Everyone knows — don’t they? — that the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain is the UK’s youngest world-class symphony orchestra — an ensemble of musicians aged 18 and under that’s the equal of any professional band (and better than some). But it’s also the largest, and we don’t hear enough about the sheer sonic impact of hearing 157 musicians moving with absolute precision. Even the smallest gesture by an 87-player string section has a sort of heft, a physical weight and depth that you can sense in the air around you. Overwhelming when the whole orchestra is playing at full power, it’s even more tangible in quiet passages, as if you’re in the vicinity of some vast, invisible living creature.

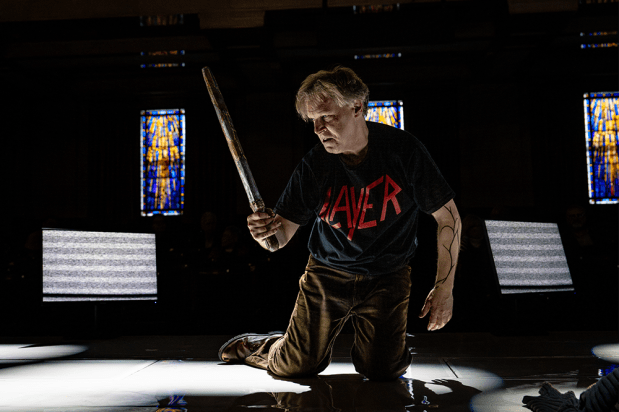

It was a neat idea, then, for director Daisy Evans to make the orchestra into a character in the NYO’s concert staging of Bartok’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, namely the massive, semi-sentient presence of the Castle itself. The stage directions ask for it to give ‘a cavernous sigh, like night winds’, so Evans had the orchestra’s members produce the sound themselves, with hands over mouths. Neon cables snaked between the players’ chairs, glowing blue for tears, yellow for gold or red for blood. Robert Hayward as Bluebeard repeatedly turned and surveyed the immense forces behind him, shoulders slumping, and when the Third Door revealed his treasure-chamber, players lifted their instruments up to glint and sparkle in the coloured light. The surtitles were accompanied by drawings of doors by Chris Riddell, and unnamed members of the National Youth Theatre enthusiastically declaimed the opera’s spoken prologue.

It looked striking, as far as it went. With Rinat Shaham standing in as Judith at short notice, and (perfectly understandably) singing from a music stand while Hayward performed entirely in character, you had to wonder if the original intention hadn’t been to go quite a bit further. What we got, though, was potent. Hayward is tremendous in this role: a noble ruin of a human soul, whose ringing, deeply expressive declamation is undercut by the different gradations of pain that move across his face. He can make himself look as if he’s aged two decades within a single bar of music. Shaham’s Judith was subtler and less fierce than some — not afraid to let her voice curdle as she turns the screws on her spouse, but occasionally underpowered against the sheer splendour of the orchestral sound.

That sound, of course, was the point of the evening. You just knew that when the fifth door opened, Sir Mark Elder and the NYO would make the floor shake, and Elder’s pacing of the opera’s single-act arc was both spacious and urgent. Still, it was the quieter details — world-weary clarinet and horn solos, quivering surges from the cellos, and the stunned fragility of those massed violins in the closing bars — that gave this performance its fever-dream immediacy, and showed you how profoundly Bartok’s score had got under the skin of these teenage artists. As well it might.

Meanwhile at Covent Garden, the Royal Opera played out the festive season with David McVicar’s 2001 production of Verdi’s Rigoletto. Superficially, at least, you can see the logic of Rigoletto as a Christmas show: a juicy, handsomely dressed helping of Victorian melodrama, stuffed with hummable tunes. But any staging that takes Verdi’s tragedy at anything like face value is going to leave an extremely nasty aftertaste, and to his credit McVicar does nothing to sugar that. Apparently the revival director Justin Way has toned down the opening orgy at the Duke of Mantua’s court, but the sight of courtiers in gorgeous Renaissance costumes grimly dry-humping each other in the background as the Duke (Michael Fabiano) reels out his ‘Questa o quella’ certainly soured the mood pretty effectively.

The darkness of this production is its most striking feature. Michael Vale’s grungy sets concentrate the drama powerfully and conductor Alexander Joel has a sharp ear for Verdi’s gamier orchestral colours. In that setting, the soft-edged glow of Lucy Crowe’s singing as Gilda stood out with intense sweetness. Andrea Mastroni’s Sparafucile had a tone like bitumen; a brooding, Fate-like figure whose monumental presence could perhaps have given the drama the resonance of Greek tragedy had the production overall been a bit more tightly focused. As Rigoletto, Dimitri Platanias was more alluring and charismatic — vocally at least — than the Duke: Fabiano had power, but sounded as though his voice needed a good rest. On this first weekend in January they all went at it with vigour, without really dispelling the feeling (Crowe and Mastroni apart) that they were performing their parts rather than connecting dramatically. Woolly ensemble from the chorus and interminable scene changes reinforced a distinct end-of-the-holidays feeling. It seemed to be doing a roaring trade, anyway.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in