With the entrance to The Lodge turning into something of a revolving door since prime minister-elect Rudd bestrode the victory stage a decade ago today on 24 November 2007 there is no question the Howard years are remembered by many Australians as a golden age of political stability. It does not require a pang of misty-eyed nostalgia, however, to realise that the country, by any reckoning, was served by a remarkably effective period of governance under a conservative yet reforming prime minister whose term came to an end a decade ago.

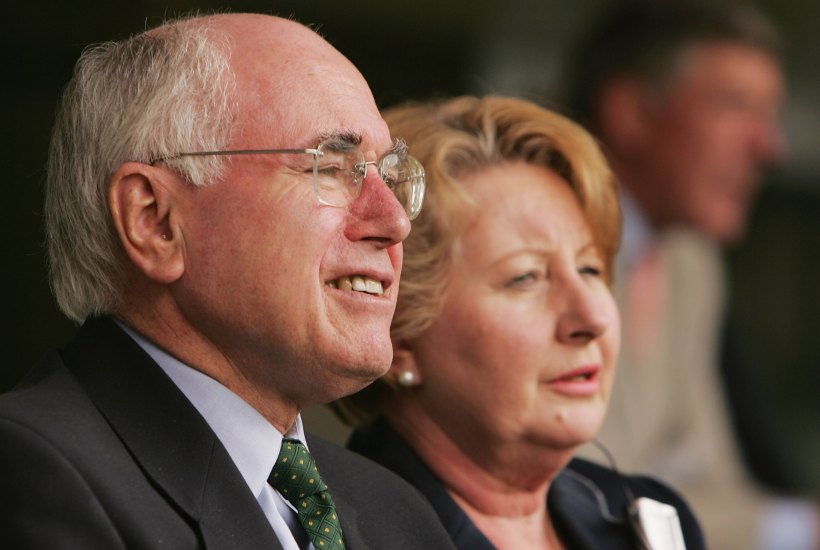

The figure of Howard still looms large in the popular memory as a busload of high school students to Old Parliament House last week feted the national leader of their early childhood. While his legacy continues to invite legitimate debate from all quarters of the electorate, the former prime minister is held in high esteem by the Australian public at large for the steady hand he brought to government and for the sustained period of economic growth and prosperity his government helped deliver.

On the night of his defeat, some commentators had prophesised that the Howard era came to an ignominious end where the achievements of his government would soon be buried and discredited. Three days after the 2007 election, however, the historian Geoffrey Blainey presciently observed: “In the end, John Howard will be seen by vast numbers of Australians as one of the great prime ministers”.

Since the Menzies era, the record and achievements of Howard remain unsurpassed by any other centre-right leader of Australia to date. Following his electoral triumph in March 1996, Howard seized the opportunity to lead a proactive and reformist government committed to further modernising the Australian economy. The decidedly bold reform approach of the Howard government paid dividends with the economy markedly improving on just about every indicator from unemployment to inflation during his term in office. Indeed, the economic policy achievements of Howard and his government, alone, earn him a secure place in the upper league of Australian leaders.

As well as enabling Australia to flourish economically and socially, Howard’s other great contribution to public life was that he gave both his own Liberal Party, and Australia at large, a surer sense of itself and the values it stood for. Again, since Menzies, Howard emerged as the most authoritative voice of Australian Liberalism that was able to communicate to the public, the principles, values and aspirations that the modern Liberal Party embodied.

Howard frequently explained to the Australian public that the Liberal Party, as a “broad church”, represented a synthesis of both classical liberal and conservative thought. According to Howard, Australian liberalism was at its best when it accommodated both these strands, bringing classical liberalism to bear more on economic policy and the conservative tradition more on questions of social policy and cultural identity. With salutary lessons for today, the prime minister brought a degree of unity, cohesion and purpose to the Liberal Party that it had not enjoyed since the early years of the Fraser government.

Howard’s resolve to reassert the identity of his own Party extended to that of Australia at large. As an unabashed patriot, he was determined to see a united Australia proud of its origins and assured of its own national identity and place in the world. Instead of perpetual navel-gazing about its own identity, Australia needed to be inspired by the best of its past. From the Federation project to the spirit of Anzac, the nation could celebrate the demonstrated virtues of liberal democracy, a classless egalitarianism, a “practical mateship”, and the ideal of a “fair go”.

Desiring Australia’s first people to be reconciled with the nation at large, he believed this was best accomplished not by mere tokenism but by forward-looking, practical measures to improve the daily lives of indigenous Australians. For Howard, the influx of millions of new arrivals since 1945 did not suggest Australia was simply a land of disparate tribes, but a family drawn from the four corners of the earth united by a common canon of Australian values.

Far from viewing Australia’s British heritage as a handicap to the nation’s engagement with Asia, Australia’s projection of Western civilisation into the Asia-Pacific enabled it to cherish its historic affinity with the UK and the US at the same time as forging close, friendly ties with its near neighbours. As prime minister, Howard possessed a definitive sense of what Australia and its people represented and what they could aspire to be.

Together with Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan and Helmut Kohl of Germany, Howard also ranks as one of the great centre-right leaders of the modern Western world. With his ascendency in 1996, he brought this great renaissance of the centre-right to the South Pacific and became one of its chief standard-bearers in the 1990s and 2000s. In the same vein as Thatcher, Reagan and Kohl, Howard worked to advance the ideals of liberal democracy, the freedom of the individual and the need for a strong, job-creating economy to be fuelled by individual initiative and free enterprise.

His government succeeded in calibrating this agenda to the Australian setting by instituting industrial relations reforms to the Australian waterfront and workplace, by reforming the Australian taxation system to make enterprises and industries more competitive and by brokering free-trade deals with Australia’s major trading partners. Like the experience of his North Atlantic counterparts, his programme of economic reform arguably made Australia more strong, free and prosperous over the longer term. Indeed, the stature of Howard as a modern conservative reformer was such that he became a model and mentor to succeeding centre-right leaders such as New Zealand’s John Key and Stephen Harper of Canada.

As the Australian electorate collectively yearns for a return to stability and direction, leaders on all sides of the political fence could do worse than emulate John Howard’s combination of philosophical conviction and adroit policy pragmatism that delivered the goods.

David Furse-Roberts is a Research Fellow at the Menzies Research Centre and is editing a volume of speeches by former Prime Minister John Howard to be released in early 2018.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in