The impermanence of works of art is a worry for curators though not usually for artists, especially not at the start of their careers. But Anthony McCall was only in his mid-thirties when his creations vanished before his eyes.

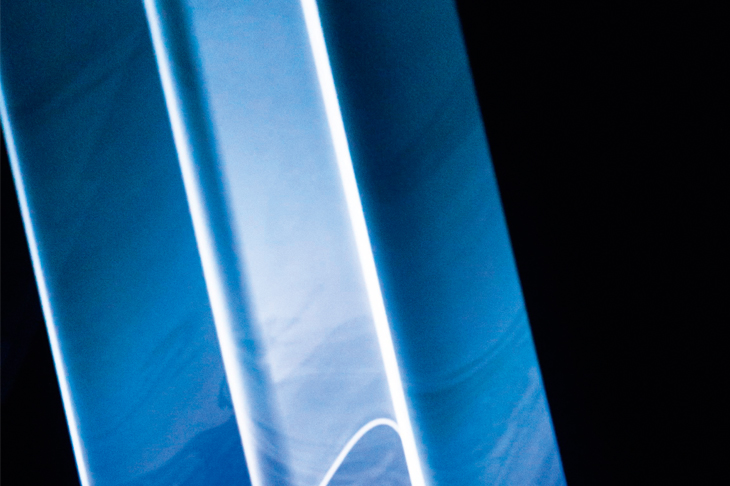

It was in New York in the early 1970s that McCall came up with the idea of ‘solid light works’, animated projections of simple abstract shapes in which the beams of projected light assumed a physical presence. Not being taken seriously by commercial galleries — ‘It did occur to me that I hadn’t made a terribly wise career decision’ — McCall’s solid light works were initially shown in the sorts of dusty, smoky downtown lofts where devotees of ‘expanded cinema’ gathered. Then, just as they began to attract attention from public institutions, their solidity crumbled. In the dust- and smoke-free zones of the modern art gallery the sculptural beams of light became invisible: from dust they came, and without dust they went.

Fortunately the British-born artist had another string to his bow, having initially trained at Ravensbourne college in graphic design. From the early 1980s he reinvented himself as a designer of art books and catalogues, a career change so thorough that people thought there must be two Anthony McCalls, and he almost began to think so himself. Then the haze machine came along to solve the problem that had put a halt to his fine-art career, and by the time he returned to the art world in the early noughties it was ready for his work.

His new exhibition, Solid Light Works, at the Hepworth Wakefield — his first in Britain for ten years — includes the work that marked his return, appropriately titled ‘Doubling Back’ (2003). The effect is magical. Viewed from the outside, the slowly moving beam of light appears to be contained by a gauzy membrane that gilds your hand if you penetrate its surface; step through the membrane and you enter another dimension, an ethereal atmosphere of swirling vapour where you can imagine yourself seated on the clouds of heaven looking down a shaft of celestial light. Actually, the darkened gallery with its carpeted floors has the feel of a movie theatre rather than a church. McCall likes ‘the little nod to cinema’ — lucky there are no usherettes with competing torch beams.

The Hepworth’s ceilings are not quite high enough to accommodate McCall’s newer vertical projections, which require ten metres of headroom. Large as this sounds, all the solid light works, whether vertical, horizontal or, most recently, diagonal, take man as their measure: ‘“The Vitruvian Man”,’ he says, ‘is carefully placed in the centre of the beam.’ Turbine Hall folie de grandeur is not for him: ‘If I were asked to make a piece twice as big, I’d say no, it’s not going to work — the body would lose its reference.’ The human figures are part of the work, caught in the nets of light like shadow puppets.

Part film, part drawing, part sculpture, McCall’s shape-shifting creations defy categorisation. Using the same basic vocabulary of straight lines, ellipses and waves — ‘I haven’t added to them much’ — they might today be called ‘projected installations’, though McCall prefers the less pretentious word ‘film’ with its connotation of sequential development and its connection with performance. It was the need to record one of his early fire performances that originally prompted him to turn his hand to film. His first attempt in the medium, ‘Landscape for Fire’ (1972), shows a grid of petrol drums dotted across a disused Essex airfield being set alight by a team of white-overalled performers. With its soundtrack of howling wind and distant foghorns punctuated by the fizz and thunk of lit matches being thrown into the drums, it seems dramatic enough, but to its maker the resultant film felt like a second-hand experience of an event belonging to another time and place: ‘I thought it might be possible to make a film that only existed in the present and shared space with its audience. I became interested in the idea of real time.’ Back in New York, after adding animation to his skill set — ‘When you need to find something out, you find someone to teach you’ — he produced his first solid light work, ‘Line Describing a Cone’ (1973).

What struck me, watching the film of the fire performance, was the paradoxical efficiency of the operation with its uniformed marshals patrolling the regimented rows of flaming drums. McCall likes paradoxes. Part of the fascination of his solid light works lies in the tension between the rigour of their design and the volatility of their materials. Captivated by ‘the beauty of something shifting and changing in a way that you can control and be part of’, he delights in containing the uncontainable.

Knowing that he has also made works involving water and earth, I’m tempted to read all sorts of metaphysical meanings into his allusions to the four elements, which he refuses to confirm — such meanings, he says, ‘are the work of the spectator; they belong to the art of looking, not the art of making’. He recognises, though, that a narrative element has crept into the titles of works such as ‘Face to Face’ (2013), in which two of the animated drawings he calls ‘footprints’ are projected on to facing screens. Another double projection, ‘Leaving (With Two-Minute Silence)’ (2009), is a self-confessed ‘meditation on mortality’ in which one elliptical form grows as another dwindles. ‘Leaving’ is the first of the solid light works to have a soundtrack — or ‘sound shroud’, as he calls it — of distant traffic and harbour noises, including foghorns. ‘I urgently needed a two-minute silence and the only way to create silence is to have sound you can then remove,’ he explains. ‘When it does go silent, it’s a deafening silence.’

Luminously simple as these works seem, the choreography they involve is astonishingly complex, as testified by the accompanying mini-retrospective of works on paper ranging from volumetric sketches, sequential drawings and animation schemas to ten years’ worth of notebooks: ‘This is where everything begins — all the rubbish goes in there.’ The rubbish is the residue of a creative journey that has taken McCall from dusty loft to spotless art gallery via a 20-year cooling-off period in the design studio. As someone whose fine-art career was almost ended by the white cube, does he feel that the contemporary art world could be getting too clean for creativity? No. ‘Creativity is by definition opportunistic and gets round problems. Some new form of art may emerge which finds those boxes irrelevant. Art plays tricks on us all. Just when we’re thinking: “This can’t get any worse,” something glorious happens unexpectedly.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in