Last week, Peregbakumo Oyawerikumo, aka ‘The Master’, was finally caught and shot by the Nigerian army. Oyawerikumo and his Egbesu Boys had styled themselves as local Robin Hoods, taking riches from oil companies in the Niger Delta, but they won’t be much missed. In the remote swamp town of Enekorogha, their demise will be celebrated, because this was the scene of their most notorious crime.

It was here, last October, that the Egbesu Boys kidnapped Ian Squire, an optician from Surrey who was working at a clinic, and three fellow Britons: Cambridgeshire GP David Donovan and his wife Shirley, and optometrist Alanna Carson, from Northern Ireland.

On their first day in captivity, the Master’s men unexpectedly handed Mr Squire the acoustic guitar they had taken from his lodgings. Squire played ‘Amazing Grace’, which cheered his co-hostages, but apparently rattled one of the more trigger-happy gunmen, who fired in the group’s direction as a warning to quieten down. Mr Squire, 57, was hit and killed.

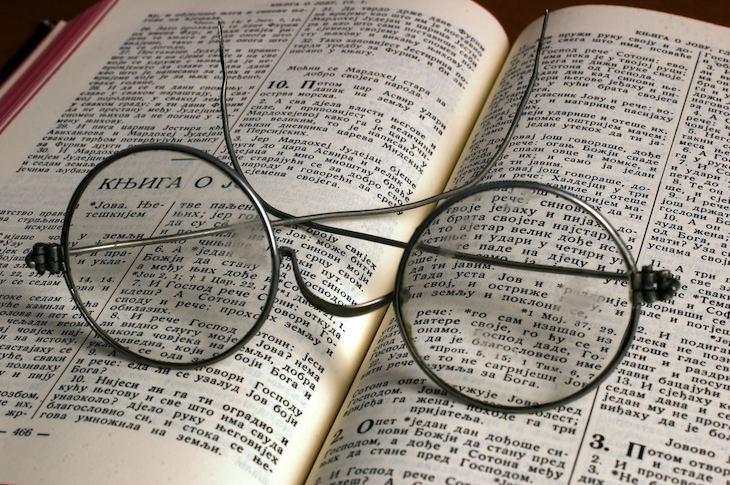

So ended the life of a man who had brought both courage and innovation to his charity work. Mr Squire had invented a solar-powered lens-grinding machine so that his eye clinic could make spectacles on the spot — a Vision Express for the developing world. It used glasses donated from lost property at Heathrow airport, not far from his high-street practice in the commuter town of Shepperton.

Squire and co. however, had not come to the lawless Delta region on behalf of some frontline aid agency such as Médecins Sans Frontières. Instead, they were foot soldiers of a less fashionable and largely forgotten wing of aid work — Christian missionaries.

I met the Donovans at their Cambridgeshire home late last year, not long after their release from their 22-day ordeal. They were keen to pay tribute to their fallen colleague, whose charity, Mission for Vision, had joined forces with the Donovans’ clinical charity, New Foundations. As the couple served up soup over their kitchen table, it struck me that these were people of a sort I’d never encountered in two decades reporting on Africa and the Middle East. Here were white Christian missionaries, talking unapologetically about God.

I’d assumed such a species was long extinct, deprived of habitat by a professional aid sector that is uncomfortable with anything so easily associated with Britain’s colonial past. I was wrong. According to Ray Porter, chairman of Global Connections, an association of evangelical mission agencies, there are ‘several thousand’ British missionaries working through various church organisations worldwide today.

True, Christian Aid, one of Britain’s biggest aid organisations, still counts itself as a faith-based outfit. The difference, though, is that Christian Aid wears its religious colours very lightly. When its press officers do ‘advocacy’ these days, it is more likely to be on climate change or ‘tax justice’. Evangelising, in other words, is fine — as long as it’s not about God. As David Donovan points out, in the increasingly liberal theology of the West, ‘the Gospel, ironically, is often the first casualty in Mission’.

‘Missionaries do suffer from a certain post-colonial legacy that says everything in Empire was bad,’ says Paul Thaxton, of the Church Mission Society, whose past missionary work includes drug rehab work in Pakistan and working with south London gangs. ‘But these days, we’re not there to “sort people out”, we’re there to work with them.’

Most of the unease about faith and aid work going hand-in-hand is a ‘particular expression of western secularism,’ adds Mr Thaxton’s colleague Colin Smith, the society’s Dean of Mission. ‘That unease is seldom shared by the communities where missionaries are working.’ Certainly, for the Donovans, an unshakeable faith was all but essential in Enekorogha, whose name translates roughly as ‘The Place You Cannot Stay’.

David suffered a previous kidnapping attempt in Enekorogha in 2009. Shirley once caught a potentially deadly form of malaria. They were robbed of their boats twice. Humidity destroyed most electrical equipment, and rats ate their walkie-talkies. Even the grizzled Scottish oil workers down the road in Port Harcourt thought they were mad. Had they been any regular NGO, their ‘risk assessment’ officer would probably have shut them down.

Dangerous as it was, though, the work that the Donovans and their companions did in Enekorogha made a difference. Prior to their arrival, the village had a child mortality rate of around 45 per cent. When measles and cholera cases spiked, as they did at certain times of year, the resultant infant death toll was known locally as ‘the harvest’.

The missionaries helped reduce mortality to around 2 per cent — a fact not lost on the local witch doctors, who had been hostile to the clinic when it first opened, but who ended up seeking treatment there themselves. The village idol keeper, a burly figure from whom local militants would ask for blessings, told the Donovans ‘the god you serve is greater than the god I serve’, and asked them round to read the Bible.

You might think ‘So what?’ But as Shirley points out, these days, fighting witchcraft isn’t such an obsolete cause. As Britain’s Anti-Slavery Commissioner has highlighted, witch doctors are sought out by Nigerian sex-trafficking gangs, who use the fear they inspire to terrify women into working as obedient sex slaves in British brothels. As a method of intimidation, it can be just as effective as deploying a violent pimp.

Indeed, the barbarities inflicted by superstition were something Shirley’s celebrated predecessor Mary Slessor had no truck with either. One practice she stamped out in Calabar was a tradition of killing newborn twins, on the basis that one or other sibling was always born evil. Such work was why, more than 80 years after her death from malarial fever, she became the first woman ever to appear on a Scottish banknote.

Whether her modern-day missionary successors will ever be similarly honoured remains to be seen. But in Enekorogha, where the Donovans’ clinic finally reopened again last week, locals have already named several newborn babies ‘Ian’ in memory of the late Mr Squire.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in