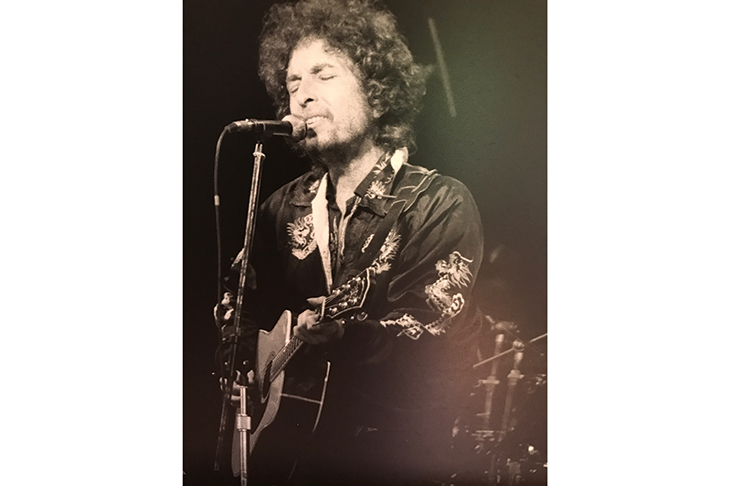

‘There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.’ Lord Henry Wotton said that. It is always better to read Bob Dylan than to read about him. I said that.

Two new books by Dylan, and two about him, prove my point. Just out in a lovely slim hardback is Dylan’s Nobel lecture (Simon & Schuster, £14.99). Its 32 pages have already been well picked over and much written about, but Dylan’s own account of the way he took ‘folk lingo’ and ‘fundamental’ literary themes — by way of Moby-Dick, All Quiet on the Western Front and the Odyssey — to write ‘songs unlike anything anybody ever heard’ should be both read and heard. There are differences in the recorded and printed version to keep fans and Dylanologists busy, of course; is it ‘Lord Donald’ or ‘Lord Darnell’, more likely, whose ballad he invokes? A signed limited edition of the lecture can be yours for £1,900 or so.

100 Songs is a selection made not by Dylan himself but by the publisher (Simon & Schuster, £14.99). It performs the difficult feat of presenting only that number of original songs from a canon of close to six times this. Beginning with ‘Song to Woody’, written by a 19-year-old for Woody Guthrie, the dying hero he came to New York City to find in the frozen early days of 1961, and ending with four songs from Tempest (2012), the collection spans Dylan’s professional career of six decades, and counting.

According to a recent interview in Harvard Magazine, Richard Thomas, the George Martin Lane professor of classics there, ‘sat down at his keyboard a couple of weeks after the announcement last fall of Dylan’s Nobel prize in literature’. He finished Why Bob Dylan Matters six months later (Collins, £12.99). ‘Why Bob Dylan Matters to Richard Thomas’ would be a more accurate title. The best parts of the book recount Thomas’s own autobiography in terms of a lifelong love for Dylan’s music — but much of his book attends to ‘the thefts and reworkings’ in Dylan’s writing.

Contributors to the Dylan website Expecting Rain have long been noting Dylan’s use of lines from other writers, including classical poets. Eyolf Østrem wrote about his paraphrase of Allen Mandelbaum’s translation of the Aeneid in ‘Lonesome Day Blues’ 15 years ago. Dylan contains multitudes, that is sure. But too much in Thomas’s book is speculative. The wild geese in ‘When I Paint my Masterpiece’ ‘likely refer to’ a story ‘bound to have been on the quiz shows of the Latin Club’ to which Dylan belonged for two years at Hibbing High ‘in which the sacred geese of the goddess Juno’ warned the Romans of attacking Gauls. Ahem: ‘geese’ also rhymes with ‘masterpiece’. It’s a song. And when Thomas insists on finding ‘intertextuality’ in the repetition of a single word — Rimbaud’s use of ‘ones’ in his poem ‘Poor People in Church’ and Dylan’s ‘ones’ in ‘Chimes of Freedom’; or Dylan and the Beatles using (very different) words of one syllable in ‘Fourth Time Around’ and ‘Norwegian Wood’ — he’s on shaky ground.

What Thomas neglects is how coolly Dylan stands on the shoulders of generations of giants: Shakespeare’s versions of classical plays; W.B. Yeats’s revisions of William Blake’s intense symbolism and allegories; Homer’s epics filtered through Byron and Joyce. That Dylan is a creative magpie has been old news since 1961. The world of folk singing is one of sharing, trading, teaching and learning songs that belong to no one and everyone. But he also, which is more compelling, obeys Ezra Pound’s Modernist dictum: make it new. What Dylan takes from writers (and artists and photographers) past is far less interesting than what he makes from it all, in the forge of his own imagination and skill.

Clinton Heylin, one of the most acclaimed and authoritative biographers of Dylan, turns in his new book, Trouble in Mind (Route Press, £16.99) to the ‘Gospel Tour’ of 1979–1980, exploring the events of the tour, its background and its aftermath. The extensive interviews with members of Dylan’s band, particularly his guitarist Fred Tackett, are grand accompaniments to surviving film footage of the tour.

Heylin’s greatest strength here is the breadth of his knowledge about Dylan’s other tours. He amasses a chronology for the ‘Gospel years’ composed of contemporary interviews and reviews and thousands of quotations, framed in his own writing. Heylin is a strong and often idiosyncratic writer, emphatically anglicising things like Dylan’s grabbing a smoke (a ‘fag’, in inverted commas), though he is not kind to the women on this tour. Clydie King is Dylan’s ‘paramour’, and collectively the backing choir are ‘girlsingers’. King was making records as one of Ray Charles’s Raelettes while Dylan was sitting at his desk in high school and Mona Lisa Young has recorded with everyone from Barbra Streisand to Bruce Springsteen. They’re no one’s ‘girlsingers’.

Anecdotes abound, and are wry, sly and telling: Dylan, looking at a signed photo of Springsteen (who Heylin describes as a ‘nemesis’ at the time) leaning against the hood of a car, and asking ‘That guy still driving that stolen car?’ Fred Tackett, recalling Dylan’s wearing all Willie Smith’s silk Hawaiian shirts and putting them back in Smith’s wardrobe unlaundered. Concluding a detailed discussion of Jann Wenner’s 1979 review of Slow Train Coming, Heylin says: ‘For once, a Stone review mattered.’ For flourish, facts and transcriptions of Dylan’s religious speeches from his stages, and a fine complement to the just released recordings of Dylan’s official ‘bootleg series’, Heylin’s your man.

But Dylan remains at a remove from all these post-Nobel ink-spills, on the road somewhere. Emily Wilson’s new translation of the Odyssey speaks of ‘a complicated man’ with an ‘old story for our modern times’. She might be singing of this original modern vagabond — wanderer, laureate and so much more.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.