have reaped the rewards of enmity;/ the cross is broken and disgraced.’ The jihadis are ‘lions’ and so on. Original imagery and fresh similes are not the point of such work.

In the chapter on anashid there is a rather touching academic pie-chart showing the distribution of topics in a sample collection of such songs. Nobody will be surprised by the top subjects: jihad, Islam, liberating Palestine, liberating other countries, eulogising jihadis, lamenting the situation of the Ummah, mothers and so on. As with all other jihadi ‘culture’ the key elements are wholly predictable. First there is the repetition of familiar Islamic religious tropes. Secondly, the addition of an especially wanton form of sectarian bloodlust. Then added into this cocktail comes what we all know to be a key character trait of all despots and would-be despots: a type of mawkish sentimentalism, often centred around some variety of self-pity. Of course none of this is really culture as most of us would define it. A point worth making not merely because the aim of such ‘culture’ as jihadis have is to destroy all such culture — from Nineveh to London — as the rest of humanity possesses.

What Hegghammer’s authors generally analyse as the culture of jihadis is in fact merely some of the less famous ways in which jihadis rile themselves and each other up: it is more utensil than art. One typical line of a song used to fire up the jihadis goes: ‘It is the need of the time that we take a sword in hand, and crush the worshippers of falsehood.’ Analysis of the musicological element is superfluous, as any harmonic interest in these songs is self-hobbled: Islam — and especially the forms of Islam followed by jihadists — is even more wary of the power of music than Augustine of Hippo and John Calvin were in their tradition. The jihadis distrust music for the same reason they distrust women and art: because at some not very deep level they fear, correctly, that they are perverts.

It remains worth studying even the most apparently recherché aspects of their behaviour, not as an end in itself, but because doing so may yet give civilisation a quantitative advantage over its most conspicuous present foes.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in