Peter Paul Rubens thought highly of Charles I’s art collection. ‘When it comes to fine pictures by the hands of first-class masters,’ he wrote from London in 1629, ‘I have never seen such a large number in one place.’ In Charles I: King and Collector the Royal Academy has reassembled only a fraction of what the king once owned, yet even so this is a sumptuous feast of an exhibition. Some of what’s on show will be familiar to an assiduous British art-lover, since it comes from the Royal Collection and the National Gallery. But the sheer concentration of visual splendour is overwhelming and the installation spectacular.

The Renaissance, like spring, came late to northern Europe — and last of all to distant Britain. But in painting and architecture, it flowered briefly at the Stuart court. Charles persuaded two of the foremost living painters — Rubens and Van Dyck — to work for him and amassed the works of the great dead in enormous qualities: Raphaels, a small Michelangelo marble, Correggios, Veroneses, Tintorettos, Guido Renis and —above all — multitudes by Titian, the king’s favourite painter (and who can blame him).

Some of these are brought back together in Burlington House. There are superb loans from the Prado and the Louvre, two museums where many of Charles’s prized possessions ended up, with Titian’s ‘Supper at Emmaus’ from Paris and from Madrid ‘Charles V with a Dog’ and ‘The Allocution of the Marquis de Vasto to his Troops’ standing out.

From the Gonzagas of Mantua, who were down on their luck, Charles extracted Mantegna’s multipart ‘Triumphs of Caesar’, currently filling the grandest gallery at the RA. Sections of the exhibition are devoted to the Mortlake tapestries — derived from the Raphael Cartoons that had been bought by the king — and to the small-scale works that filled his private cabinet room in Whitehall Palace. Two more rooms are filled with 16th-century Italian works. A selection of Charles’s ancient Roman and Greek sculptures — a less impressive collection than his modern art — are placed here and there.

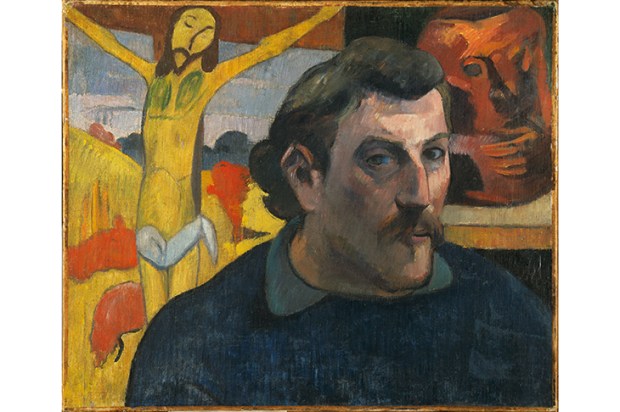

As you walk around, you get a sense of a personal taste — and a connoisseur’s eye. Just as his architect Inigo Jones set the pattern for Georgian building, Charles himself provided a model for country-house collections: Van Dyck portraits, Italianate opulence in the Venetian manner, a touch of Flemish baroque. He loved Rubens so much he kept the artist’s self-portrait in his bedroom.

He also owned a large number of northern European paintings by Holbein, Dürer and others — many gathered at the RA — but how much he valued these is debatable. At one point, he swapped an album of Holbein drawings for a Leonardo da Vinci (admittedly throwing in a work by his beloved Titian as well).

The King himself is at the exhibition’s heart. Its greatest coup — in a show that contains many — is the juxtaposition of Van Dyck’s three grandest portraits of him: here he is, coming at you from every direction. On one side the ‘Equestrian Portrait of Charles I’ from the National Gallery, his mount a preposterous beast with minuscule head and carefully coiffured mane. From another angle, the King rides through a triumphal arch amid swathes of fluttering drapery in a grand picture intended for St James’s Palace. Best of all is ‘Charles I at the Hunt’ from the Louvre. Was there ever a more romantically glamorous depiction of sovereignty? Hand on hip, wearing an enormous floppy hat and softly luxurious boots, Charles gazes down on us in a pensive yet lordly manner. Behind, his verdant realm stretches away towards the sea.

Van Dyck’s pictures of Charles are brilliant, beautiful lies: he made this tiny, less than competent man look powerful and imposing. We get an idea of what Charles actually looked like, when slightly younger, from Daniel Mytens’s full-length portrait of 1628. Mytens was a less gifted but, one guesses, more soberly accurate painter than Van Dyck. His Charles is a nervous-looking little fellow, too small for his smart clothes, with large nose and protruding eyes.

In British sovereigns there has tended to be an inverse relation between artistic taste and political nous. That other royal aesthete, George IV, almost brought the monarchy to an end. Charles actually did so — at least for a decade. The reason why his collection needs to be reassembled is that it was sold off by the Commonwealth government after his execution. And, playing Roundhead’s advocate for a moment, one can see why it might have niggled.

Rubens himself remarked that the English court was conspicuous for ostentatious display and debt. The consequence was corruption: ‘public and private interest are sold here for ready money’. Rubens’s own wonderful ‘Landscape with St George and the Dragon’ (1630–35) shows the king conquering the scaly monster of puritanism, bringing peace and prosperity to the nation.

The political reality proved otherwise. On 30 January 1649, by a dreadful irony, Charles stood briefly in the Banqueting House under Rubens’s ceiling — on which his father James I rises towards the heavens in baroque clouds and putti — before stepping outside on to the scaffold.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in