If you work for the Church of England in any capacity, from Archbishop of Canterbury to parish flower-arranger, how do you deal with the distressing statistics that in the past 20 years, average Sunday attendance has plummeted to 780,000 and is going down by a rate of about 20,000 a year?

Do you pretend it’s not happening and just tell everyone about the spike in your numbers at Christmas, or accept that it might be happening but believe that God’s grace will deal with the problem in its own good time? Or do you throw your weight behind a vast national marketing initiative, hurling millions of pounds at the problem?

Are you, in short, a denier or a panicker? We must thank Bishop Humphrey Southern, principal of Ripon College Cuddesdon, for coming up with those two words to describe the people on opposite sides of the debate, which isn’t really a debate because the people on opposite sides are hardly speaking to each other. In the nicest, most prayerful Christian way, they can’t stand each other and will do their best to avoid each other at synodical events. The panickers think the deniers are steering the Church towards oblivion; and the deniers think the panickers are eroding and cheapening the Church’s whole character.

They would never, of course, call themselves either of those two terms. The ones branded ‘panickers’ argue that they are realists, addressing the pressing problem of how to get numbers and clergy vocations up so there will be a Church in 50 years’ time. Of the two types branded ‘deniers’, the ‘declining numbers’ deniers argue that ‘Those statistics don’t mention the millions who go to midweek services such as funerals’ or ‘Just come to my church in Sussex on a Sunday and you’ll see it’s thriving, numbers are actually up.’ The ‘God’s grace’ deniers argue that an obsession with numerical growth bears no relation to Jesus’s way of building the Kingdom of God, which was always to concentrate on quality rather than quantity.

Both sides spout Bible verses at each other. Deniers quote the verse from the Parable of the Sower: ‘Some seeds fell on stony ground.’ It’s all very well, they say, to be obsessed with ‘growing’ your congregation if it’s in an M25 Bible Belt parish full of trendy twenty-somethings. But in the middle of rural Herefordshire, you might need to be ‘picking out the rocks’ for several generations, and there’s no hurry.

Panickers also like to quote anything from the New Testament about seedlings or wheat. The strapline for the panickers’ task force report, From Anecdote to Evidence, was ‘I planted the seed, Apollos watered it, but God made it grow’ (1 Corinthians 3:6). That verse is repeated on every page, like a mantra. The findings of the report led to the setting up of the ‘Renewal & Reform’ programme, described on its own website as ‘an ambitious programme of work, which seeks to provide a narrative of hope to the Church of England’.

Through a complicated process of form-filling, dioceses can now apply for money from the Church Commissioners for parish projects that will grow their congregations. The Commissioners have undertaken, for the next ten years, to spend £24 million of capital a year on ‘strategic development’ and another £24 million a year on ‘mission and ministry in low-income communities’. Deniers say that by doing this they are robbing the future to pay for the present.

Who’s the driving force behind the panicker agenda? There’s no doubt it’s Justin Welby. It’s a fairly open secret that he got the job of Archbishop of Canterbury on the strength of his panicker thesis. All the candidates were asked to write a short mission statement saying ‘What I would do if I were Archbishop’. Welby, who had been Bishop of Durham for under a year and thought he had no chance of getting the job, penned something along the lines of ‘The Church of England is going down the tubes, there needs to be some drastic action and I’m the one to take it on.’ The Church of England Appointments Committee found his statement lurking at the bottom of the pile and pounced on it. ‘At last! The man who will save us!’

Having got the job, Welby sent out a church-growth task force to do its research, and launched the programme — and now, any just-about-managing clergyman or woman who’s running his or her eight parish churches, trying to minister to the congregation, is made to feel a failure if he or she isn’t also ‘prioritising growth’, ‘offering specific discipleship courses’ and ‘cultivating missional intentionality’.

When the task force asked clergy, ‘What kind of growth is your priority?’ only 13 per cent of them said ‘numerical growth’. The rest said ‘spiritual growth’ and ‘social transformation’. But from Church House’s point of view, that was not the right answer. Numerical growth must be prioritised. Dioceses toeing the line have now incorporated the word ‘growth’ into their own straplines: ‘Diocese of Lichfield: Going for Growth’, and ‘Diocese of Norwich: Committed to Growth’.

Mike Eastwood, the current director of the programme, tells me that ‘R&R’ has funded some exciting new projects, such as the new Gas Street church in Birmingham that has opened in an old warehouse and now attracts hundreds each week, and St Paul’s Shadwell, which was on its last legs but is now a thriving HTB (Holy Trinity Brompton) plant. Vocations are up by 14 per cent, he says, thanks to the new ‘bring along a potential ordinand’ parties held by bishops. ‘I don’t like the “the church-will-see-me-out” brigade,’ he says. ‘That attitude’s not going to work for much longer. The projections are that church attendance will be down to a quarter of a million by 2050. But we can turn it around and we will.’

The driving force behind the anti-panicker agenda is Professor Martyn Percy, Dean of Christ Church, Oxford. When asked, during an interview for an episcopal post, ‘So, what would you do to get more bums on pews?’ he replied, ‘I’m more interested in getting bums off pews. Seriously, we are not trying to grow the membership of a club; we are trying to send out people to further the work of the Kingdom of God.’ Shortly after that interview, he withdrew from the selection process, unimpressed by the ‘unimaginative cookie-cutter process’ of selection.

‘We are the few for the many,’ Percy says. ‘That is the way the Church has nearly always been: quality, not quantity. Worship and prayer always come first; then we see what happens after.’ He can’t bear the ascendency of ‘mission-minded middle-managers’ who boast about their shiny new projects with their flashy short-term results. He believes that the whole ‘my church is bigger than yours’ agenda can lead to narcissism on one side and depression and self-harm on the other. And he feels that the Church has totally turned in on itself in its obsession with numerical growth.

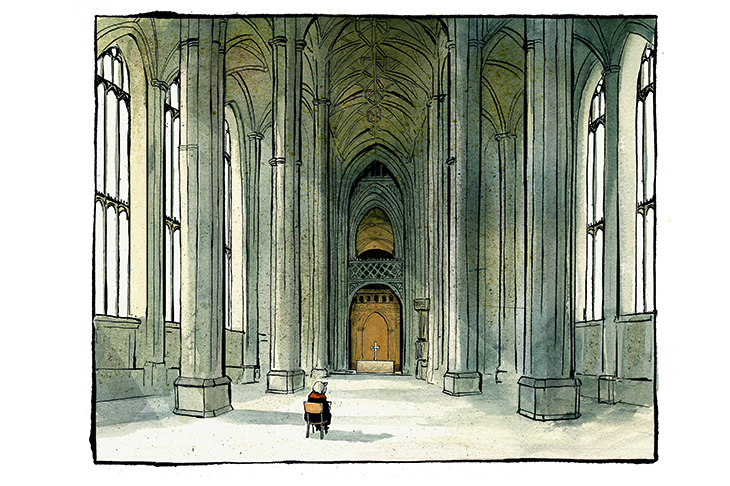

With his oil-industry and banking background, says Percy, Welby’s world has been shaped by capitalism. He’s applying brash marketing strategies to the C of E, which is moving from being a ‘support-based institution’ to a ‘member-based institution’. What the majority of people treasure about the C of E is that you don’t have to become a signed-up member. People don’t always want to be hugged and asked to fill in a covenanting direct-debit form. One reason why cathedrals are thriving is that you can go to them anonymously and you won’t be ‘mugged with an Alpha course’, as Percy puts it.

It’s true that panicker language is riddled with marketing speak: and worse, holy marketing speak. The language manages to combine a torrent of inoffensive abstracts, a wafty feeling of prayerfulness and a slightly threatening centralised agenda. ‘Disciple’ is used as a verb: ‘Will we determine to empower, liberate and disciple the 98 per cent of the Church of England who are not ordained, and therefore set them free for fruitful, faithful mission and ministry, influence, leadership, and most importantly, vibrant relationship with Jesus in all of life?’ thunders the R&R literature. Few would dare to answer ‘No’. But beneath the lines one can read, ‘Are we going to dragoon a whole lot of nice persuadable people to come and work for us for free? Yes, we are.’

Humphrey Southern’s hope is that those on both sides will start to talk to each other. At the moment, the panickers are refusing to countenance being ‘non-intentional’ – i.e. ‘just seeing how things go and rolling with it’. And deniers would prefer the church to die — literally — than turn into a shallow, self-satisfied members’ club.

What deniers fear most is that the panickers’ true aim, as they embark on this spending spree, is to stage a back-door ‘evangelical takeover’. It seems clear to deniers that these much-vaunted new funds are not promoting quiet, self-effacing ‘Catholic’-style worship, or choristors in ruffs; they’re promoting centres for instant conversion and worship songs. If the two sides are to open up to each other, the panickers will need to prove to the deniers that an evangelical takeover is not their hidden agenda.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in