It took a spate of air disasters in the late 1970s, in particular the Portland crash of United Airlines Flight 173, for aviation experts to pay attention to something called Crew Resource Management. This is a set of procedures first conceived by Nasa with the aim of minimising human error in flight.

UA173 — where the pilots had spent so long fixated with a dodgy landing wheel that they failed to notice they’d run out of fuel — was one of a growing number of incidents in which disaster arose from failures in crew interaction. As with the Tenerife airport disaster and the Air Florida crash in 1982, there was no shortage of experience on the flight deck. The root cause lay not in the behaviour of the individuals but in the interplay between them.

Cockpit voice recorders revealed that, before some catastrophic decision had been made, a junior member of the crew had often voiced sensible reservations but did so diffidently in deference to his superior. It may seem strange that people would risk a gruesome death to avoid the social solecism of disrespecting their boss, but that’s the kind of hierarchical monkey we are. (Co-pilots of the day jokingly referred to their role as ‘the Captain’s Sexual Adviser’: every time a co-pilot opened his mouth, the captain would typically reply: ‘When I want your fucking advice, I’ll ask for it.’)

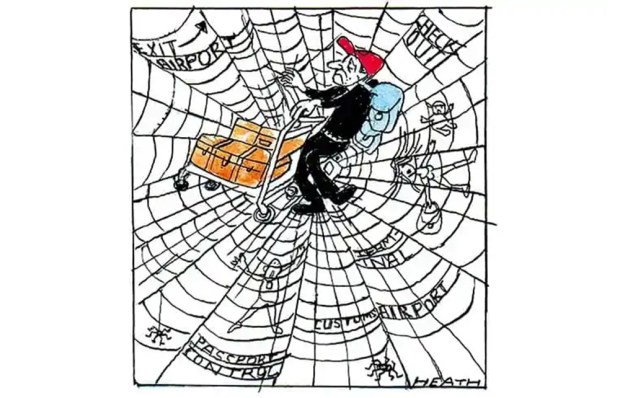

Since the 1970s, airlines have fostered a more collaborative cockpit culture, with marked success. Sadly, it hasn’t been adopted on the ground. Too little thought is given to finding better ways for humans to divide and share responsibilities, and to arrive at better outcomes collectively than they would individually. Take the stipulation that Brexit negotiations take place sequentially. This is the equivalent of demanding someone agrees a price for a car without being allowed to see it: it is either wilful sabotage or monumental stupidity. But it is far from rare: one Lufthansa aviation expert studied decision-making in hospitals. Her verdict? ‘If airlines were as bad as this, we would lose a plane a week.’

It would be a missed opportunity if no one from the aviation industry were asked to advise on the Grenfell Tower inquiry. While it is possible that the cause lies in corruption, greed, incompetence, poor regulation or an obsession with environmental benefits at the expense of safety, it is also perfectly plausible that the problem arose from poor decision-making structures, rather than any single fault.

The Royal Institute of British Architects believes the scope of the inquiry should be expanded to include new practices of procurement in the building sector, which have deprived architects and engineers of final responsibility for specifying materials.

My knowledge of the construction industry is minimal, but RIBA’s concerns about procurement practices ring true. They would seem to mirror a wider malaise in business whereby the final say in any decision goes to a department whose sole remit is often to meet a preconceived, narrowly defined specification at the lowest possible cost. In some cases the process is such that, should a bidder have a good idea for improving this specification, the procurement people will insist on sharing it with all other bidders in the interests of ‘transparency’. This generally means nobody questions anything.

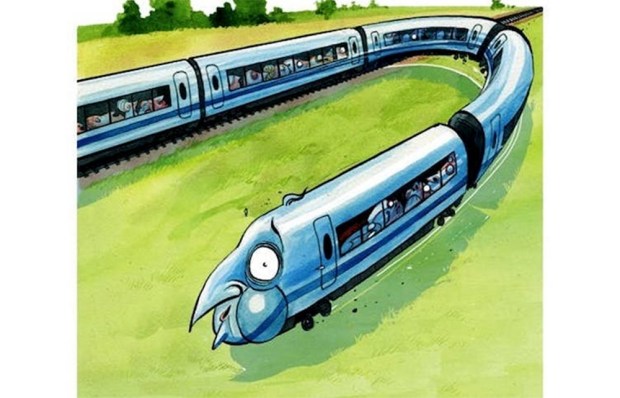

Procurement obviously deserves a major say. But not the final say. In aviation, great savings are to be made by loading aircraft with as little fuel as possible to save on weight. But the last word on fuel levels rests with the captain, not a finance function. He’s the one sitting at the front of the plane.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in