Has a more beautiful machine in all of mankind’s fretful material endeavours ever been made than a ’60 Ferrari 250 Granturismo? Go to the Design Museum and decide.

I have driven many Ferraris and the experience is always unique. They are alive, demanding, feral, sometimes even violent or truculent. Addictive, too. Once, in Haverfordwest, I arrived sweating and puffing after seven hours in traffic. I parked the 246 GT at the hotel for a moment but then, unable to ignore the hot, seductive car, I got back in and drove up and down the coast road; up and down, up and down. Just because it was there.

Kierkegaard thought that ‘the best demonstration of the wretchedness of life is obtained through a consideration of its glory’. Thus, the motor car. Heavy, expensive, wasteful, dangerous, but romantic too. The car is the ultimate analogue experience: the laws of nature made explicit with explosions and exhausts, forces and fears, sculpted metal. And Ferrari is the ultimate car: a machine-for-driving-in conceived and executed without compromise.

But in this year of its 70th birthday, London, Paris and Oxford have announced plans to ban cars — or at least the oil-burning sort. As petrol cedes to electricity and brute analogue certainties cede to epicene digital abstractions, as driving becomes a gruelling chore, the Design Museum’s Ferrari exhibition has an elegiac quality. Or it might have had, if executed a little differently.

What is Ferrari? One answer is: a symbol of Italy’s post-war ricostruzione. The Vespa scooter and Fiat Cinquecento had similar roles, but were democratic forms of transport to mobilise peasants, women and priests. Ferrari was different: lordly and magnificently detached from the mundane, but nonetheless a superb demonstration of Italy’s established national genius in craft and art. The part of Emilia-Romagna that Ferrari calls home has metal-bashing traditions going back to the Etruscans. Indeed, the name ‘Ferrari’ approximately means ‘smith’.

Another answer is that the Ferrari story is a heroic adventure by an individual of singular, even sadistic, will. This was Enzo Ferrari, born in Modena in 1898. He finished fourth in his first motor race, a hill climb at Poggio di Berceto near Parma. Soon he was managing the Alfa Romeo racing team under the auspices of Scuderia Ferrari and the marque of this stable was the cavallino rampante (prancing horse) that Ferrari had slyly lifted from a first world war fighter ace. When Alfa Romeo frustrated his ambitions for a new car, he decided to build his own.

At the Ferrari factory in Maranello, they point out the five windows by the factory gate that meant the old man could keep constant interfering watch on the traffic. ‘I am not a designer,’ Ferrari once said, ‘but an agitator of men.’ Indeed, he was. He agitated widely. The mystique of Enzo Ferrari — remote, obstinate, forbidding, unsentimental, determined, manipulative — contributed powerfully to the mystique of the cars. Do machines have life? Of course they do.

Competition obsessed him. ‘I have no interest in life outside racing cars,’ he confessed. His love was machinery, not people. Remote? The racing driver Eugenio Castellotti explained that he was only allowed to meet Enzo himself after buying no fewer than seven of his racing cars. And so many racing drivers were killed in Ferraris that the Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper, damned Ferrari as a ‘Saturn’ for destroying his children.

But these victims were always willing. From the beginning, clients were important. Two of the most famous were Roberto Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman. They well understood how Eros and Thanatos competed in motor racing. Bergman reconciled herself to Rossellini’s dangerous need for speed when she wrote: ‘Forbidden things are always so desirable.’ To this end, Rossellini gave Bergman a Ferrari as an anniversary present. She called it ‘Growling Baby’. They took delivery in Rome and drove it to Stockholm’s Grand Hotel in her native Sweden.

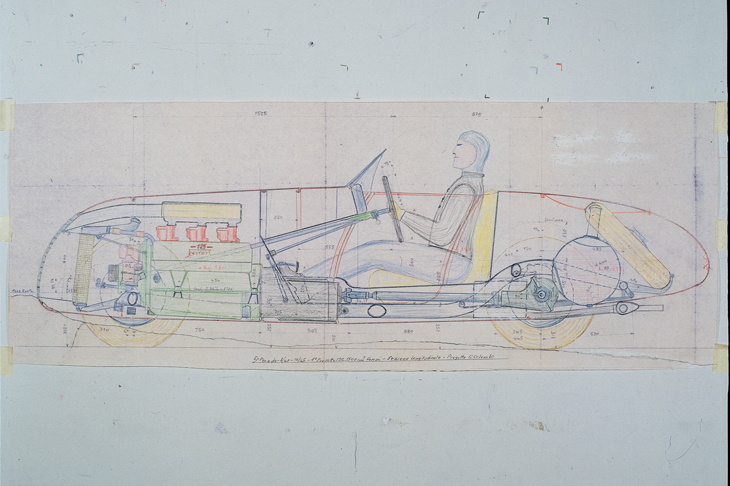

Crucial to the Ferrari story is the relationship with Pininfarina, one of the great carrozzerie, or coachbuilders, of Turin. The collaboration began in 1951 when Ferrari realised that his racing cars had to be consumerised for the public in order to pay for his racing through retail sales. A 2.6-litre 212 was shown at the Brussels Salon de l’Automobile in 1951. ‘It gave,’ according to one observer, ‘the youth of the day something to dream about.’ Exactly so.

This collaboration made metal sing. Until the 1973 Daytona, the first Ferrari manufactured in large numbers, almost every Ferrari was, sculpturally speaking, a reproduction of a Pininfarina idea: metal bashed over wooden formers by his henchman Sergio Scaglietti, following an original disegno, but each panel slightly different from its predecessor. Nowadays, Pininfarina has been sidelined and Ferrari design has been taken in-house under the charge of Flavio Manzoni who, in that curious way of the motor industry, once worked for proletarian Volkswagen and designed the very fine, but modest, Polo.

The design of this birthday exhibition, essentially a reinstallation of one floor of the Ferrari Museum in Maranello, is by Patricia Urquiola, a fashionable Milanese architect. There are superlative cars on display: an ’87 replica of the very first 1947125 S and that very same ’73 365 GTB 4 Daytona, the first Ferrari to be productionised. But there is also a cabinet of curios from the collection of Ronald Stern, including Enzo’s own driving licence and the tragic Mike Hawthorn’s helmet. Britain’s first world champion drove a Ferrari. This confirms, if confirmation were needed, the occultish, juju element of Ferrari worship. Like many aesthetic adventures, like religion, Ferrari is beyond rationality.

Emilia is the centre of Italian food production: Parma ham and Parmesan cheese are headquartered up the road from Ferrari. So suffused is the region with ideas about food that Flavio Manzoni calls his design studio a ‘cucina’. Indeed, he says that his latest car is a composition as dense as an egg, with shell and contents all indivisible. As if to prove a point about gastronomic connections, this latest car, the gorblimey LaFerrari Aperta on display in the Design Museum, belongs to Gordon Ramsay. But in egg terms the exhibition is a little underdone.

It is a delicious visual treat, but superficial rather than analytical, no matter what the ‘under the skin’ subtitle promises. On a recent visit to Maranello, Manzoni, an architect, told me: ‘We follow the function, but we are artistic, sculptural and beautiful.’ Despite or because of the glories on display, the mystery of beauty remains intact. Perhaps as it should.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in