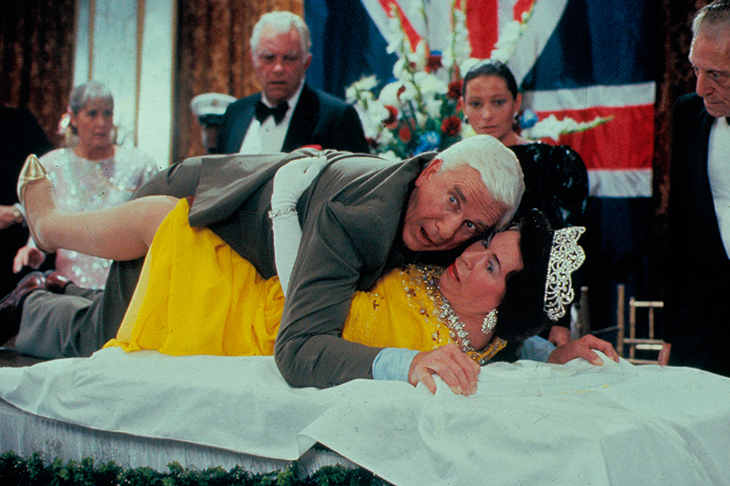

If cinema is propaganda, Elizabeth II can be grateful to it. Film is a conservative art form, and almost nothing has attempted to thwart or mock her. (The Daily Star once printed that Princess Margaret would appear in Crossroads, but Crossroads was not cinema, and it was not true. Instead the award for tabloid lie of the year was named the Princess Margaret Award.) I could not find an art film with the Queen weeping under a table in her nightgown, although she did appear in The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! (1988), and was mounted by Leslie Nielsen. She also appeared in the disaster film 2012 (2009), attempting to flee a tsunami in an ark built by China, with the dogs. This is less preposterous than the Leslie Nielsen scene. She would not go to China to die. But that is it. Spitting Image did more to damage her than Hollywood. A lot more.

The King’s Speech (2010), in which she appeared as a child, was mere submission. ‘Halting at first, but you got much better, papa,’ says the 13-year-old Princess Elizabeth (Freya Wilson) to her father George VI (Colin Firth) after he makes a speech to the empire without stuttering.

In The King’s Speech, Wilson establishes what is believed to be the Queen’s abiding characteristic, which she inherited from George VI: duty. She curtseys to her father and looks sadly at him, for she knows they are both cursed. The privilege is irrelevant. They exist for our benefit, and it is painful for them. There is also the usual subplot, in support of the ‘good Windsors’ — dreadful David (Edward VIII) and creepy Wallis — who did not do their duty and are consigned, as punishment, to the hell of café society and foreigners.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which is also conservative, responded by giving The King’s Speech four major awards: best film, director, screenplay and actor. The director Tom Hooper looked shocked. The last film to do that was Silence of the Lambs.

It is not worth asking whether cinema likes the Queen, because it clearly does; the only question worth asking is how accurate it has been.

For a long time, the definitive Queen was Helen Mirren in The Queen (2006), a film by Peter Morgan, who has made the monarch his life’s work. Morgan is really Morgenthau; Jews are often bewitched by the establishment. It tells the story of the crisis when Diana died. Mirren’s Queen is tall, slim and uneasy — she is not posh at all, but brittle, and nervy. The film surmises isolation — hers, not Diana’s — which may be true, but it is built on a lie, and the idea fails. The central metaphor is a stag, which the Queen sees near Balmoral; does she see herself in him? Does she see herself as beautiful, and hunted by bankers? It feels unlikely. When the stag is shot, she goes to visit his body, which is ridiculous. The Queen shot her first stag as a teenager; even so, the Academy gave Mirren the best actress award, possibly for being filmed in a dressing gown with curlers in her hair.

I did not believe in this queen at all. She was a victim, but the wrong kind.

Morgan is spikier in his play The Audience, which also starred Helen Mirren; there is one vicious insight in it. ‘Honestly, you lot and your “Scottishness”,’ Harold Wilson tells her. ‘Doesn’t fool me for a second. You should have someone playing the accordion in lederhosen. This place looks like a Rhineland schloss.’ They then talk wistfully about bungalows.

Morgan’s masterpiece is The Crown, for Netflix, with Jared Harris as George VI and Claire Foy as Elizabeth II. This Elizabeth is utterly decent, initially unsure of herself, and inspired by her grandmother Queen Mary. ‘While you mourn your father, you must also mourn someone else,’ Queen Mary (Eileen Atkins) tells her by talking letter. ‘Elizabeth Mountbatten, for she has now been replaced by another person: Elizabeth Regina. The two Elizabeths will frequently be in conflict with one another. But the crown must win. Must always win.’ This is drama, but it feels plausible. Elizabeth says she does not have a strong character, like others, but the crown has landed on her head, and there it is. Practical.

Alan Bennett could not resist projection in A Question of Attribution, a BBC play about Sir Anthony Blunt, in which he makes the Queen an intellectual — a female Alan Bennett, who could live in north London, wrapped in the London Review of Books.

Blunt removes a Titian from the wall; the conceit is that he thinks it a fake. As he is! Elizabeth (Prunella Scales) comes upon him with stealth, and fierce cleverness. She doesn’t want to be painted by Francis Bacon, she tells him; she doesn’t want to be a screaming queen. Bennett hints that she knows of Blunt’s treachery, as if she, the head of state, has some magical power to discern a threat to it; and this is true. In life, she had not trusted Blunt since he admitted his atheism to her. In 1951, atheist = communist.

In Steven Spielberg’s The BFG (2016) Elizabeth is, explicitly, a good witch in league with a big friendly giant, or BFG. The orphan Sophie (Ruby Barnhill), terrified by flesh-eating giants, sees a photograph of Queen Victoria in the BFG’s cave. ‘We are going to the Queen,’ Sophie tells him. ‘We really, really need her help.’ This film has no faith in liberal democracy. It is a fairy-tale, and it craves a benevolent autocrat, in Penelope Wilton.

This Elizabeth is witty, and humane, with the vision of a sorceress; she is a pre-medieval queen. She believes Sophie. She gives her, and the BFG, breakfast. Nothing surprises this queen, for she sees everything in heaven and earth. She sends in the army, and dispatches the flesh-eating giants to an island. But they will not be starved. Elizabeth gives them the seeds of a disgusting vegetable called a snozzcumber; she has delivered justice. The orphan Sophie, meanwhile, goes to live with the Queen, which is the most preposterous thing in any film about her. Impoverished children do not live in the palace. That is a myth, and a bitter one.

There is one final clue: her appearance as herself in a James Bond short for the Olympics ‘starring Daniel Craig and Her Majesty the Queen’. She didn’t get top billing, which may in itself be telling. Who is her agent?

The real Elizabeth, here, is patient, and faintly mocking; she is a constant. She is not fierce like Scales, or saintly like Foy, or anxious like Mirren. She is gaudily beautiful in pink feathers and sequins, for who is immune to Daniel Craig? As Disraeli wrote of Queen Victoria, ‘Remember, she is woman.’ Or is it just that she is appearing in a film, and film stars are pretty, and so she must be pretty too? Is it yet another piece of duty?

Elizabeth II has eluded cinema, then, as she has eluded us. We can choose from a variety of myths, and the most plausible, to me, is Foy in The Crown; and the most comforting is Wilton in The BFG. We can bounce off her silence because we all have a stake in believing in her; if not, what was it for? We see only — as Bennett did — the Queen we want to see, and that is worth an Academy Award.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in