To me, the strange words ‘Marsh Gibbon’ once meant I was nearly home. My heart lifted as we creaked and shuddered into the little station at Marsh Gibbon and Poundon, on the slow and pottering line between Cambridge and Oxford. Usually it was dusk by the time we got there, and I can remember seeing the gas lamps lit and flaring, a pleasing moment for anyone who likes a little melancholy.

But equally remarkable was the lowness of the platform. Had it actually sunk into the marsh after which the desolate little halt was named? I recall a withered, gloomy porter in a peaked cap carefully setting steps by the door, for the few passengers wanting to alight at this mysterious destination. Without him, they would have had to jump. I like to think he may have been the original of Puddleglum, the magnificently pessimistic and steadfast swamp-dwelling Marsh Wiggle in C.S. Lewis’s The Silver Chair. Lewis often used to travel by the line (he called it the Cantab Crawler). And it is easy to see how he might have got from ‘Marsh Gibbon’ to ‘Marsh Wiggle’.

The porter, as pessimists usually are, was right to be gloomy. By then I’d seen enough railways shut to know that this one was probably doomed as well. And so it was. Harold Wilson closed it in 1967, just after my boarding school days ended, even though Richard Beeching, the hated slayer of railways, had left it off his death list. For a child who loved trains the era was a parade of sadness. The grim notices of closure went up, like printed curses. There were hopeless protests. There was a last run. And then the slick men moved in, swiftly demolishing bridges and selling stretches of track to make sure it never opened again.

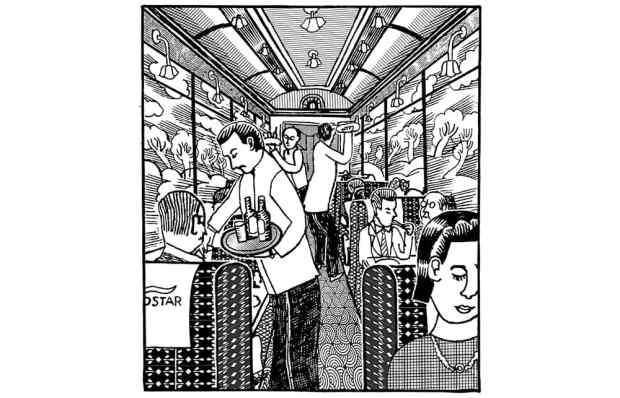

In this case the destruction was even stupider than usual. What nobody then called the ‘Varsity Line’ was one of the very few railways in England that went from side to side of the country, rather than up and down it. It connected almost every mainline out of London and would have been extraordinarily useful had they kept it. True, it was not rapid. It had many small stations, of the sort where milk churns sat in rows and the guard liked to chat with the stationmaster, who often maintained a cat. It was served by a weary dark-green diesel unit, not much more picturesque than a bus, which stopped so often that it never heaved itself above 40 miles an hour. You could make the journey between the two university cities more quickly by going into the capital and out again. But nobody aboard the Crawler was in a hurry. And on the journey back from school, especially at Christmas time, the retired, secret country through which it passed still had a glowing romance for me. Nowadays they call it the ‘Oxford-Cambridge corridor’, and seem to want to turn it into a sort of Home Counties California. I fear they will succeed.

But for a short while yet this largely unexplored piece of untouched England remains an agreeable land of mystery. John Bunyan tramped these handsome but not pretty fields, market towns, bogs and hills as he conceived his Pilgrim’s Progress. The Delectable Mountains are somewhere round here, as is the Hill Difficulty (I’ve bicycled up and down it). Even now you often feel as if you’ve fallen off the edge of the modern world. The station names — Claydon, Winslow, Fenny Stratford, Woburn Sands, Potton and Gamlingay, among many others — evoked a quiet, withdrawn, wholly English world of mouldering rectories covered in Virginia creeper, and slow, silent morose pubs where outsiders are tolerated but not welcome. Some of this is still true.

Since it closed, I have often walked or pedalled along its course, finding much of it needlessly neglected and overgrown, something which grew much worse after privatisation. If you did not know there had been a station at Marsh Gibbon and Poundon, you would never guess it now. I listen sourly and sceptically to vague, unfunded political promises — such as the one made last week — to reopen it. What I hear instead are plans to make the same mistake we made in the 1960s yet again — more roads, instead of the railway lines that are so perfectly fitted to our intimate landscape, and so cleverly and gently connect the ancient and the unspoiled to the modern and the busy.

A so-called ‘Expressway’ is planned, to fill the quiet nights and pastoral days of Bunyan’s England with the unending scour and snarl of motor traffic, and build box homes on top of the Slough of Despond. Will there never be anybody with any power who understands that the picturesque beauty of country railway lines is itself a national asset?

Peter Hitchens and Christian Wolmar on Britain’s lost railways on The Spectator Podcast.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in