As the saying goes, if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. So naturally, when the Race Discrimination Commissioner, Tim Soutphommasane, decided last week to share his view of Trump, Brexit, and conservative populism, he described it as ‘xenophobic and racist’. In the name of ‘equality and non-discrimination’ and ‘rationality and civility’, the populism that has swept the West should be shunned, if not made unlawful altogether.

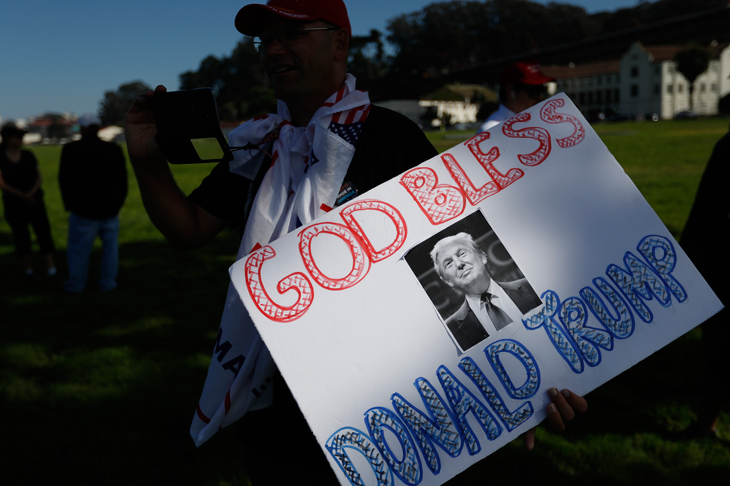

In the speech given to the Australian Political Studies Association, Soutphommasane argues that while there is a place in democratic politics for a populism of ‘benign authenticity’, the current wave is better characterised as ‘associated with nationalism, xenophobia and racism’.

Conservative populism is attributable to ‘cultural anxiety… felt by those who believe they are losing their place in society’s hierarchy’. According to Soutphommasane, that is why it is preoccupied primarily with immigration and multiculturalism.

Towards the end of the speech, Soutphommasane raises s. 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act which renders unlawful any speech or act that offends, insults, humiliates or intimidates someone on the basis of his or her race. For Soutphommasane, the law ‘strikes an appropriate balance between freedom of speech and freedom from racial vilification’. In line with this example, he concludes that the proper response to conservative populism is to be steadfast in the insistence that, ‘if people don’t wish to be called racists or bigots… they should begin by not doing things that involve racism or bigotry’.

Like all good tricks, the sleight of hand involved here might not be immediately apparent. But read properly, Soutphommasane’s argument is a call for the censorship of conservative populism. If it seems this is an exaggeration, complete the following syllogism: racism should be unlawful, conservative populism is a form of racism, therefore…

The key move in this argument is the slanderous conflation of conservative populism with racism.

To make his case, Soutphommasane adduces Brexit, Trump’s high level of support among white Americans, Pauline Hanson’s ‘opposition to immigration and Islam’, and the racist crime at Charlottesville, Virginia. Soutphommasane thus lumps together a vote for independence from an unaccountable supranational bureaucracy, the voting patterns of largely unrelated individuals, and the antics of a nonetheless legitimate representative of one of the world’s finest liberal democracies, with neo-Nazi terrorism.

For Soutphommasane, the thread linking these events is a desire to maintain a position of supremacy and privilege in society. This evocation of structural racism conveniently allows him to ignore that it is precisely this analysis of society with which populists take issue.

In the speech, Soutphommasane denies that populism is a legitimate reaction against identity politics — ‘and what commentators really mean here is multiculturalism’ — arguing that it is unclear in what way the ‘recognition’ of minority identities might have ‘gone too far’. He therefore fails to consider the real problem that conservative populists see in identity politics, which is that it is killing the national unity that sustains our political and cultural institutions, including freedom of speech and the rule of law.

Instead of being treated the same by an impartial system of law, under identity politics everyone is assessed in terms of various identities supposedly oppressed by our traditions, political system, language, and everything else we might once have considered unifying. Increasingly, the state takes upon itself the role of identifying societal groups and attempting to equalise their outcomes. Such thinking is behind everything from multicultural centres for immigrants to separate courts for Indigenous offenders to calls for gender quotas in private organisations.

In practice, identity politics means that the justness of an individual’s actions is determined by his or her situation in society. Soutphommasane’s dismissal of 18C opponents is indicative: ‘[their] ranks… appeared not to contain many who had lived experience of being subjected to racial vilification’.

The irony, and untenability, of Soutphommasane’s argument is that it makes positive demands on individuals to accord more power to the state, but in doing so undermines the shared identity and mutual trust that would make that possible. If each of us belongs to various castes, and politics is always an expression of hierarchy, then there is no reason for any of us to cooperate. Identity politics divides us, then demands unity.

Soutphommasane reiterated his longstanding defence of the need for patriotism, by which he only means a love of country that extends to the formal political institutions that govern us. But denuded of their attachment to a network of custom and tradition, our political institutions cannot command our loyalty.

It is only a thicker national identity, one that recognises our institutions as products of a particular heritage, that can support the modern state. On the conservative analysis, our institutions have emerged over our unique history to protect our rights and interests, and in doing so they help to shape and reinforce our shared identity, which in turn enables the empathy upon which liberal democratic society depends. Love of country comes from attachment to cultural particulars, not to abstract political philosophy and definitely not from mutual subjection to the machinations of politicians and their commissariat of charlatans.

It is unfair and unbecoming to simply dismiss the conservative argument about the provenance of our freedoms and formal equality as racism. And it is even worse to imply that it is a case that ought not to be heard, especially when one is a functionary discharging a law that is a proven tool of political censorship.

Soutphommasane did not spend much time in his speech discussing the anti-elitism of conservative populism. That is a shame, because it is bureaucrats like him aggregating to themselves responsibility for determining who shall have rights and who shall not that, as much as anything else, has provoked the anxiety that he diagnoses. If Soutphommasane wants an explanation for the origins of populism, he need look no further than his own lucrative office, which seemingly exists for no reason other than to condescend to the rubes who sustain it with their taxes—which they pay, yes, out of their sense of duty to the nation.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in