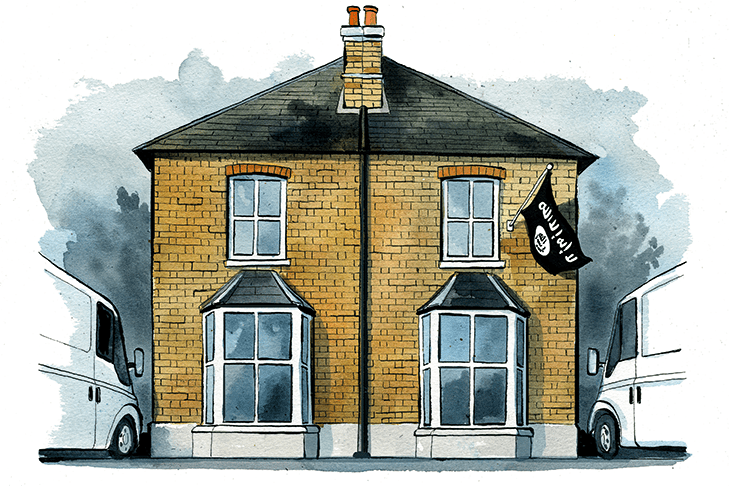

In normal times, the reported return of 400 Isis fighters to Britain would be the biggest story out there. But with policymakers preoccupied by Brexit, and the press examining the sexual culture of Westminster, this news has not received the attention it deserves.

The return of these fighters has profound implications. The security services are struggling to keep up with all the possible terrorists at large. Notably, Andrew Parker, the director-general of MI5, has warned that plots are being devised at the fastest rate he can remember in his 30-year career. Though he stressed that the security services have prevented seven attacks since March, he also said they cannot foil every effort.

This is simply down to capacity. A frequent feature of recent terror attacks has been that the perpetrator had appeared on the security services’ radar, but that they hadn’t been under close surveillance because they weren’t an immediate threat. The security services have the ability to monitor only about 3,000 people at any moment. So there are around 20,000 people who have previously been investigated but are not currently being watched. Add a returning hard core of several hundred — who will undoubtedly radicalise others — and you can see how this problem becomes even more unmanageable.

The obvious answer to this question is for the state to do everything it can to locate the returnees and lock them up. Islamic State is a murderous death cult. Why should people who chose to leave this country to work with such a murderous group be treated with anything but the utmost severity?

But strangely, some are making a more lenient case. Max Hill QC, the government’s independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, recently argued that it was right not to prosecute all of those who had joined Isis. He said that those who had ‘travelled out of a sense of naivety, possibly with some brainwashing along the way, possibly in their mid-teens and who return in a sense of utter disillusionment’ should be kept out of the court system.

This is a naive remark, to say the least. We struggle as a society to understand that Islamist extremists really mean it. Their ideas seem so alien to us that we think we must have misunderstood them. Even when they leave this country and travel to Syria and Iraq to join forces with fanatics, we fail to let their decision speak for itself. But who could have been confused about the true nature of Islamic State?

It is overwhelmingly in the public interest to prosecute those who went to link up with Isis. First, it is important for the sake of justice itself. Those who aligned themselves with this group should face the legal consequences. Secondly, it is important as a deterrent. The idea that you can sign up with a terrorist group which is fighting, among others, the British military — and beheading British and Syrian civilians — but not be prosecuted is extremely harmful. Then there is community cohesion to think of. It would be a gift to the far right if they could claim that many who had gone to fight with Isis had just been allowed to come back home unimpeded.

It is not just on this matter that Hill has been naive. Last Friday, he met with Cage — a fringe Islamist group whose research director referred to so-called ‘Jihadi John’ as ‘a beautiful young man’. Hill has written in defence of his decision, arguing that he is not part of the government, needs to hear what everyone thinks of anti-terror laws and has noted that his predecessor saw Cage. But by sitting down with them, Hill lends Cage a credibility they don’t deserve. His decision to see them so early on in his tenure makes them look like leading actors in this debate, rather than the fringe figures they are. One is left wondering what possible proposals Cage could make that Hill would want to listen to.

His remit doesn’t extend to the counter–extremism Prevent programme, as he acknowledges. But Hill’s foreword to a report by the NGO Forward Thinking comes close to climbing on the band-wagon of criticism of this vital effort. He writes: ‘Whilst I always made clear that I do not accept that Prevent is a “spying” programme, it was clear to me that these community concerns are deep, they are prevalent across the country and urgent attention is required to address them.’

There is huge frustration in government at Hill’s behaviour. When it appointed the lead prosecutor of the 21/7 attackers to this job, it was not expecting grandstanding. As one senior government source laments, the previous reviewers of terrorism legislation ‘got down to the job and explored everything in private before going public. He does the whole Twitter thing.’ There is a sense in government that Hill is straying beyond his brief. As one Home Office source puts it pointedly: ‘He doesn’t do policy.’

What is more worrying is the sense that the government has lost clarity on the Islamist threat. By the end of David Cameron’s time in government, Downing Street was doing a good job of ensuring that the government didn’t undercut moderate Muslims and reformists by engaging with even non-violent exponents of grievance-mongering Islamist ideology. Since Cameron’s resignation, much of that focus has gone. The problem has been compounded by the departure of May’s two chiefs of staff since the general election; they had been with her at the Home Office and were familiar with the issue.

Combatting Islamist ideology in the United Kingdom is one of the great challenges of our time. It should give this country pause that so many hundreds of Britons were tempted to go and fight with Isis. Ultimately, the only way to reduce the number of potential terrorists is to deal with the problem upstream. Theresa May must be true to the commitment she made after the London Bridge attacks — that ‘We cannot and must not pretend that things can continue as they are. Things need to change.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in