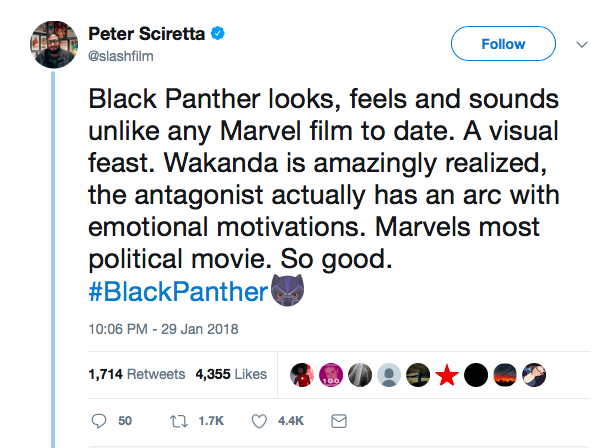

Black Panther opened in Australian cinemas recently and it certainly does not disappoint. It’s the eighteenth movie of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, a franchise that over the past ten years has made $13.5 billion globally at the box office. Make no mistake though; this is not just an action-packed adaptation of the original comic book. With a budget of $200 million, this is also the slickest presentation of progressive politics that you are likely to witness this year. As Peter Sciretta, editor of Slash Film, tweeted:

But first, for all those who have no idea Wha-the-Vibranium I am talking about, here’s a quick synopsis (don’t worry, no spoilers).

But first, for all those who have no idea Wha-the-Vibranium I am talking about, here’s a quick synopsis (don’t worry, no spoilers).

The Black Panther comic was first published in 1966, just a few months before The Black Panther Party – a violent civil rights political movement – began. So, it’s not by accident that the movie’s opening and closing scenes are set in Oakland, California, bookending the entire movie, the very place where The Black Panther Party was established. (According to The Washington Post: “To avoid controversy, Marvel briefly changed the name to Black Leopard but later realized that just didn’t have the same oomph.”)

What’s more, the year is said to be 1992. The same year as the Los Angeles (Rodney King) race riots. All of which is to say, as Nick Bhasin explains:

Black Panther arrives in the middle of this heavily mined, fracked and plundered story landscape, led by an action-packed trailer featuring Gil Scott-Heron’s seminal 1970 black power anthem, ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’. The message is clear: You may have seen superhero movies before, but this is serious. This is political.

Significantly, the film’s African-American director and co-writer, Ryan Coogler, was born and raised in Oakland. What’s more, the entire cast is black, with the exception of Andy Serkis and Martin Freeman. Since both of them also appeared in The Lord of the Rings (Gollum and Bilbo Baggins) they are now being referred to as, the “Tolkien white guys”.

The overarching framework of the movie then is that of, “Afrofuturism” – something Steven W. Thrasher describes as “a black perspective on the politics, aesthetics and cultural aspects of science, science fiction and technology.” Similar to Thor Ragnarok, there is also a strong anti-colonialist message.

It’s little wonder then that The Guardian refers to Black Panther as “Afrofuturistic gold”, and not surprisingly, suggests that it could also be the answer to our own indigenous and African youth problems. Which is especially pertinent given the current context of the “Black Lives Matter” movement sweeping across the United States. As Jamil Smith from Time states:

What does it mean to see this film, a vision of unmitigated black excellence, in a moment when the Commander in Chief reportedly, in a recent meeting, dismissed the 54 nations of Africa as “sh-thole countries”?

But with that said, the political solutions that Black Panther offers are shallow and disappointing. Even Steven Thrasher, a social progressive who writes for Esquire, concluded that: “Black Panther’s Political Message was too Conservative for its Revolutionary Title.” Because the problem with Black Panther is that it just isn’t black enough, and the political solutions that it offers the audience are “grey”, to say the least. As Ben Shapiro explains:

T’Challa’s alternative is essentially the Democratic Party platform: spending lots of money in inner-city Oakland, as though that hasn’t been tried. One of the great ironies of the film is that a throwaway laugh line actually tells a story the film isn’t willing to contemplate: when a Wakandan ship decloaks and lands in Oakland, one of the kids immediately begins thinking about how to disassemble it for parts. The audience laughs – but it’s that attitude that has cursed Oakland in real life, not simple material privation. That’s why Democrats can throw trillions at the War on Poverty and end up achieving nearly nothing.

As so often, Shapiro’s observation is witty and correct. But the problems are even deeper. Let me suggest that there are at least three.

First, sexism. Black Panther is being universally lauded for its championing of gender politics. Every major role—except the Wakadian King—is filled by a woman. But while the film more than passes the Bechdel Test, (so much so in fact, that they are presented as being more male than female) sadly, the only black American woman in the movie is given short shrift. As Christopher Lebron, from The Boston Review, writes:

The character, Tilda Johnson, a.k.a. the villain Nightshade, has, by my count, less than fifteen words to say in the movie… She is also invisible and nearly silent. In the comic books, her character is both a genius and alive and well.

This point is all the more pertinent when you realise that the kingdom of Wakanda is founded upon a patriarchal monarchy! As Steven Thrasher laments, “What is a more colonialist ideology than upholding the divine right of kings?”

Second, racism. It’s indeed strange that in a movie devoted to “black supremacy” the plot hinges not upon the defeat of Ulysses Klaue (one of the main bad guys with a distinct South African accent) but the character Killmonger, who’s an African-American. As Lebron rightly points out:

A contest between T’Challa and Killmonger that can only be read one way: in a world marked by racism, a man of African nobility must fight his own blood relative whose goal is the global liberation of blacks. In a fight that takes a shocking turn, T’Challa lands a fatal blow to Killmonger, lodging a spear in his chest. As the movie uplifts the African noble at the expense of the black American man, every crass principle of modern black respectability politics is upheld.

Third, Afrofuturism. Ultimately, the underlying premise of Black Panther, that African-Americans can only be liberated through the benevolence of their indigenous forbears, is flawed. But the myth of Afrofuturism is just that. It’s a myth! In a brilliant essay for The Atlantic, Vann R. Newkirk writes:

There is, of course, no Wakanda, no vibranium, and no (useful) cat-cowled superhero in the real world. Even among many of the most elite enclaves of blackness today, power is uniquely vulnerable and fragile, and there are as of yet no suits of any cost that will stop black youth from the ravages of police brutality the world over.

Clearly, Black Panther is a movie with a message. Everything from the iconic “Twin Towers” at the centre of Wakanda, to the closing scene where King T’Challa sanctimoniously lectures the United Nations that: “The wise build bridges, while the foolish build barriers.” It made me wonder – for a movie that is so overtly politically, why didn’t he just say “the foolish build walls”? Or would that have been just too obvious, and miss out on the use of alliteration…?

In the end, when the house lights come on, the popcorn has settled, and you’ve sat through the not one, but two, extra scenes hidden amongst the credits, John Nolte, from Breitbart, has the best insight of all. Provocatively, Nolte’s conclusion is that the underlying message is this: “The hero is Trump, the villain is Black Lives Matter.”

Mark Powell is the Associate Pastor of Cornerstone Presbyterian Church, Strathfield.

Illustration: Luke Powell

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in