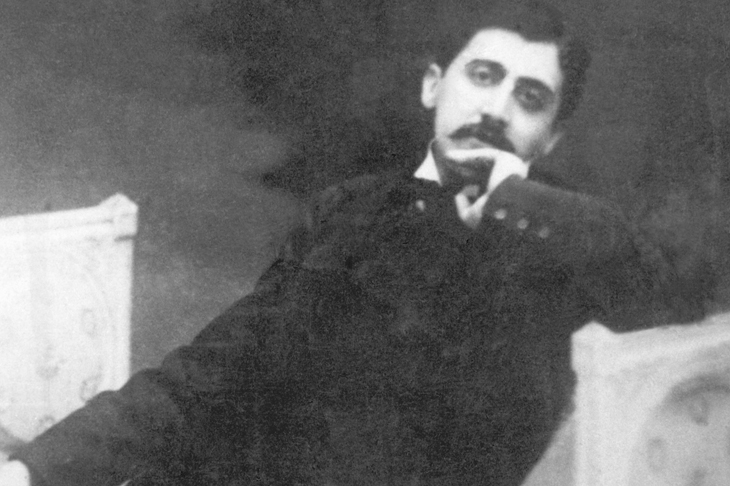

Why would a writer like Marcel Proust, who quivered and wheezed at the slightest sensation, decide to live surrounded by neighbours in one of the busiest parts of Paris? In 1906, at the age of 35, shortly after the death of his mother, he moved to a first-floor apartment at 102 Boulevard Haussmann. ‘I couldn’t bear to live in a place that maman never knew,’ he explained.

For this ghostly comfort, he paid a heavy price. Petrol fumes and tree pollen — to which he was almost fatally allergic — drifted up from the boulevard. In the absence of maman’s goodnight kiss, he sedated himself with valerian and heroin, but there was no escaping the blaring of klaxons, the thud of demolition and the renovation of his neighbour’s toilet: ‘She keeps changing the seat — probably having it widened.’

These 26 recently rediscovered letters were written by Proust to another neighbour, Marie Williams, the French wife of an American dentist who lived above him on the second and third floors. In their excruciating politeness, they take us to the heart of his sensory hell. Touch, taste and smell are the senses usually associated with Proust: the episode everyone remembers from his seven-volume novel, In Search of Lost Time, is the spongy madeleine which, dipped in a cup of tea, resuscitates the past by the miracle of involuntary memory. But the narrator’s ears — ‘anxious’ and ‘hallucinating’ — are just as active in the story as his nostrils and tongue.

Settling in to the apartment where, incredibly, he lived for more than 12 years, trying to write his novel, Proust faced the common dilemma of what the translator Lydia Davis calls ‘a noise-phobic’. He could either try to ignore or try to stop the noise. But if either attempt should fail, the noise would become even more intolerable. The nailing of packing crates, the arias of house painters, the inexplicable tap-tap-tapping of the servant upstairs would be laced with imagined malice and amplified by indignation.

Before the arrival of Dr and Mrs Williams, heavy hints seemed to be the best option. Dr Gagey, whose building work blighted Proust’s first weeks in the apartment, was asked up from the floor below to give his medical opinion. Proust had inserted something in his ear to stop the noise; the plug had stuck, and his ear (still otherwise functioning) was now infected. With the neighbours above, he tried a more subtle approach: he would smother the ‘admirably talented’ and ‘charming’ Mrs Williams, who played the piano and the harp, with flattery and flowers. He would be more than happy to contribute to the workmen’s wages if they could do their hammering at a less disruptive hour.

I am not sure that the editors and translator of these letters quite understand the ghastly complexity of Proust’s noise-abatement strategy. His tip-toeing phrases impress Lydia Davis with their ‘grace, eloquence, thoughtfulness [and] sympathy’, while the preface by Jean-Yves Tadié promises a tale of ‘friendship between two solitary [that is, lonely] people’. But anyone who thinks of buying this pretty little book as a hint to a noisy neighbour should know that Proust’s would-be discreet references to ‘torment’ evoke a grimace of rancour and rage. In 1915, he told Mrs Williams about a fruitless visit to one of his many friends. She must have wondered why he was telling her about this, until she reached the end of the sentence: ‘I mistook the floor, and the elevator went up to the top, causing me to do the opposite of what the Doctor’s clients do each day ringing at my door.’

To find noise distracting is not a ‘phobia’: this would imply an irrational disorder. No writer would find anything pathological in the fact that, for Proust, the bombs falling on Paris were less distressing than the sonic missiles which penetrated the walls and floors every day of the week, including Sunday:

Tomorrow is Sunday, a day which usually offers me the opposite of the weekly repose because in the little courtyard adjoining my room they beat the carpets from your apartment, with an extreme violence. … I hope that you will not find me too indiscreet and I lay at your feet my respectful regards.

One question taps repeatedly at the mind while reading these letters: does writing always have to be a torment? Even in the countryside, Proust found ‘the faintest sound more resonant than the racket in a Paris street’. The moments of undiluted joy which are the high points of his novel could only come from years of distraction, exasperation and despair of ever finishing. Then, in the sudden silence of memory, and perhaps only there, the ‘call of the car horns’ and the perfume of petrol fumes would summon up a blissful ‘picnic in the country and boating on the river, under the shadow of the trees’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in